On Sunday, I have a very pleasant day taking in mediocre art across a variety of disciplines — sculpture, photography, improv theater, film. The art is all over the city, and, in the gaps in between, there is ample opportunity for edifying conversations on what exactly bad art is and where it comes from.

The first show I see is a street photographer from the ‘70s having his work exhibited in a trendy gallery in Hudson Yards. The photographs themselves are fine, kind of gritty, a bit performative, but it looks like they have been captured by the gallery surrounding them. And that work isn’t just mediocre or bad: it’s disgusting. My gallery-goer companion and I have the exact same reaction, and it takes a bit of work — as soon as we’ve beaten our retreat from there — to figure out why we so strongly feel that way.

Everybody has a right to express themselves: that’s my belief. And so, at some level, the work here isn’t doing any harm. It is a form of expression. And it doesn’t particularly bother me that the gallery is also blatantly commercial. I also believe that everybody has a right to earn a living — and why shouldn’t they be able to do that through selling art?

But neither of us buy that. The problem with the work at this gallery is that it is a lie — and we both feel that right away. Its whole purpose is clearly to sell — the giant “All Art For Sale” at the entrance makes that evident — and the ‘art’ just a means to an end. The art itself, the photographs aside, is deeply derivative Pop Art — dollar bills wedged into a popcorn bag, pictures of Mickey Mouse. It’s supposed to belong to a ‘conversation’ — American art as passed down from Warhol and Basquiat. The placards all sound really good — the artists are impeccably credentialed, seem hip, their work is really being sold for a lot — but it’s also clear that no effort, no originality at all, went into it.

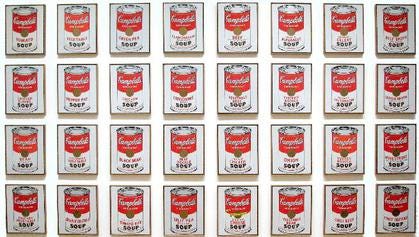

Playing devil’s advocate, my gallery-goer companion says, well, how is it different from the original Pop Art? This is a tricky question, since all of Pop Art might well be bullshit — and a lot of people thought so at the time of the first exhibitions. But, trying to respond to that, I say that Pop Art does respond to something real. We are living in a world of copies, duplication, etc. That does cause a certain amount of psychic distress. For Warhol to put up his first images of Campbell’s Soup, some pain and some courage had to go into it. What he was saying, in effect, is that he knows that his work is ‘ugly,’ that it doesn’t do what ‘art’ is supposed to do, but it is reflective of the world he is in, and does express a certain existential pain he has, and therefore is worthy of being shown. And viewers do feel some power in that — which connects directly back to the courage and the conviction that Warhol had.

The work in the Hudson Yards gallery looks very much like Warhol’s did, which of course looked very much like cans of tomato soup, but the derivativeness of the Hudson Yards work is a tip-off — that no real courage, no real individuality went into it. Well, but how can you tell what’s sincerely felt and what’s not? says my gallery-going companion.

Which is a hard question. The response is that nobody really can. That’s why art criticism exists, that’s why people can have these sorts of arguments until the end of time. But my conviction is that it’s not just a matter of interpretation. Originality and risk always tell you something — they give you some of the feeling that the artist had when they were making the work; ideally, you feel something very similar to the charge that they had. If somebody does derivative work, and especially does it in a highly derivative, easy-to-fake-it genre like Pop Art, it becomes almost impossible to feel what they felt or anything close to it. The work just becomes a cunning vehicle for imitating art and achieving its function as a high-end commodity. It’s not really that some other beholder might see something different in it. The lie is intrinsic; the slick commercialness, the derivativeness, the safety of the work, all give it away.

***

There’s a photography show by a young artist, a friend of a friend, on the Lower East Side. This art is also not great, but the two of us have a very different kind of response to it. The artist — ‘Tim’ — is clearly expressing something. The work is pictures of himself on a trip to the South, and he’s clearly grappling with being a black person in this part of the country. There are photos of him with his face obscured, there are a series of photos of him walking in a circle, with him in varying degrees of visibility, there are photos in which he strikes a sort of heroic pose but with his head bent out of the way of the shot. There are also photos of flowers from the region and newspaper clippings from the Civil War era.

The feeling — and, again, my gallery-going-companion and I are in alignment — is that we like Tim, we feel that he is expressing something of himself and his relationship to race, but, really, we’re not getting that much of him. Some of the photos are very mannered — particularly when he strikes the heroic pose. The flowers and the newspaper clippings don’t really tell us very much. The sense is that he’s doing what he’s supposed to be doing, he’s being a good kid, but maybe doesn’t know himself that well or isn’t expressing all that much of himself.

***

The theater show is a bit different. It’s a mother and daughter walking around the stage in circles reciting events from each of their lives. It’s an interesting format, interesting to see a mother and daughter sharing difficult truths with one another, and we really end up knowing a lot about them by the end of the performance, but, at the same time it’s deeply frustrating. Neither seems willing to risk or to challenge each other. At one point the daughter says something like, “And I thought I was never good enough for you.” To which the audience is suddenly alert, waiting for the mother to respond, argue or apologize or something, but, instead, when it’s her turn, she talks about Trump.

My theater companion and I are both oddly angry as we leave. It is brave what the two of them are doing, sharing their relationship in front of an audience like that, but something pulls them up short. It really isn’t easy to talk to a parent or child in that sort of setting, and, understandably enough, they find themselves in patterns of avoidance, with politics as a major crutch. We end up knowing a lot about the two of them — what they like to read and watch, how old each of them was when they lost their virginity or first tried drugs — but somehow we don’t know anything essential, we don’t know, for instance, how the mother would respond if the daughter told her that she’d always felt disapproved of.

***

The capstone to the day is a Hungarian movie from the ‘80s about a man and a woman, he very vain, she very libidinous, and how they pass through 19th and 20th century history together (neither of them ever aging). It’s long and slow and, I’m convinced, not very good. Her boyfriends keep getting introduced and then dropped and then, out of nowhere, resurfacing again. The acting and writing are often campy. But, afterwards, through a long conversation and some internet scouring, I’m talked into it. The movie isn’t very logical in any of the ways that I would recognize logic: the characters don’t serve as separate centers of gravity with unique intelligences. But there is a logic to it that has to do with this very bizarre interplay between camera techniques and Hungarian history. “It’s the most complicated movie I’ve ever seen,” says one online reviewer, and I can see what he means. It’s still not really my taste — the leaps in logic are tough for me to take — but it falls into the category where different people can viably have different perspectives on it. It does have confidence and clearly has both sincerity and originality. Whether it ‘works’ or not is a separate and, in a sense, less-important question.

The reflection from the film is that there are so many ways to make good art. It’s possible for a film to have little discernible logic, risible acting and writing, and to still have so much in it. It’s possible for a mother and daughter, walking around a stage, with no budget, no plot, etc, to be captivating. In a way, it seems impossible that anyone could miss. And yet, people do miss, so badly, all the time. The reflection from the day of mediocre art is that the reasons people miss have very little to do with technique; and everything to do with holding back, being avoidant, lying to themselves.

If you speak your truth, it may not follow that the work becomes ‘good,’ but at least it becomes interesting. And, in the great ocean of mediocre art, interesting and truthful really should be more than enough.

Sam Kahn writes

.

There really is a discernible difference when art comes from a "real" place. I even notice this with text messages I send. Say I text someone "I love you" at a time I'm acutely feeling it: it lands different than if I text while I'm lying to myself or otherwise not connected to the words I'm writing. The person on the receiving end shouldn't be able to perceive that, and yet.

I've been to a few photography exhibitions in trendy Parisian galleries over the past few weeks and even just writing those words belies the problem with so much of "popular" art these days: so much of it seems to be about the image and the striving to *appear* to be something more than the sum of the parts. Which makes it extremely depressing (this is why "Triangle of Sadness" is such an important commentary on this age).

Thanks for a fantastic essay that opens up a neverending dialogue about why it's so often the wealthy who end up dictating what is considered worthwhile. They're wrong, of course-this is when the occasional Warhol or Basquiat come along and break through the veneer talking about something real--but this inevitably brings up the question of the danger of commercial success for an artist in an era when celebrity is valued over humble quietness, which is exactly what Warhol was speaking out against, and surely part of why Basquiat never made it to thirty ... and boy oh boy, do we ever now have our fifteen minutes of fleeting fame.