My Summer with Middlemarch

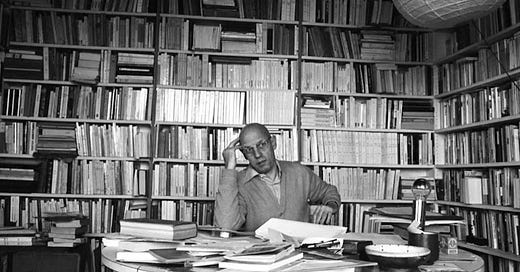

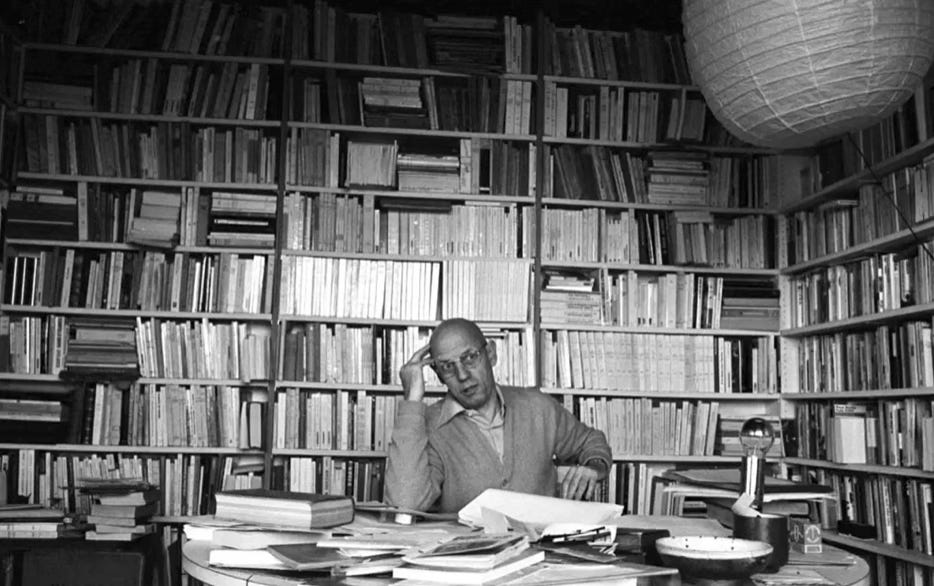

Closely reading George Eliot's 1871 classic and being inspired (again!) by Michel Foucault

When I am feeling thrown about inside myself, those times when I’m unable to access the part of me who confidently makes decisions and am feeling trapped in the part of me who spends hours doomscrolling, I eventually make my way back to “The Masked Philosopher.”

It took me years to track down a full print copy of this 1980 interview with Michel Foucault. I had come across an excerpt in a piece of literary criticism, in which the author quoted Foucault as saying: “Criticism that hands down sentences sends me to sleep; I’d like a criticism of scintillating leaps of the imagination.” I always wanted to know what else Foucault wanted from criticism.

I craved the larger context of his wish because he was, and still is, my favorite “critic,” though I believe he’d balk at the tidy categorization of that term and seek to problematize and deconstruct it.

Such was his way, and such continues to be my greatest learning from him.

You see, I’m a “literary critic” by academic credentials. I have my PhD in literary studies. I’ve presented work at over 25 national conferences, been published in a few academic journals and have peer reviewed work for a few others. And though I work in the corporate world for my 9-5 now, I also run Closely Reading, a literary and academic-ish Substack newsletter.

In it, I seek to bridge my academic background with my deep love for good stories in essays that wonder about books and how they impact our lives. Our Closely Reading Book Club explores the classics on slowed timelines; we spent ten weeks reading Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth last spring; another ten weeks on The Age of Innocence. We’ve done a few others, too. Most recently, ten weeks with Austen’s beloved Pride & Prejudice.

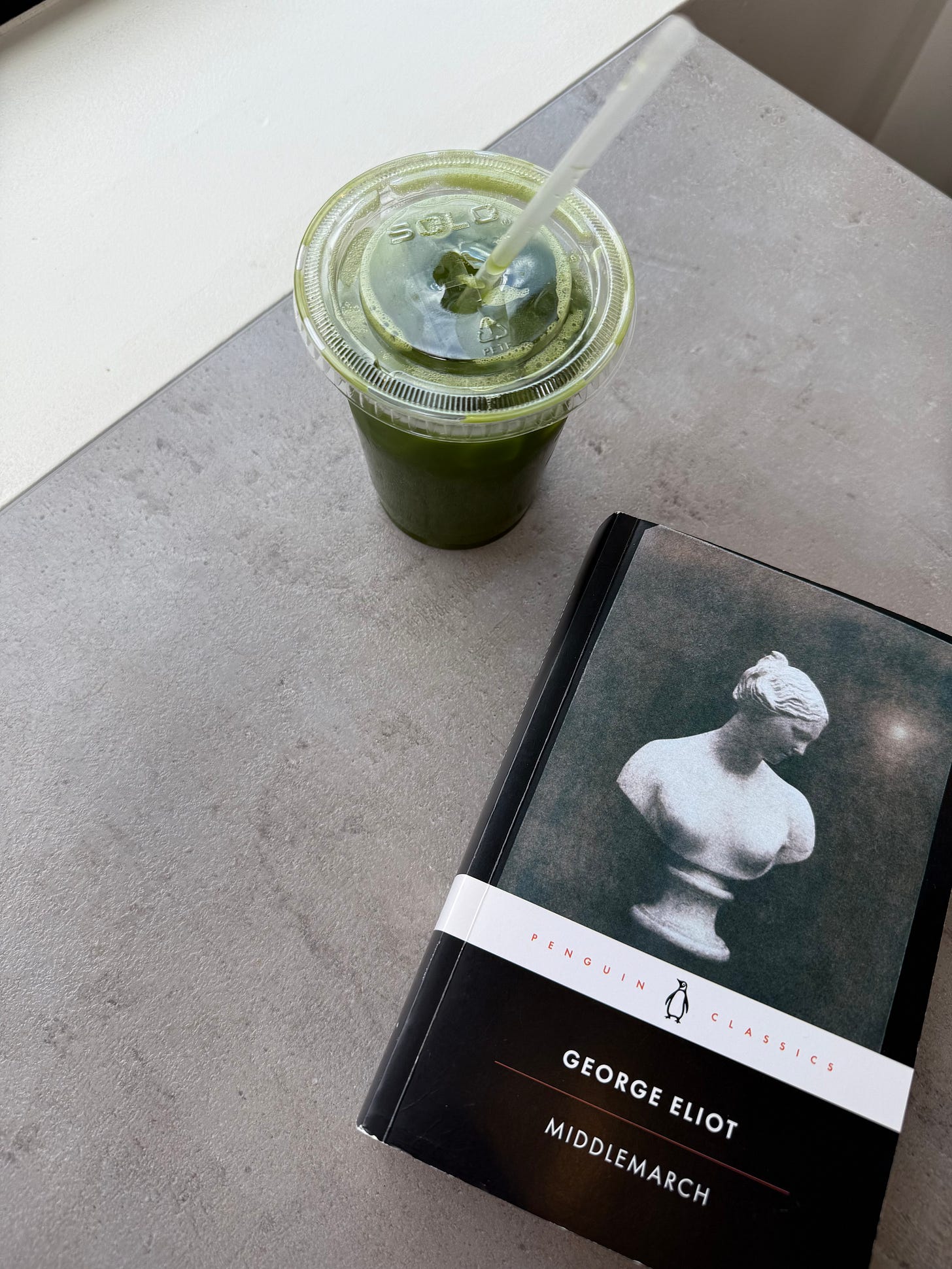

This summer, we’re reading Middlemarch.

I have found myself surprisingly sleepy while reading George Eliot’s 1871 tome. Sometimes, her “sentences sen[d] me to sleep,” and I dream of more “scintillating leaps” from the prose. I think about Eliot’s goals when I hit a particularly droning section of story, as when the narrator—almost blue in the face—defends a character we’ve so far had no real reason to dislike as much as her defenses suggest.

I read her narrator waxing on and on about medical innovation or a vicar’s fishing habits, and I feel my eyes drifting. Then, I pull myself back in with questions.

Conversation is, after all, a rich source of scintillation.

Why does the narrator barrel on this way? What is her purpose?

I start to envisage Eliot herself as a keen literary critic and brilliant author, who, perhaps like Foucault, wanted more from stories. Her narrator seems to play two anxious roles: the literary critic who is eager for the reader to understand her in the best and most clear way. And the artful author, earnestly weaving an intricate social web of diverse motivations, desires, privileges, and opportunities.

When I picture Eliot’s narrator this way, bifurcated by anxiety as I often have been myself, I can’t help but re-enter the text with a bigger heart and a more curious batch of questions. I am reminded of another author who undertook fictional projects as a way to play out these roles: Hilda Doolittle, or H.D., the founder of Imagist poetry and (I believe) criminally underread fiction and analytical writer.

In her 1935 novella Nights, H.D. plays a layered role as author. She invents three perspectives through which the story of the fictional Natalia will be divulged, interpreted, and analyzed. Across all three, H.D. plays with very notion of authorial intent, the veracity of psychological interpretation (or more plainly, the efficacy of psychoanalysis, which her dear friend Freud had been working on with her for years), and literary craft.

Nights is a decidedly modern, and modernist, work of art. It is fragmented and disjointed, sensual and evocative. It is imagistic, and it is one of the most unique stories — and most uniquely crafted stories —I have ever read.

And so, when I am stuck in Eliot, feeling as though I’m attempting to tread water but am steeped in mud, I think about “The Masked Philosopher” and I think about Hilda Doolittle. I start to create an unexpected conversation between Eliot, H.D., and Foucault.

And I start to understand that there must be something to this novel that I am not yet able to see or feel. And that makes me curious.

It makes me want to ask questions. It makes me want more conversation.

In my book club, it’s part of my goal and my overall project to shift people from reducing feelings of “stuckness” to some kind of lack in themselves. We do this readily, don’t we? “I’m not smart enough to read that book,” or “I just don’t understand those Victorians,” or “I don’t think I have the patience for all that.”

This, I believe, is a taught reaction that we’ve naturalized. It is not an instinct, but learned. We’ve been trained to fool ourselves into believing lazy judgments of ourselves (and by and about others) so much so that we become defensive in the face of unknowns. We turn to easy judgment.

Foucault has much to say about this in the full interview:

“It’s amazing how people like judging. Judgement is being passed everywhere, all the time. Perhaps it’s one of the simplest things mankind has been given to do. And you know very well that the last man, when radiation has finally reduced his last enemy to ashes, will sit down behind some rickety table and begin the trial of the individual responsible.”

We like judging because, as Foucault says, it’s simple. It’s easy. And it’s really just not that interesting.

As we closely read big, tough books together, I remind my readers of this as often as I can. Your judgment of a book is only part of your reaction to it; what is underneath your quick assessment of this event or that character? What is the conversation you are having with this book, without realizing you’re only one half of it?

Foucault’s thoughts on judgment tee up his dream for a better kind of criticism. He’s speaking more broadly — not just about literary criticism but the act of being a critic, or being someone who thinks publicly about culture. He says:

“I can’t help but dream of about a kind of criticism that would not try to judge, but to bring an oeuvre, a book, a sentence, an idea to life; it would light fires, watch the grass grow, listen to the wind, and catch the sea-foam in the breeze and scatter it. It would multiply, not judgments, but signs of existence; it would summon them, drag them from their sleep. Perhaps it would invent them sometimes–all the better. All the better. Criticism that hands down sentences sends me to sleep; I’d like a criticism of scintillating leaps of the imagination. It would not be sovereign or dressed in red. It would bear the lightning of impossible storms.”

When I read this in full, for the first time, Foucault’s words were “lightning” for me. What he was dreaming of in 1980 was what I had been longing for throughout my academic education and, I realized much later, what I’d been longing for since I was a little girl.

I have no interest in judgment, these days. Judgment is easy and often finite. It’s what Amanda Montell, in her book Cultish would call a “thought terminator.” After all, that’s what judgment is for: to make it unnecessary for there to be any further questions or ponderings on a given matter. Judging settles things. It puts ideas to rest.

But what of wakefulness? Of being eyes wide open inside a story? What of paying attention?

Foucault gave me language for what I’ve longed for: ways of thinking that multiply and problematize rather than provide tidy answers. Thinking that makes and unmakes us, as readers and partakers in the conversation. It has no kingly presence; it is not sleepy or cruel or thought terminating.

In these ways, this kind of thinking becomes rather threatening — to those would-be Kings, yes, and also to anyone who has a vested interest in the stability of tidy answers being the only answers.

This kind of thinking is rather rebellious.

It’s like a Mary Oliver poem, with the radical choice to spend a day watching the grass grow rather than driving productivity or optimizing your energy toward capital. It is like Whitman’s expansive, many-lined odes to the beloved world: it listens to the wind and believes what it hears. Like H.D.’s Nights, it scatters possibilities and wakes up parts of you that have slumbered for too long — and asks you where you’d go if you really were free.

This is a kind of thinking that asks and asks and asks.

That’s what I’m after when I read a book and when I seek to talk about that book with others. I want that kind of conversation: the lightning of impossible storms that spark us alive and remind us that the world is so much stranger and curious and unknown than we want to believe.

In The Age of Innocence, Edith Wharton writes, “the air of ideas is the only air worth breathing,” and each time I read it, the story happens to me all over again — a surge of impossible lightning, dragging me out of and away from those siren songs of dazed inattention that make me sadder and more anxious and lost in myself.

The challenge of reading Middlemarch this summer is being present with it.

Especially in this somewhat public way, where I share my experience of reading this novel for the first time — on the backdrop of my education and professionalization in literary criticism, but without any formal training in Eliot studies — I’ve found myself moving through all kinds of feelings. In some moments, I’ve been tempted to judge: myself, Eliot, anyone who has ever told me they love this book.

Then I remember Foucault. I remember the project of dreaming for a better kind of criticism, and I refresh my energy for the project at hand. I wonder about the anxieties of our over-reaching narrator; I wonder about my own anxiety and how it often behaves in precisely the same way: managing and defining and seeking to control. Defending men who, perhaps, haven’t always deserved it; resisting a final judgment until more of their story can be told.

My job is not to judge Middlemarch; what a boring job that would be. Instead, I dream of the version of myself who commits to closely reading these strange, large, and sometimes boring books. I commit to becoming her with even more frequency.

I dream of the conversations we can have about even the most tedious of sections; and, each week, another reader on this journey with me sparks my mind alive with possibilities and reminds me why we do this. Why we take on projects like this one.

Eliot reminds me. Foucault reminds me. The people I’m reading with this summer remind me.

Why we read, why we keep reading, why it’s worth staying awake.

writes .

Your close read joins with my love of Eliot and Foucault and reminds of this quote from Milan Kindera in _Testaments Betrayed_: “Suspending moral judgment is not the immorality of the novel; it is its morality. The morality that stands against the ineradicable human habit of judging instantly, ceaselessly, and everyone; of judging before, and in the absence of, understanding.”

Thank you for joining us here with this terrific essay that got me rereading Eliot and thinking about all you've said here.

Thanks for contributing! I'm intrigued, but also puzzled by this distinction: "I have no interest in judgment, these days. Judgment is easy and often finite. It’s what Amanda Montell, in her book Cultish would call a “thought terminator.” After all, that’s what judgment is for: to make it unnecessary for there to be any further questions or ponderings on a given matter. Judging settles things. It puts ideas to rest.

But what of wakefulness? Of being eyes wide open inside a story? What of paying attention?"

I'm of two minds about judgment as it comes to reading. My literary hero is Willa Cather, and she loved the art she loved fiercely and despised the art she disliked just as passionately. Thea Kronborg, of The Song of the Lark, even describes "creative hate," which is a kind of detestation for mediocrity.

For me, there is no distinction between paying attention as a reader and making critical judgments about craft, ideas, aesthetics. When Steinbeck's narrator starts to make sweeping generalizations and drifts into moral hectoring in "East of Eden," I chafe at it. When his characters come alive, I thrill to them.

What do you see as the fundamental difference between judgment (or discernment) and wakefulness?