Dear Friends,

For my pieces on Inner Life, I’d like to explore a few ‘classic,’ ‘famous’ essays - pieces that get referenced a lot, but which are easy enough to have missed. If nothing else, these are an opportunity to revisit the original essay - in this case David Graeber’s ‘Bullshit Jobs’ piece from 2013 - and to get a flavor for what the author was originally saying, which, often, can be pretty different from how the ideas of the essay have been disseminated in the culture at large.

Best wishes,

Sam Kahn

ON ‘BULLSHIT JOBS’

I can actually remember where I was when I first read the ‘Bullshit Jobs’ essay. I was at work, surfing the web on a slow afternoon, not at all sure that the job I was doing made, in Graeber’s language, “a meaningful contribution to the world,” and read the essay and looked around and had the feeling of having caught the whole office out, of realizing that everybody else was exposed by the same embarrassing secret.

Graeber’s essay, as he describes it in its book-length elaboration, was “based on a hunch.” He had grown up - like all of us - surrounded by the dogma that capitalism might be cruel but it was also lean and mean and efficient. The profit principle was supposed to be so strong that, if nothing else, then everybody earned their keep.

But that didn’t quite seem to be what was happening if one did a quick once-over of their office, as I was doing, or if one allowed dinner party guests to get a few in them and then asked them if they thought there was any intrinsic value to their work - which seemed to be how Graeber conducted his research for the original ‘Bullshit Jobs’ article. It turned out that very few people were able to articulate what their job was or why it mattered. And, by the time of the book, when Graeber was able to draw upon some more sophisticated methods of polling, it turned out that about 37% of respondents in a British survey claimed that their job “made no meaningful contribution to the world” while 40% in a similar Dutch study said that “their jobs had no good reason to exist.”

Graeber is an anarchist, writing from a leftist perspective, and his conclusion, not so surprisingly, has to do with the dissolution of capitalism. “I would like this book to be an arrow aimed at the heart of our civilization,” he writes in the Bullshit Jobs introduction. “There is something very wrong with what we have made ourselves. We have become a civilization based on work - not even ‘productive work’ but work as an end and meaning in itself….It is as if we have collectively acquiesced to our own enslavement.”

Particularly in the original essay, Graeber’s focus is on a swathe of white-collar work, which he calls the ‘administrative sector’ and includes industries like financial services, corporate law, human resources, public relations. His analysis, which gets somewhat psychologically-oriented, is that there is such a thing as real work, which involves performing necessary tasks, being a nurse, garbage collector, subway train driver, etc; and then there is all the work that is basically extraneous. What’s particularly perverse, in Graeber’s view, is that the society is engaged in a sort of mass resentment of those whose work is actually significant. “Real, productive workers are relentlessly squeezed and exploited,” Graeber writes. “The larger stratum is basically paid to do nothing, in positions designed to make them identify with the perspectives and sensibilities of the ruling class - but, at the same time, foster a simmering resentment against anyone whose work has clear and undeniable social value.”

This is of course the language of class warfare - the belief that those who are doing real, productive work should come to consciousness and should, at the very least, get paid better than the wide swathe of white-collar bullshit jobs. That’s a valid-enough point, but Graeber goes off in two other directions that I am more interested in following at the moment.

One is the comparison that he keeps making between the United States, at its ostensibly capitalist apex, and the Soviet Union. Graeber writes:

In capitalism, this [the proliferation of bullshit jobs] is precisely what is not supposed to happen. Sure, in the old inefficient socialist states like the Soviet Union, where employment was considered both a right and a sacred duty, the system made up as many jobs as they had to (this is why in Soviet department stores it took three clerks to sell a piece of meat). But, of course, this is the sort of very problem market competition is supposed to fix. According to economic theory, at least, the last thing a profit-seeking firm is going to do is shell out money to workers they don’t really need to employ. Still, somehow, it happens.

Something about this really struck me and aligned with a hunch I’ve had - that there was always more in common between the Soviet system and the American imperium than might have been supposed. The ‘bullshit jobs’ observation catches something important - that American capitalism isn’t exactly the sort of cowboyish, let-the-chips-fall-where-they-may free market that we’ve been raised to believe it is. That it is a managed system. That there are society-wide goals, much as there were in, say, the USSR, that those goals include objectives like ‘full employment’ and often point in very different directions than what the ‘profit principle’ would seem to suggest. In my own office experience, the profusion of ‘bullshit jobs’ often seems to emerge from a sort of generous exuberance - companies early on deciding that they’re committed to ‘growing’ and then hiring freely, past their ability to guarantee any actual work. In some sense, this spirit of spread-the-work-around, if less than optimally efficient, is actually benevolent. I’ve noticed that above all in companies’ willingness to hire young people who know nothing and drain a salary and who may not stay around long enough to actually benefit the company - but the companies are willing to make the investment out of some commitment to the ‘long-term health’ of the industry. And, on a more macro level, that’s maybe a reasonable way to understand and to justify that 40% of the economy (if not more) that by its own assessment contributes nothing of discernible value but which does keep itself employed, keeps the wheels of commerce turning, etc.

But that’s a rosy way to spin the phenomenon Graeber is describing. And if the enforced employment of the Soviet Union was ultimately suffocating, injurious to the system as a whole, our variant of it may be as well. Graeber gets a bit apocalyptic in the language he uses to describe the system we have, but, at the same time, it’s hard to argue that he’s completely off in what he’s describing. He writes, for instance:

Once, when contemplating the apparently endless growth of administrative responsibilities in British academic departments, I came up with one possible vision of hell. Hell is a collection of individuals who are spending the bulk of their time working on a task they don’t like and are not especially good at. The moral and spiritual damage that comes from this situation is profound. It is a scar across our collective soul.

I had that sort of experience at the peak of the pandemic. I was working on a high-end production with high stakes - we all really wanted it to be good. But somehow the creative team was shrunken down to four people, and somehow, within a few months of working on the project, the production company was no longer willing to pay for hotel rooms on shoots and was encouraging the creatives to stay with relatives. This was not, however, because there was no money. There was money for lawyers and insurance risk assessment and liaisons from within the production company to deal with the lawyers and with the risk assessors. And then of course there were whole new Covid testing protocols - which had very, very little to do with reducing transmission but were really adept at limiting liability. The Graeber ‘bullshit jobs’ essay was a welcome guide to that experience, a terrific way of understanding what was happening - and it didn’t feel benevolent at all or a method to generate employment; it was all fear-based, a way of passing the risk around.

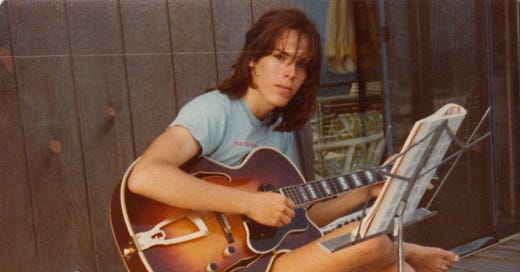

This is the other arresting direction that Graeber takes his argument in - contending that the bullshit jobs phenomenon isn’t really about jobs at all, or even the economy, it’s about what we do with our souls. In his essay he tells the paradigmatic story of a school friend, who had been a poet, an indie rocker, who was “brilliant, innovative,” and who had then, as he put it to Graeber, “taken the default choice of so many directionless folk: law school.” That story - so common, apparently so trivial - would usually be treated as a kind of parable of maturation, but for Graeber it’s symptomatic of everything that’s wrong with the culture. “What does it say about our society that it seems to generate an extremely limited demand for talented poet-musicians, but an apparently infinite demand for specialists in corporate law?” he writes.

Like so many critics, Graeber leaves things off before proposing any sort of solution. I don’t think he has any suggestions for how to generate demand for poet-musicians - and neither do I. But at least the terms of the problem are being clearly set out. What we’re interested in, Graeber would suggest (and I would agree), isn’t the society of full-employment or the society of benevolent corporate largesse. What we want is a society in which as many people as possible can do what they love to do. A society with dignity in work and recognition for work well done. The social project is about enabling that, however it can.

Sam Kahn writes Castalia.

Sam, What a fab way to open our posting weeks with guests on Fridays: Hurrah! We already have a line-up on the arts in the broadest sense—and that means folks working hard in this difficult world where it’s hard to make a living. Having done my “time,” so to speak, in corporate America before I could afford to write fiction and memoir and teach again, I so get this. I’ve been trying to line up two Substack-ers doing great work and whether I get them or not, I want to give shoutouts to https://austenconnection.substack.com (still hoping, Jane!--write me!) and https://dadadrummer.substack.com. ~ Mary @ mltabor@me.com

This lines up rather well with my disillusionment with academe, which is supposed to be one of those places of refuge for poet-musicians and other idealists, but which more often resembles something like a factory. This owes in part to the tenure system, a 4-6 year window in which an academic feverishly strives to demonstrate their worth by publishing little-read essays in niche journals, serving on committees, and trying to toe the line between acceptable rigor and pleasing a student audience not much interested in intellectual rigor. The sheer scale of writing produced by the tenure system vastly outpaces any demand from readers. If you are lucky, you stumble upon a research agenda that you find personally meaningful and that attracts a following, of sorts. But there is a good deal of work produced by the publish-or-perish imperative that is never meaningfully consumed. Even some of the work that manages to get cited is poorly read -- indexed through or mined for a salient line or two rather than absorbed in the way that true reading requires. And, as in book publishing, there is an enormous degree of gatekeeping that conspires against anyone who is not either born into privilege or ushered through the gate after attracting the favor of a powerful person (see Tara Westover).

In the proper arrangement, one's burning research questions line up with one's teaching, and the whole arrangement complements itself. The life of the mind -- the spirit of this collaborative -- is answer enough to why the work matters to all involved. But the more one looks to college for particular skills, and the more one demands a predictable return on investment, the more bullshit the job becomes from the faculty side, at least in many non-applied disciplines. At this point the question of why the work matters to faculty is often thoroughly divorced from why academic teaching matters to students. Faculty are then often placed the position of endlessly justifying work that they initially found instinctually and inherently meaningful, while those tasked with the ever-ballooning raft of administrative duties are rarely required to justify their work. Hence my comparison last year of academe to Communist-occupied Czechoslovakia.

The sad fact about this is that those of us who chose academe initially were explicitly trying to avoid bullshit jobs. In my case, the immediate choice was between a permanent position in fire suppression with the Forest Service (which I knew would be a desk job with endless Environmental Impact Statements, etc, and nothing like the seasonal field work that I still remember fondly) and graduate school in literature. I had lost faith in the philosophy of fire suppression, having personally snuffed many a lightning strike that ought to have been allowed to burn for the health of the forest, but that was only extinguished to protect merchantable timber. One of my USFS supervisors had a poster in his office that read, "Occupants are lifers with nothing left to lose." How sad, yet darkly funny, that the same could be said for many mid-career or late-career academics, who have also lost faith in the master narratives that drive their enterprise.