Mary McCarthy’s Curious Confession

The Close Read: Missing in Memoir 3

Third in a series in which I consider absences in literary memoir: gaps of information or in logic, or aporia – contradictory elements in a text that produce similar absences, of sense or understanding; how close textual and contextual reading of absences produces deeper understanding.

Mary McCarthy’s 1952 confession in “My Confession” is ironic. Sort of. Or maybe it was a different kind of confession, about something other than what she professed to have confessed. I don’t know, I confess. But it is peculiar, if little noted as such.

When she died in 1989, McCarthy – essayist, novelist, critic, memoirist, scathing wit, and literary executor for Hannah Arendt – was best known to many for the $2.5 million defamation lawsuit playwright and memoirist Lillian Helman pursued for five years against her , until Hellman’s death in 1984. The suit followed from a McCarthy appearance on the Dick Cavet late-night talk show (unusually popular amongst the literary and intellectually inclined at that time), in which McCarthy declared of Hellman, "every word she writes is a lie, including 'and' and 'the'."

Fodder for this damning judgment had been forked over by Hellman herself, in a series of autobiographical books over those recent years that were abundantly and variously revealed to maintain a dubious hold on the truth. But the enmity between the two women extended back decades in time. Between the 1930s peak of Communist influence in the United States to the anti-Communist witch-hunts of the late 1940s and early 50s, the two writers of the left charted distinctly divergent paths. McCarthy, who never actually joined the Communist party, turned sharply against it in response to Stalin’s show trials, purges, and banishment of Leon Trotsky. Hellman did not. Hellman continued to defend Stalin. She refused to name names to the House Un-American Activities Committee, and in a May 1952 New York Times essay declared, “To hurt innocent people whom I knew many years ago in order to save myself is, to me, inhuman and indecent and dishonorable. I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year's fashions."

That so high a horse was saddled in support of Joseph Stalin, who showed little regard for the principles of the First and Fifth Amendments during the Great Terror or after, enraged many, including McCarthy. But others were naming names, and confessing, and it was in response to those confessions that McCarthy – who, as a non-Communist, anti-Stalinist socialist, had nothing of the kind to confess – published “My Confession,” in the May 1954 Encounter.

By this point McCarthy had published the famous short story “The Man in the Brooks Brothers Shirt,” produced several scandalous novels drawn closely from her own recent life, penned over a decade’s biting cultural criticism for The New Republic and The Nation – with a like period on the editorial staff of Partisan Review – and ended her tumultuous eight-year marriage to Edmund Wilson. She was well on her way to becoming, according to Norman Mailer, in the New York Review of Books, the “First Lady of American Letters . . . our saint, our umpire, our lit arbiter, our broadsword, our Barrymore (Ethel), our Dame (dowager), our mistress (Head), our Joan of Arc.” Mailer, never haunted by the hobgoblin of consistency, also wrote of her in that review of her most famous novel, The Group, that she was a “duncey broad” who was “simply not a good enough woman to write a major novel.”

“She was a great wit, but she was not a great thinker,” said Isaiah Berlin. “Mary was essentially a polemical writer,” claimed Irving Howe. “[She] didn’t write . . . for the ages. It was always in response to something.”

The misogynistic notes aside, Rob Madole tells us that Howe’s last comment is an essential critique of McCarthy, “that McCarthy didn’t stand for anything. That her writing, in its relentless sending up of hypocrisy and self-regard, didn’t put forward its own point of view” – or as Mailer put it, “a view of the world which has root.”

Madole disagrees, but this question comes to the fore in “My Confession,” which begins:

Every age has a keyhole to which its eye is pasted. Spicy court-memoirs, the lives of gallant ladies, recollections of an ex-nun, a monk’s confession, an atheist’s repentance, true-to-life accounts of prostitution and bastardy gave our ancestors a penny peep into the forbidden room. In our own day, this type of sensational fact-fiction is being produced largely by ex-Communists. Public curiosity shows an almost prurient avidity for the details of political defloration.

We actually do see here, as far as it goes, a “view of the world which has root.” McCarthy believed that good novels were all about the social milieu and gossip. (Hers certainly were.) She pointed out that the second sentence of Anna Karenina is “Everything was in confusion in the Oblonsky’s house.” “My Confession,” like McCarthy’s novels, offers plenty of gossip, with the writer’s usual keen eye for social mores and behaviors – a social scene. Making the cocktail and dinner party rounds in politically engaged, literary 1930’s New York, we see and learn what McCarthy learns: that young intellectually au current writers, artists, and academics may be better educated, more in-the-know, more charismatic, and wittier than many of their neighbors, but they are just as vain and ambitious, foolish and unfaithful, sexually greedy and fearful, and generally clueless as anyone else before the slow, swarming offensive of history against their lives.

McCarthy sets that scene of her essay’s then beside its now, the period of early 1950s public confessions, and the stories those confessions unfold:

Two shuddering climaxes, two rendezvous with destiny, form the poles between which these narratives vibrate: the first describes the occasion when the subject was seduced by Communism; the second shows him wresting himself from the demon embrace.

She sums:

These people, unlike ordinary beings, are shown the true course during a lightning storm of revelation, on the road to Damascus. And their decisions are lonely decisions, silhouetted against a background of public incomprehension and hostility.

I protest.

It is all too dramatic for McCarthy, too much a crucible of character forging a hitherto uncreated conscience. What does she set forth, in Mailer’s terms, as her root-view of the world?

In fact, I have never known these mental convulsions, which appear quite strange to me when I read about them, even when I do not question the author’s sincerity.

Is it really so difficult to tell a good action from a bad one? I think one usually knows right away or a moment afterwards, in a horrid flash of regret. And when one genuinely hesitates--or at least it is so in my case--it is never about anything of importance, but about perplexing trivial things, such as whether to have fish or meat for dinner.

This is all in the first four paragraphs only, and one might be well supported if a skeptical, silent hmm forms in the mind at this point that continues to buzz all the while one reads. McCarthy completes the setting of the stage for her confession:

For me, in fact, the mark of the historic is the nonchalance with which it picks up an individual and deposits him in a trend . . .. Like Stendhal’s hero, who took part in something confused and disarrayed and insignificant that he later learned was the Battle of Waterloo, I joined the anti-Communist movement without meaning to and only found out afterwards, through others, the meaning or "name" assigned to what I had done. This occurred in the late fall of I936.

The key acts, or non-acts, are yet to come, but some further pre- and post- textual facts enrich the context. So soon after our own pandemic, we should know that both of McCarthy’s parents died in the 1918 flu epidemic. She, age 6, and her three siblings, including the actor Kevin McCarthy, were taken in by an oppressively harsh, physically abusive great uncle and aunt, with whom the four lived until they were rescued after five years and dispersed, Mary to their grandparents. In 1957, McCarthy would publish Memories of a Catholic Girlhood, in which she offers her account of that childhood, and of her loss of faith, all set against contradictions and revisions of her memories that she provides based on further research and consultation with family and friends. In the light of those contrasting accounts, McCarthy allows evidence that she had misremembered many details.

After the events of “My Confession,” after WWII – with the American left’s and literary world’s 1930’s engagement with Marxism fractiously dividing its ranks, as it does still today – McCarthy played significant if not leading roles in the Europe-America Groups, the American Committee for Cultural Freedom (American CCF), and publishing in Encounter. Large numbers of the leading, left intellectual and literary anti-Communists of the early Cold War era belonged to CCF and many published in Encounter, both of which, unbeknownst to most of them, but known to some, received funding from the CIA. There, McCarthy published her 1954 faux confession regarding her defense of Leon Trotsky.

In the essay, McCarthy is at pains to describe herself as not, seriously, a political person. She held left political views, but she was a woman of letters, unschooled in the ideology, and making the rounds at the parties in order to make the scene, make a career, make love, and make skewering commentary on all she surveyed. In typical McCarthy fashion, she manages superbly to revere and revile the true believers in the same sentences:

The superiority I felt to the Communists I knew had, for me at any rate, good grounding; it was based on their lack of humour, their fanaticism, and the slow drip of cant that thickened their utterance like a nasal catarrh. And yet I was tremendously impressed by them. They made me feel petty and shallow; they had, shall I say, a daily ugliness in their life that made my pretty life tawdry.

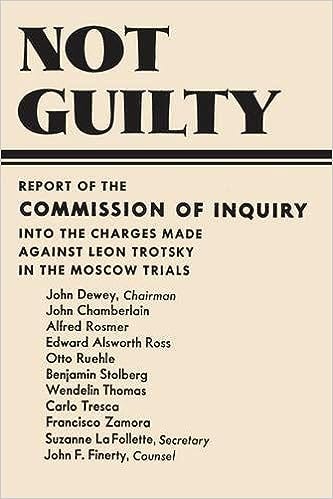

At one of these parties, McCarthy tells us, Stalin’s purges already in progress and Trotsky exiled, she feels uncomfortably, ignorantly cornered within a crowd of listeners: does she agree or not that Trotsky deserves a hearing on the charges against him, that he warrants asylum? Why, yes, sure, of course he does, who wouldn’t, yes. Are these serious questions? In fact, with Sydney Hook one of the organizers, an independent and purely symbolic commission to judge the charges is already in the works, to be chaired by none other than Hook’s mentor, John Dewey: the Dewey Commission, as it became popularly known.

This represents the advent of McCarthy’s Trotsky advocacy:

Four days later I tore open an envelope addressed to me by something that called itself "Committee for the Defense of Leon Trotsky," and idly scanned the contents. "We demand for Leon Trotsky the right of a fair hearing and the right of asylum." Who were these demanders, I wondered, and, glancing down the letterhead, I discovered my own name. I sat down on my unmade studio couch, shaking. How dared they help themselves to my signature?

McCarthy would have none of it.

My own feelings were crisp. In two minutes I had decided to withdraw my name and write a note of protest. Trotsky had a fight to a hearing, but I had a right to my signature.

But she did not withdraw her name. Why did she not?

In “Taking Sides: Mary McCarthy’s unsparing honesty,” Maggie Dougherty explains it this way: “She was furious that the committee had used her name, but once acquaintances started to discourage her from taking up Trotsky’s cause, she resolved to stay and threw herself into the cause.” McCarthy wasn’t alone. Many people received these warning/threatening calls. Many did remove their names. Somewhat differently, in “The Bitch Is Back: A Reappraisal of Mary McCarthy for the 21st Century,” Sabrina Fuchs Abrams describes the pivotal incident thus: “This seemingly accidental conversion to Trotskyism was a defining moment in her personal and professional life.” It was indeed defining, but where was the accident? McCarthy’s name was not assigned to the letter by accident, nor did she fail to remove it by accident, though she seems intent on creating that impression. Neither Dougherty nor Abrams includes the first part of McCarthy’s explanation for what transpired.

The "decision" was made, but according to my habit I procrastinated. The severe letter I proposed to write got put off till the next day and then the next. Probably I was not eager to offend somebody who had been a good friend to me. Nevertheless, the letter would undoubtedly have been written, had I been left to myself.

“Undoubtedly” – after days of procrastination. The “probably” here, too, has the ring of Joyce Carol Oates, in “They All Just Went Away,” averring that she could not recall whether she had left her change purse on a window ledge in a high school bathroom by accident or to test her friend’s honesty – even though she waited for the friend to exit the bathroom before entering to retrieve it. Now, as then, I think, we have reason to call on our resident literary psychotherapist, Dr. Spielvogel, to pause and redirect his conversation with the person on the opposing couch, by saying, “But I want to go back to when you said you ‘procrastinated.’” The patient stares blankly. “Do you think there might be reasons why you ‘procrastinated’ – or more to consider than ‘probably’ not wanting to offend a friend?”

Well, we’ll leave the therapist and his client to their privacy, but McCarthy offers further:

Of course, I did not foresee the far-reaching consequences of my act--how it would change my life. I had no notion that I was now an anti-Communist, where before I had been either indifferent or pro-Communist. I did, however, soon recognise that I was in a rather awkward predicament--not a moral quandary but a social one. I knew nothing about the cause I had espoused; I had never read a word of Lenin or Trotsky, nothing of Marx but the Communist Manifesto, nothing of Soviet history.

One has to observe first that McCarthy’s “act” here did not in any way make her an “anti-Communist.” Most of the people haranguing her at parties to support Trotsky were themselves Communists. Trotsky was a Communist. Her identification via that appropriated signature made her an anti-Stalinist, a damn fine thing to be and which she wore proudly (Lillian Hellman well knew) all the rest of her life. McCarthy made herself an anti-Communist over the years following, by any number of her own overt commitments and expressed ideas, including breaking with her old Partisan Review friends and Trotsky-defending socialists when they evolved too much into Cold Warriors. Choices she made. Second, we see here again McCarthy at some pains to diminish her own seriousness of purpose and the very consequentiality of her own engagements.

Indeed, if we think back to McCarthy’s introduction of her essay’s topic, we can be led to question what truly her purpose was in writing the essay? What exactly is she confessing? That she, like those she mocks to start – repentant before congressional committees – had been, with considerably less self-importance and anxiety, a Communist? She hadn’t been, and everyone knew it. That she once defended Trotsky? She offers no apology for that, and Trotsky was long dead and on no one’s mind but in small coteries of Fourth International-inheriting, internecine-warring, socialist-worker-party aspirants to the age of permanent revolution. If one reads closely, and it doesn’t need to be all that close (when she then closes as she began by choosing to recede from significance) McCarthy’s true aim is a kind of delayed revenge on all those grave and moralizing Commies from the 30s. No crucibles of conscience for Mary McCarthy (Arthur Miller); she procrastinates and worries fish or meat for dinner.

Over the past thirty-five years of McCarthy scholarship and criticism, since her death, often in periods of “reconsideration,” there has often been fervent attestation, as in Dougherty’s title above, to McCarthy’s fierce “honesty” and commitment to facts and “the truth.” One reads this repeatedly, even though in her own writing she sometimes raises doubts about her capacity for it. (Against the terrorizing great uncle, she adopted “a policy of lying and concealment.”) Biographer Jean Strouse, in a penetrating 1992 New York Times review of McCarthy’s Intellectual Memoirs (“Making the Facts Obey”), cuts to the quick of the matter in observing McCarthy’s frequent “faux naif note” and her "endless re-enactment of that conflict between excited scruples and inertia of will."

We can see the “faux naif” in conversation with William Buckley regarding McCarthy’s anti-Vietnam War reporting. After its publication in book form, McCarthy avers perplexity at its not having been more widely reviewed. Buckley unsurprisingly attributes the case to the book’s badness. But McCarthy, acknowledging the criticism of even respected war reporter Ward Just, pretends oblivion to the possibility it was because of her having veered (in a first ironic shade of Stalin apologia) from incisive critique of the war into championing the North Vietnamese Communists.

McCarthy had in fact developed a feeling of dear friendship with Phạm Văn Đồng, prime minister of North Vietnam under Ho Chi Minh, when she visited Đồng in the North in 1968. McCarthy called Đồng “the most impressive politician I ever met” and continued a years-long communication with him.

It is fascinating, then, in regards “inertia of will,” to discover (in the spirit of Leonardo, Vitruvians are lovers of invention and discovery) that in the famous Dick Cavet interview, McCarthy commented not only on Lillian Hellman’s honesty, but was also questioned by Cavet about her relationship with Phạm Văn Đồng. By this point, the fall of 1979, Đồng was Prime Minister of the united Vietnam. By then also, Henry Kamm had been reporting on the Vietnamese “boat people” flight as early as January of that year, and Bernard Gwertzman had first reported on the “reeducation camps” in 1976.

Interviewed that same month about all this by Miriam Gross in The Observer, before the Cavet show, McCarthy commented,

I’ve several times contemplated writing a real letter to Pham Van Dong . . . asking him can’t you stop this, how is it possible for men like you to permit what’s going on? . . . I’ve never written that letter, though; it is still in my pending folder, so to speak. Of course it shouldn’t have stayed there, but it did.

Given the chance, Cavet asked McCarthy whether she had written the letter. She said she was planning to.

“I might. I don’t know.”

Cavett asked McCarthy: “Why couldn’t you call him on the telephone?”

“I hate to talk on the phone. A letter is what I ought to write. I still may write the letter.”

“Maybe you were wrong about him in the first place?” Cavett said.

McCarthy expressed her doubts: “I don’t think one can be. I’ve got photos and so on—and you look at his face and . . ..” She offered further defenses based on Đồng’s age and real hold on power.

The echoes of McCarthy’s dissimulating denial and avoidance in accounting for her behavior in the Trotsky signature incident are startling, the reversal of her behavior in response to Stalin perplexing.

Finally, to close “My Confession,” in casting her diffident decision-making more attractively against the self-importance of others, McCarthy offers that “I have a surprise witness to call for my side.”

Leon Trotsky.

McCarthy cites Trotsky, from his autobiographical My Life, presenting “[o]ne factor in his losing out in the power struggle” after Lenin’s death: “his delay in getting the telegram” about Lenin’s funeral – because he had gone duck hunting with a friend, stepped in a bog, and come down with pneumonia.

Leadership of the worldwide Communist revolution, signatures on life-altering letters – all determined, McCarthy would have it, by a few chance steps into swampy water and a like number of days of unaccountable procrastination.

Except if one reads the 2009 Robert Service biography of Trotsky, the most recent, one finds, first, that the duck hunt, the pneumonia, and, most significant, any reference to such events having been a “factor in [Trotsky’s] losing out in the power struggle” do not appear in it.

What one reads instead is how for more than a year, month by month, before and after Lenin’s January 1924 death, Trotsky failed to counter Stalin’s shrewd maneuverings. Even after the ailing Lenin, in January 1923, had recorded in a codicil to his final directives his repulsed turn away from Stalin in favor of Trotsky, even after Stalin, in his many stratagems, endorsed Trotsky for multiple top-level positions in light of Lenin’s absence, Trotsky rejected them all and simply refused adequately to politic within the politburo to his advantage.

But McCarthy would have Trotsky’s fate, like her own, a mere matter of chance, without the weight of individual responsibility, the workings of conscience, or considerations of consequence.

Why?

As of the time of this publication, Dr. Spielvogel has yet to make his patient notes available to the public.

“My Confession” offers rich illustration of how a text out of context – perhaps never more than in the memoirs of creative writers – received as words on paper only and not words in the world, may remain a text incompletely read, and how what is there and isn’t there are matters equally for our care.

AJA

This is so informative. And I've recently finished The Unbearable Lightness of Being which, in the scenes of Tomas' quandary to sign or not sign, lends itself to more understanding now as I read this.

This is totally engrossing, Jay. I knew nothing about this and have read no McCarthy (one of many holes in my reading of American literature), but what an interesting figure and what a strange political/literary moment. (By the way, Buckley is such a smug SOB in that interview; the man could smirk with the best of them--or the worst.)