Extraordinary Machine

the literary determination of technology

Last week, the science-fiction magazine Clarkesworld closed submissions after the editor found himself swamped with stories written in whole or part by generative AI. Clarkesworld editor Neil Clarke told the Financial Times,

“Five days ago, the chart we shared showed nearly 350 of these submissions. Today, it crossed 500. Fifty of them just today, before we closed submissions so we can focus on the legit stories,” he said on Monday.

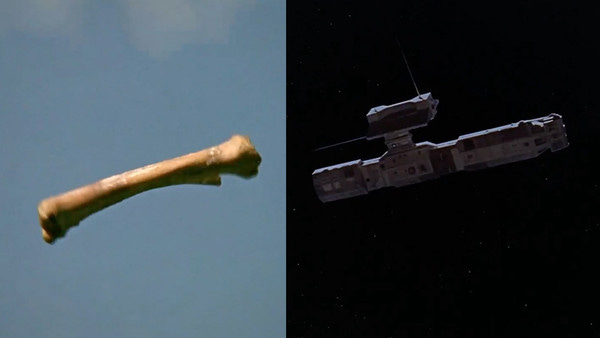

The magazine takes its name from legendary 20th-century science-fiction author Arthur C. Clarke. Clarke remains best-known to the general public as the co-author of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film whose famous match-cut between an early hominid’s hurled bone-club and a spaceship in orbit condensed into one indelible image-sequence humanity and technology’s co-evolution.

When a correspondent sent me the Financial Times article about Clarkesworld, however, I recalled from my science-fiction-reading youth one of Clarke’s most notable short stories, “The Nine Billion Names of God.” The 1953 tale is so brief as to be a fable, a joke, or both, with its famous last sentence serving as both moral and punchline.

In the story, a Tibetan lama hires an American corporation to provide sophisticated computer equipment for his lamasery high in the Himalayas. The lama explains his purpose to the skeptical executive. The monks have calculated that God has nine billion possible names; for three centuries, they have transcribed these letter combinations by hand, but, if aided by computer technology, they will be able to finish the project in three years.

“Luckily it will be a simple matter to adapt your automatic sequence computer for this work, since once it has been programmed properly it will permute each letter in turn and print the result. What would have taken us fifteen thousand years it will be able to do in a thousand days.”

The executive agrees and sends two engineers to the lamasery. The engineers grow dismayed, however, when they learn that the monks believe the world will end when the nine billion names of God have been calculated and printed, as one programmer explains to the other:

“Well, they believe that when they have listed all His names—and they reckon that there are about nine billion of them—God’s purpose will have been achieved. The human race will have vanished what it was created to do, and there won’t be any point in carrying on. Indeed, the very idea is something like blasphemy.”

Fearing the monks will turn on them when the computations are complete and the world doesn’t end, the engineers flee over the Himalayas before the computer completes its task, cracking jokes all the while about the immemorial folly of doomsday preachers.

Then, at the very moment the engineers know the computer in the lamasery behind them will have finished its enumeration of all God’s names, they look up to the sky. In the story’s oft-quoted final sentence: “Overhead, without any fuss, the stars were going out.”

As in 2001’s juxtaposition of bone-club and spaceship, Clarke again identifies the potential for the most advanced technology to abet and even to fulfill the most primal, archaic human impulses, whether we want to wage war on one another or to worship divinity and hasten its coming. But Clarke’s brief fable holds a more specific moral, one standing at the crossroads of writing and artificial intelligence. In the story’s implied theology, God has tasked human intelligence with the job of converting the creation into text.

Here pulp science fiction joins hands with the avant-garde, which held the conviction that, to quote Mallarmé, “everything in the world exists in order to end up as a book.” To complete this total conversion of world to text is in effect to solve God’s puzzle, to beat God’s game, after which human intelligence can be judged to have served its purpose.

If the story’s God objects to humans using their intelligence to design machines able to speed up the process of discovering every possible permutation of world-text, He would not put the stars out. Clarke, we can surmise, might therefore approve of his namesake magazine being made the plaything of artificial intelligence.

In fact, technological developments have long helped to transform literary creation without apocalyptic consequences. Two of the first major writers to use a typewriter, for example, were Mark Twain and Friedrich Nietzsche. As much as any other novelist, Twain turned fictional prose away from the highly rhetorical Latinate sentences that often flowed from the fountain pens even of writers as otherwise interested in demotic talk and hard fact as Melville and Dickens. Here is David Copperfield in a storm, the tempest muffled by all the subordinate clauses:

The tremendous sea itself, when I could find sufficient pause to look at it, in the agitation of the blinding wind, the flying stones and sand, and the awful noise, confounded me. As the high watery walls came rolling in, and, at their highest, tumbled into surf, they looked as if the least would engulf the town. As the receding wave swept back with a hoarse roar, it seemed to scoop out deep caves in the beach, as if its purpose were to undermine the earth.

And here is Huckleberry Finn in a similar storm, raining down swift and vivid colloquial sentences loosely strung together with ands and thats and semicolons:

Directly it begun to rain, and it rained like all fury, too, and I never see the wind blow so. It was one of these regular summer storms. It would get so dark that it looked all blue-black outside, and lovely; and the rain would thrash along by so thick that the trees off a little ways looked dim and spider-webby; and here would come a blast of wind that would bend the trees down and turn up the pale underside of the leaves…

The standard of prose after Twain becomes pointillist precision in the reportage of fact and speech, not attempts at lofty eloquence from the inkwell. Nietzsche likewise shoved philosophy away from the elaborate construction of metaphysical systems and toward the ironic aphorist’s short, sharp raids on skewed and always provisional truths. Their successors, whether Hemingway in fiction or Wittgenstein in philosophy, carried these typewritten styles to revolutionary extremes of minimalism.

To attribute such vast changes in the forms of fiction and philosophy to the typewriter alone would be to carry technological determinism too far, especially since Nietzsche in particularly didn’t use his early typewriter very extensively, but surely the conjunction is suggestive, useful as myth. Modernism’s most distinguished mid-20th-century exegete, Hugh Kenner, for example, often stressed the role of the typewriter in altering modern poetry and prose.

Not coincidentally, Kenner’s mentor was famed media theorist Marshall McLuhan, who summed up his own theory in an aphorism almost designed to be bashed out loudly with metal rods on paper flattened against a black platen: “The medium is the message.” In other words, whatever particular ideas or stories or values writers, artists, and thinkers wish to convey will be overtaken by the implicit worldview of their medium itself, whether handwritten prose’s tendency toward complexity and flow or typewritten prose’s opposite stress on fragmentary precision.

Like Clarke’s Tibetan lamas, writers have not always resisted the message-medium conjunction; like Twain and Nietzsche, they have sometimes happily collaborated with technology’s transfiguration of their art and thereby themselves. A Twitter user recently unearthed a letter by Joyce Carol Oates in praise of Bob Dylan.

Neither the publication nor the date is given, but Oates’s piece appears to be from the late 1960s or early 1970s and uses distinctly McLuhanesque language in praise of the troubadour. Oates attributes to Dylan what she also finds in “any genius”:

“He” is both an individual and a medium, a process by which certain energies are released, and the “he”—the man, Bob Dylan—arranges and invents and occasionally exploits the forms in which these energies are released.

Oates puns on at least two meanings of “medium”: both a form of communication and one who channels spirits. As in Clarke, we find the conjunction of the technological and the supernatural, the conviction that the latter may materialize the former better than archaic means ever could. Oates also draws on the Romantics’ favorite metaphor for the poet, the Aeolian harp, a musical instrument fashionable in the 19th century meant to be placed in a window and played by the air.

The poet, the artistic genius, is “him”-self (or perhaps “it”-self) a machine receiving impressions from the beyond. This is why the immoral behavior or untoward political attitudes of geniuses are never sufficient to invalidate their achievement, and, paradoxically, also why artists should never regard their gift as special dispensation to behave vilely. You qua you are not the point: you only have make space for the wind to blow through you, “to stand in front of the public and God and obliterate yourself,” as Lydia Tár rightly tells the students at Juilliard, despite her own ironic misbelief that her talent exempts her from professional ethics or common decency.

I don’t intend to suggest with these speculations that magazines should accept spam submissions generated by AI content farms, that writers should use this technology irresponsibly as what amounts to a form of plagiarism, or even that I myself am interested in writing prose with or alongside generative AI (I’ve toyed with image-generating AI but not the writing kind). A belletristic technological naïf, I can’t adjudicate between the rival claims that AI will destroy us all or create a utopia. I also don’t want play the part of the maddeningly blasé progressive who just shrugs and tells you the date when you make an apt objection to current conditions: “It’s 2023, bro, get with the times!”—as if we were meant to bow down like servants before every product of human will (which all technology is), or as if (for example) almost all of Socrates’s complaints about what writing would inflict if it displaced speech weren’t fundamentally correct. Erik Hoel may well be correct when he says we ought, even at the risk of overstatement, to incite social panic about AI before it makes good on its existential threat to humanity (though his advice that we follow the model of museum-vandalizing climate doomers—to my mind, almost entirely unsympathetic figures—doesn’t inspire confidence).

For all the cogency of Socrates’s objection, however, writing, like all technology, has affordances of its own. For one thing, how else would we know about Socrates? The story of humanity’s literary collaboration with technology can be told dystopically as the almost unremitting triumphal march of the machine, dragging captive humans in its wake, and heading smugly toward the end of the world. From another perspective, though, the human medium has proved irrepressible, has never been wholly silenced by its apparently senior partner, the inorganic in all its forms from writing itself to the printing press, the typewriter, and generative AI.

Around the same time as Twain and Nietzsche started typing, Henry James began dictating his fiction to a secretary-typist. James had previously composed his fiction with a pen, but he turned to dictation after he found his writing hand cramped by a repetitive stress injury, just as eye disease forced Nietzsche to adopt an early typewriter itself developed for the use of blind people. This particular union of human and machine, again as in Clarke’s fable, fuses the most ancient form of composition—the bardic—with the most modern—the machinic—almost as if to suggest their kinship. (His most famous ghost story, The Turn of the Screw, was one of the first works he produced this way, reminding me that Arthur C. Clarke’s science-fictional peer, Ray Bradbury, described his typewriter as a Ouija board in a televised interview.)

The overall result of this collaboration—the almost unnavigably labyrinthine style of “late James” in such classic novels as The Wings of the Dove and The Ambassadors—proved to be one of the most distinctive of modern literary personalities, the very prose people think of when they think of “Henry James,” and the opposite of the Twain-Hemingway journalistic vernacular style, rendered opposite, presumably, by James’s use not of the typewriter alone but of the typewriter in conjunction with the voice (in conjunction, too, with the female typist, for whose own longings and travails see Cynthia Ozick’s novella Dictation). The rendezvous of archaic voice and modern machine, far from dehumanizing the penman James, allowed his flourishing as the most perfected example of himself. Instead of technology determining literature, and contra McLuhan, we might speak about the literary determination of technology.

Similar, poststructuralist French literary theory, inexorably anti-humanist, was endlessly fascinated by the idea that language and all the other structures we live within not only shape but wholly constitute us. Hence Roland Barthes’s famous “death of the author”: there is no author, only a site for disparate forms of writing to converge. This theory superficially resembles Oates’s praise of Dylan as medium or the Romantics’ vision of the poet as Aeolian harp, but it crucially misses the spiritual dimension creative writers like Oates or Coleridge invoke without embarrassment, spirituality being permissible as an object of study but not as a conviction or even speculation in secular academe.

Accordingly, in their book, Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature, French theorists Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari refer not to Kafka as author. Instead, noting Kafka’s war on conventional representation, and likely inspired by the torture device as writing implement from his “In the Penal Colony,” they describe instead the “Kafka-machine,” productive of all the specific ideas and affects, concepts and images, we might gather under the rubric “Kafkaesque”—a way of reading that evades what the French theorists regard as a merely sentimental interest in the writer’s existential suffering:

A Kafka-machine is thus constituted by contents and expressions that have been formalized to diverse degrees by unformed materials that enter into it, and leave by passing through all possible states.

As a rigorous approach to Kafka’s text, interested in its machinic combinations and permutations of discrete elements rather than in its personal impetus, this method—call it “The Nine Billions Names of Kafka”—has its advantage, since the biographical can indeed become lugubrious in literary criticism. But for all the novel literary machines Kafka set in motion, one looks up at the screen as Clarke’s engineers look up at the sky and finds not the end of the world but something almost as startling: Kafka, the Daily Mail reports, has become a romantic icon and heartthrob for adolescent (or might-as-well-be-adolescent) girls on TikTok.

In Clarke’s fable, artificial intelligence brings the end of creativity—and thus of the creation—by helping us to discover reality’s every possible configuration. The putatively machinic Kafka’s belated but warm-blooded TikTok celebrity suggests, however, that the machine in collaboration with the human will continue to surprise us with novelties unpredicted by our most careful calculations. As it has in the past, the human may prevail not over but through the machine.

John Pistelli writes Grand Hotel Abyss.

Twain, Dylan, Dickens, McLuhan, and Bradbury weaved into and out of the conversation, and thankfully our minds have been opened by all of them. Thanks for this far ranging piece that began with technology altering our world, as it's been doing for centuries, and now at an accelerated pace.

I suppose anyone writing formulaic romance novels ought to fear the new AI, and I've seen some intelligent commentary on how it might automate soul-enervating tasks like writing radio ads for local businesses. There is a human cost here, if it then requires fewer people to write radio ads, but it's typically a losing argument to try to defend human labor when the labor itself is not meaningful.

I've not yet seen anything produced by ChatGPT that ought to make literary writers worry, and clearly there can be no substitute for immersion journalism, since AI cannot walk through flooded streets or war zones interviewing suffering people.

Your point about the typewriter or the dictation-typewriter combination transforming prose style is interesting. Since AI seems to be able to imitate most prose styles, it seems a revolutionary technology in that way, and one that might seem to foreclose the possibility of innovating away from it. Even so, there is no evidence, is there, that AI could produce a fully realized bildungsroman or anything approaching James Baldwin's sentences or Toni Morrison's sensibility?

I lose the thread somewhat in your discussion of Dylan, and the subsequent comparison of humans to machines vis a vis the Aeolian Harp. The Romantic notion of channeling in that way is not at all machine-like, is it? Epiphany was/is a key part of that conceit, and it seems inconceivable that AI has the potential for sudden insight or inspiration.

I think about this similarly to Ellen Ullman in her fine 2004 essay "Dining with Robots." A robot will never be capable of enjoying a gourmet meal or the interhuman pleasure of speaking to farmers or ranchers at an open-air market in preparation for the meal. Ullman reflects, while visiting a supermarket, that instead of robots becoming more humanlike, they have made humans more robotic. That, to me, is the real danger of ChatGPT. It's not necessarily the end of innovation, but it might mark the end of readers' appetite for innovation. Those of us who need to create art or to struggle with things in essay form will assuredly continue doing so, but whether we'll have readers is another question.