Fleeting Cherry Blossoms and Transformative Art

Discovering the gift of art in Jakuchū’s scrolls, Colorful Realm of Living Beings

The centennial of the gift from Japan to Washington, D.C., of 3,000 cherry blossom trees coincided with the gift from that same country of Colorful Realm of Living Beings, the stunning bird-and-flower 2012 exhibit at the National Gallery’s West Wing.

As a journalist at the time, I was able to join the invited guests and experienced an uncrowded premiere: The paintings still resonate with me.

Both the blossoms and the paintings by Jakuchū, the artist whose work soars, were fleeting: the blossoms drop almost as quickly as soon as they appear and this exhibit that I was lucky to attend lasted only 5 weeks.

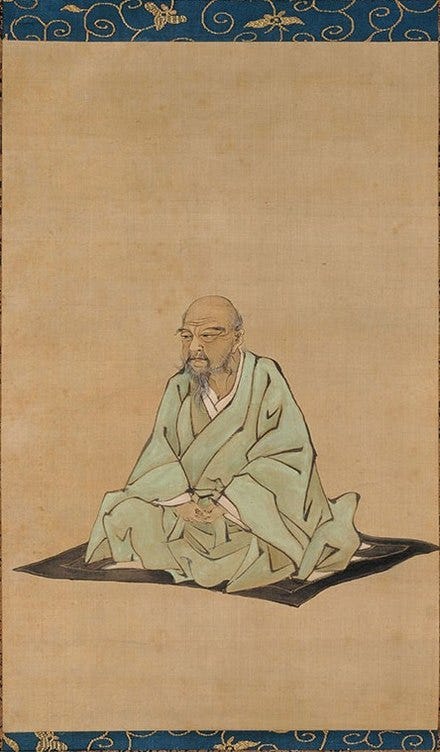

Itō Jakuchū (伊藤 若冲, 2 March 1716 – 27 October 1800) was a Japanese painter of much renown and his works are held in several museums worldwide, including the Idemitisu Museum of Arts, the University of Michigan Museum of Art, the Miho Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art,[11] the Harvard Art Museums, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Indianapolis Museum of Art, the Asian Art Museum, the Yale University Art Gallery, and the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Both the blossoms and Jakuchū’s paintings share the unselfconscious quality of beauty, given and created, and both teach us while they enlighten.

The trees given over a hundred years ago are living testimony to the power of a gift that stands in the face of what can be argued is its opposite: commerce. According to the U.S. Census, we imported in 2011, as one example the year before the exhibit ran, 128,811 million dollars worth of goods from Japan. That strong trade-based exchange has survived even our history of war that followed the gift of the cherry trees.

The paintings, more than two hundred years old, are testimony that creative work, the best of it, rarely originates in commerce but instead in the spirit of the gift that the cherry trees exemplify.

The exhibit, Colorful Realm of Living Beings (c. 1757–1766) was a 30-scroll set of bird-and-flower paintings seen in its entirety at The National Gallery for the first time outside Japan. These extraordinary, light-filled paintings provide a panoramic of flora and fauna, both mythical and actual.

In 1765 Jakuchū donated Colorful Realm (then comprising 24 scrolls) and the triptych of the Buddha to Shōkokuji, where they were displayed in a large temple room during Buddhist rituals. Colorful Realm was donated to the Imperial Household in 1889; since then, at the time of the premiere I attended, it had been shown together with the triptych only once, in 2007 at the Jōtenkaku Museum, Shōkokuji.

I was struck by the originality, the spontaneity, the sense that the birds and flowers, painted with mineral pigments, lift off the silk weave and join with you the viewer as if you are one. This quality, this forgetfulness of one’s self, is the essence of how art gets made and received. We know it when we see it and stand in its awe as I did in front of Jakuchū’s scrolls.

Jakuchū’s personal story inspires the search for the creative soul inside us all. Born in 1716 the son of the Masuya wholesaler that lent out space to Kyoto’s grocers in a neighborhood that still serves as a marketplace for food, he left the family business that had earned him both wealth and social status in 1755 to paint and continue his practice of Zen Buddhism.

Jakuchū built on the traditional Japanese pictorial meanings, such as plum blossoms and cranes for longevity; the phoenix for the imperial; the peacock to represent culture and prosperity.

What emerges in Jakuchū’s depiction of these subjects startles.

As one example among the 30 on display, Jakuchū’s peacock rises from the silk with his use of gold paint on the eye and the tail, an application that is opaque and in direct contrast to the transparency he preferred.

In this scroll, entitled “Old Pine Tree and Peacock,” we see the silk surface inside the paint among the feathers of the tail.

This transparency in each of the scrolls gives the paintings and its subjects a surprising sense of light in the windowless room where they were displayed. The light comes from the art and Jakuchū’s heart.

When I stood before these scrolls, I felt joined with Jakuchū in his journey of light.

This forgetfulness of the self is the subject Lewis Hyde addresses in his book The Gift, where he argues that the artist must submit himself to a “gifted state,” one in which he is able to discern the connections inherent in his materials … and to bring the work to life. … Sometimes, then, if we are awake, if the artist really was gifted, the work will induce a moment of grace, a communion, a period during which we too know the hidden coherence of our being and feel the fullness of our lives.

The cherry blossoms bloom year after year out of their gnarled bark and remind us of nature’s gifts. Jakuchū’s paintings remind us of those same gifts and the lasting power of art.

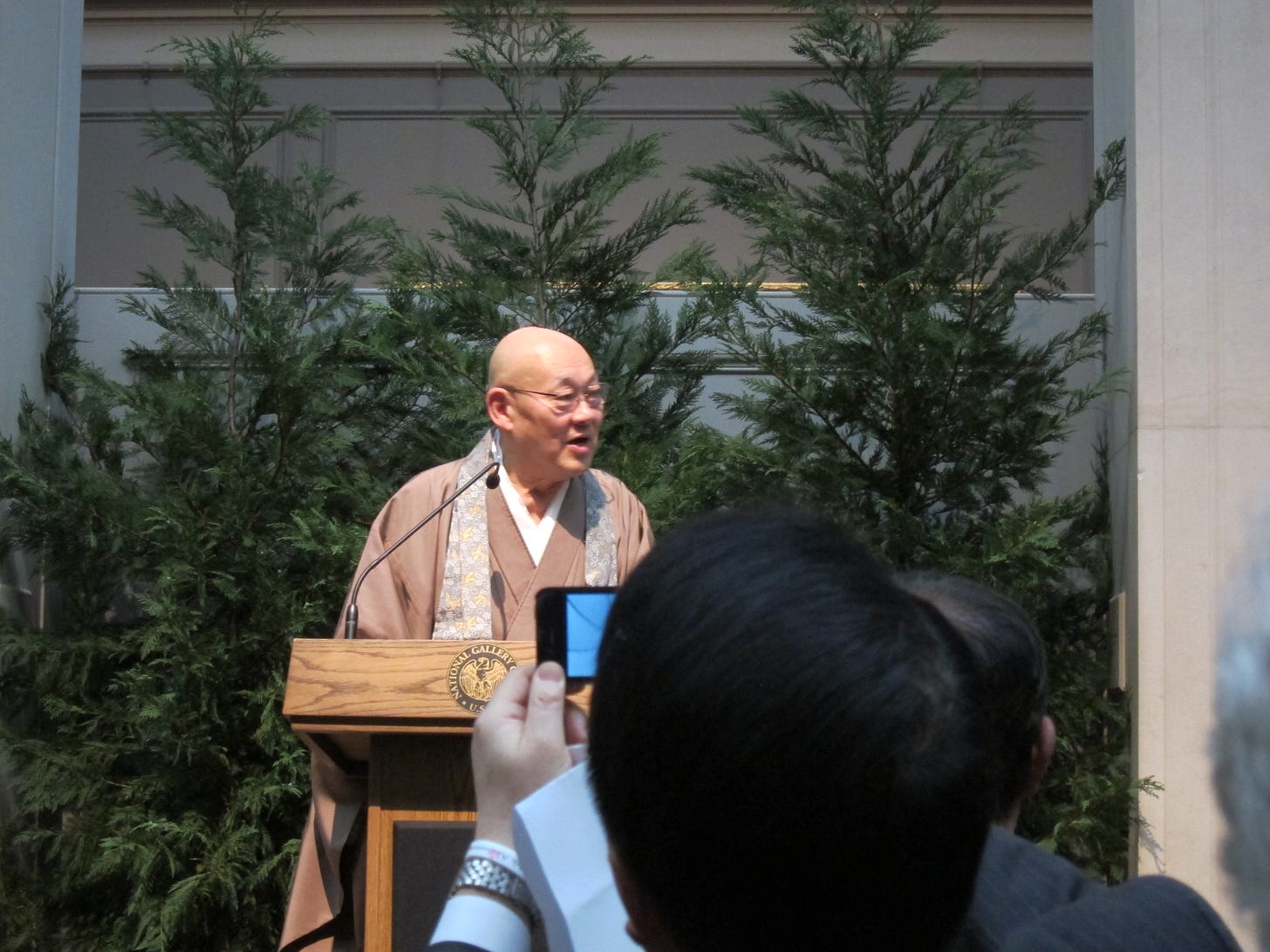

But do not forget nature’s power to destroy. March 2012, when the exhibit opened, also marked, as many of the speakers at the exhibit’s opening noted, the anniversary of the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and the tsunami that followed. That natural disaster reminds us of nature’s destructive power and that the fleeting gift of beauty should not be missed.

I joined my heart with Jakuchū’s heart 200 years later and connected in a communion that I cannot do justice to here—but what is missing here I found in front of the scrolls.

If you watch closely, you’ll see me in this video that follows as one of the in-awe viewers (Let me know if you caught that glimpse :) Here’s the marvelous video:

Following: a few of the many photos I took with my itty bitty camera:

.

Our next guest essayist, looking forward, will be Russell C. Smith who writes

Mary Tabor writes

The best classic Japanese art never fails to astound!

This is beautiful, Mary. Thanks for your gorgeous prose and photos. I needed this today!