Before I begin, I introduce my guest coming next: Adam Nathan, who has written for us once before, and who writes

Michael Kirby paints on the street

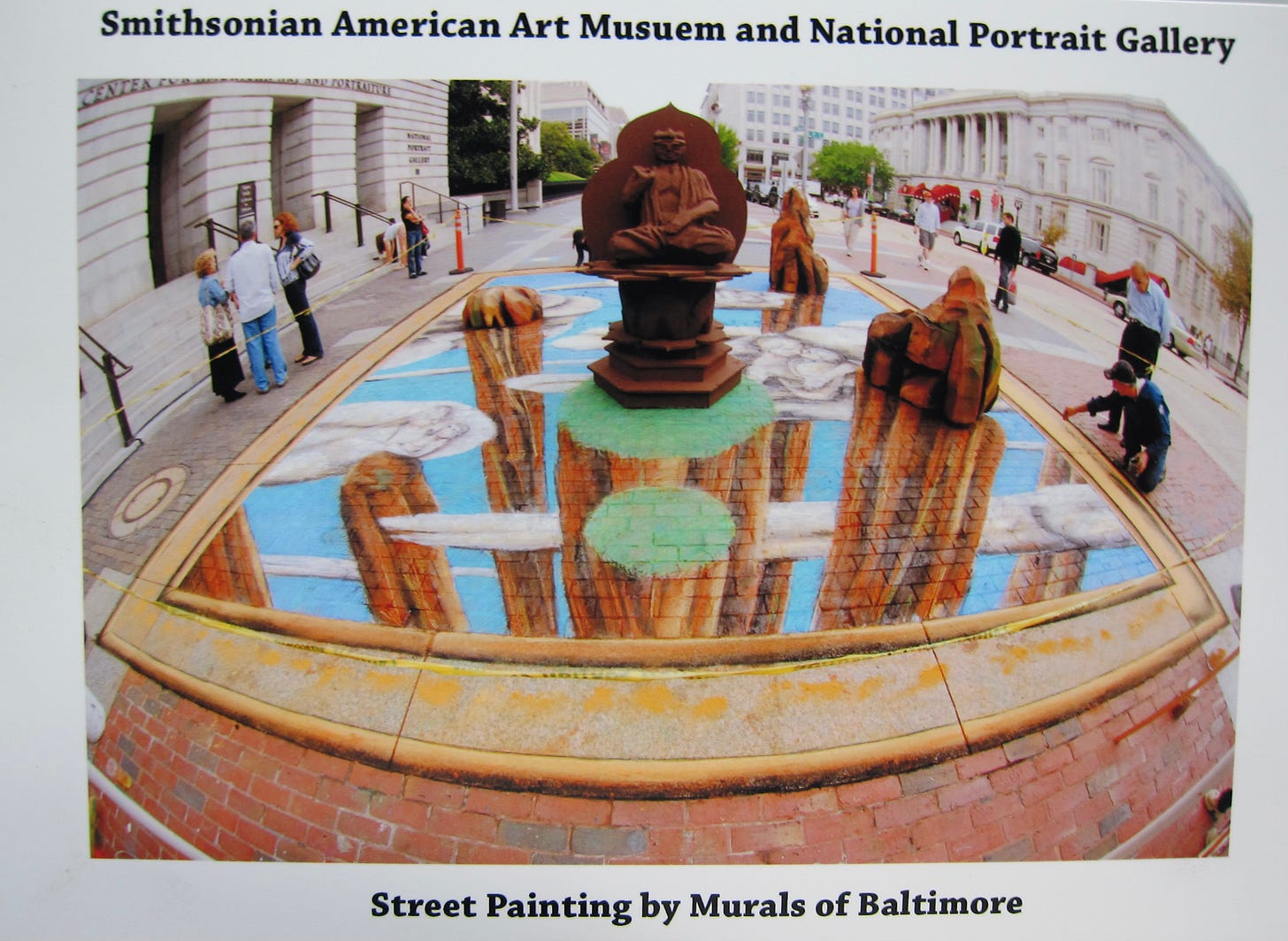

The Smithsonian commissioned Michael’s sidewalk painting.

Perhaps Bob Dylan’s most famous song defines the creative effort, its demand to love and work inside the limits of time and the erosion that comes with its passing.

Michael William Kirby, street painter, understands “here today” — painting in pastels that will wash away with rain and foot traffic — and “gone tomorrow.”

Michael, who hails from Baltimore, began a large sidewalk painting in front of the Portrait Gallery in DC as part of the museum’s Chalk 4 Peace Family Festival.

Sidewalk paintings, created in chalk, can reproduce famous works of art or create forced perspective images that make it seem as though one is standing on the top of a pole or about to step onto a mandala (see me further down on top of the pole on the finished painting).

This is just one of many cities that has featured this artist’s work.

Kirby began painting as a boy, learning the how-to’s in Italy. He’s been painting streets all over the world for over 20 years.

“I had a passion for it,” Mr. Kirby says. “I could draw but (felt) a chimpanzee could do what I did.”

As a teenager, he went to Italy where he learned that being an artist was an occupation and that he could actually make money from his drawings.

“That’s where I saw people painting Madonnas on the street in Florence and thought ‘I can do that’.” Italy is also where he met Flávio Coppola.

The artist Flávio taught him “how to control, how to look at things, how to understand movement.” And before he knew it he was “making 30 bucks a day, enough to get by and I was happy.”

Michael hasn’t been to art school but says, “I’ve had a lot of help along the way. Some people pay to learn. I was lucky enough to get taught for free.”

Michael hasn’t been to art school but says, “I’ve had a lot of help along the way. Some people pay to learn. I was lucky enough to get taught for free.”

The thing that becomes clear in this artist’s narrative is that it’s not about the money. I’m not saying he doesn’t need it or want it. I’m saying that the passion came first and the “30 bucks a day, enough to get by,” speaks volumes about Michael’s seeming awareness.

He views the pieces he creates as “public art, in that realm,” emphatically adding, “and not what I consider fine art.”

This, while I sat there on The Portrait Gallery Steps looking at “Love”— depicted in the captured moment of a kiss that emerged on the pavement.

He said that fine art gallery collections are really about inner reflection, as if what I was seeing in Michael’s work was not.

I respectfully disagreed because as I was looking at Michael, yes, his face, I could truly see him in his work – down on the pavement.

He deferred, “Sure this is always about me, but in my consciousness I understand that this has got to be interpreted by the outside world. It’s very easy to go into a gallery expecting the unexpected, but what I do is in-your-face, guerilla type marketing.”

He worked from a Tuesday through the following Saturday, but couldn’t work at all on Thursday because of rain.

On Saturday when he thought he’d be finished, he did the borders and made a decision about whether to use the Buddha statue he’d created in his studio.

Ultimately, he took Buddha down and put up a peace sign.

“This one’s about love, family, unity, embracing, tranquility, safety.”

And inside his painting, I saw those abstractions made concrete in the embrace of lovers, the hold of a mother’s arms around her child and calm seas that hold these images.

While Michael finished, The Smithsonian set up tables with tubs of chalk and invited anyone walking by to “paint” on the sidewalk. Children and adults did.

Some of us got our photos taken inside Michael’s painting, inside his self-reflection, and, if we looked, saw a reflection of ourselves.

Do we know where we’re going when we go after our passion?

“I don’t know where I’m going when I begin,” Michael says. “I have a general idea of where I would like to take it, but everything changes as time goes by.”

If you were lucky enough to see this exhibit, you came upon the unexpected without expecting it.

When the Smithsonian’s white canopy was gone,

when in the early dusk folks walked across Michael’s street painting as if it weren’t there, while I knew the rain would wash away his work, I learned again that to do the work of your heart is not about the money.

It’s about the love.

Michael’s studio Murals of Baltimore is in Fells point where he lives. He grew up in northeast Baltimore, the Herring Run Park neighborhood. He journeys all over the world to paint his heart on the ever-changing canvas of the street.

Mary Tabor writes

Gorgeous, Mary. This reminds me on a smaller scale of the wire walker Philippe Petit, who considers himself an artist, not a stuntman.

What a lovely, unexpected example of what drives every artist. Thank you!