“I have had a bad time of it lately,” wrote W.B. Yeats to Lady Gregory on April 24, 1900. He was bringing his patron up to date on a rebellion he was leading within the secret society of occultists to which he belonged, the Order of the Golden Dawn. “I told you I was putting Macgregor out of the Kabbala,” he reminded her—Macgregor being the recently ousted chief of the order, S.L. MacGregor Mathers, and “the Kabbala” Yeats’s self-mocking term for the order itself (he called his fellow members Kabbalists, at least when writing to Lady Gregory). “Well, last week,” he went on, “[Mathers] sent a mad person—whom we had refused to initiate—to take possession of the rooms and papers of the Society.” The person in question broke into the Golden Dawn temple in London, changed the locks, and sent out messages summoning high-ranking members to face questioning there in three days’ time. On the appointed day, he returned “wearing a black mask and in full highland costume and with a gilt dagger at his side,” only to be stopped by the intervention of the landlord and driven off by Yeats and another member with the help of a constable. Having failed by such means to lay claim to the premises, this individual was now asserting a legal right to them on the grounds that he had been designated to do so by Mathers—who, he argued, remained the order’s rightful head. “The envoy,” Yeats added, “is really one Crowley, a quite unspeakable person. He is I believe seeking vengeance for our refusal to initiate him. We did not admit him because we did not think a mystical society was intended to be a reformatory. Mathers like all despots must have a favorite and this is the lad.”

The dispute was soon settled, leaving Yeats and his associates in charge of the London temple and its property. What I would like to discuss is the past grievance referred to here: the decision to keep a 24-year-old Aleister Crowley out of the order’s elite ranks.

Crowley has a sinister reputation (of which he himself was a tireless promoter), and most commentators have sided against Mathers for supporting his membership. Certainly, Crowley’s scandalous exploits are not to everyone’s taste. But the main conduct at issue here is in fact unobjectionable to modern sensibilities, and if a mystical society was not intended to be a reformatory, Mathers—for one—insisted that neither was it meant to be an Edwardian social club.

Edward Alexander Crowley was born into a wealthy middle-class family, heir to a fortune made in brewing and railroads. His parents belonged to a millenarian Christian sect, the Plymouth Brethren. In 1895, he went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, where for the first time he was free of his strict religious upbringing. There, dropping his first name and adopting the Gaelic form of his middle name under the influence of the fashionable Celtic Revival, he became Aleister Crowley.

Eighteen ninety-five was also the year in which Oscar Wilde was convicted of “gross indecency” and sentenced to two years’ hard labor. The case had a chilling effect on public expression of same-sex desire at just the time when Crowley, on Christmas break in Stockholm in the middle of his second year, discovered that the scope of his robust sexual appetite included a taste for being penetrated by other men.

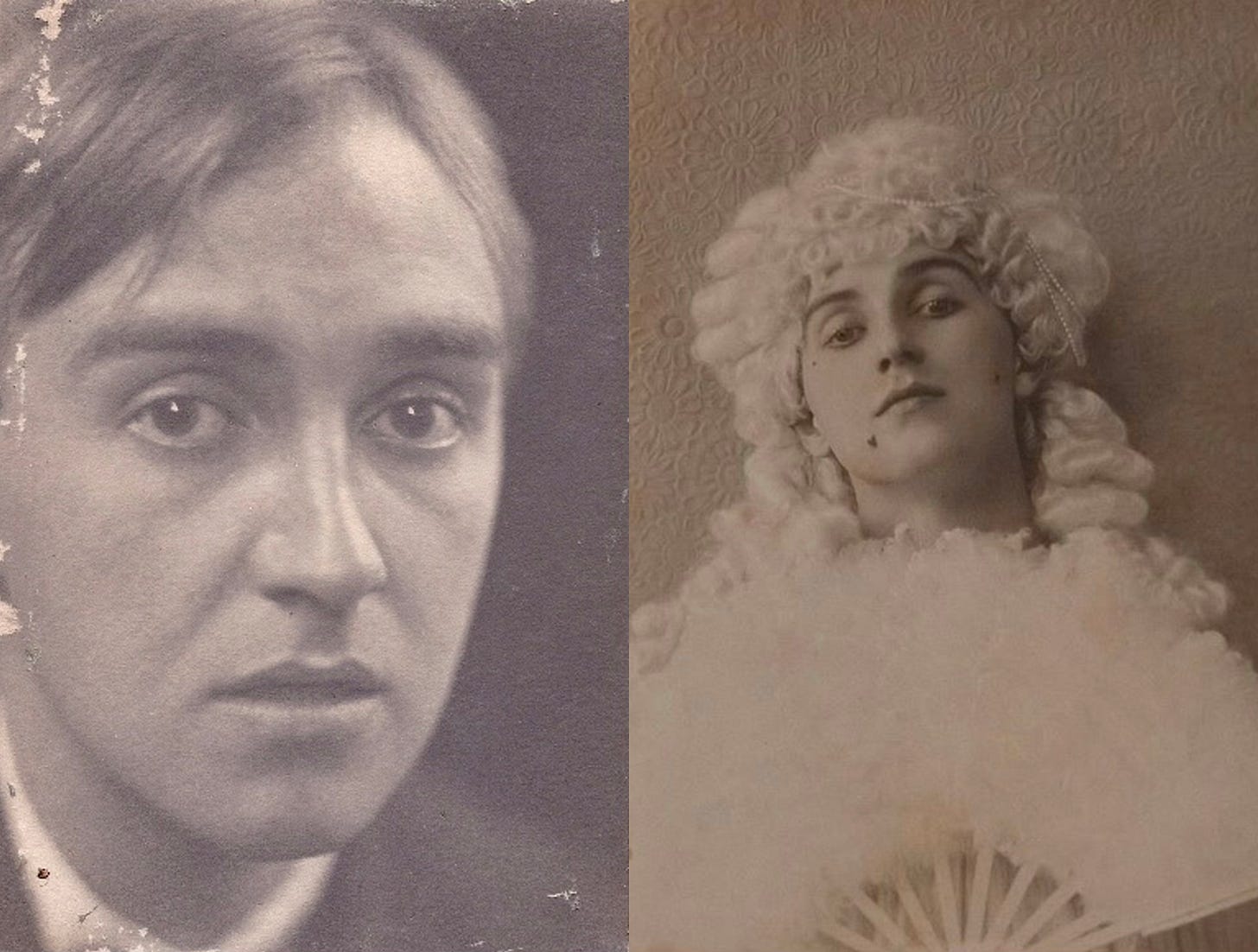

In October 1897, he met Herbert Charles Pollitt, the well-to-do son of the owner of the Westmorland Gazette. A Cambridge man with a master’s degree, Pollitt had returned to dance as a female impersonator for the university’s Footlights Dramatic Club under the billing of Diane de Rougy. “The grossness of people who do not understand art naturally misinterpreted this aesthetic gesture and connected it to a tendency to androgynity,” Crowley would later complain. “I never saw the slightest symptoms of anything of the kind in him; though the subject sometimes came under discussion.”

His new friend introduced him “to the actual atmosphere of current aesthetic ideas, to the work of Whistler, Rops and Beardsley in art, and that of the so-called decadents in literature”—and even to Beardsley himself, a friend of Pollitt’s then dying of consumption. As to the nature of their relations, Crowley describes them in his autobiography as “that ideal intimacy which the Greeks considered the greatest glory of manhood,” deploring the fact that in England “such ideas are connected in the minds of practically every one with physical passion.” A notation in his personal copy of the book is more candid: “I lived with Pollitt as his wife for some six months and he made a poet out of me.”

That period came to an end in the summer of 1898, when the two men went away to the Lake District. On the trip, Crowley, to his deep regret, found himself growing more and more estranged from his companion, who had no interest in either mountain climbing or Crowley’s latest passion: mysticism. He was then reading Karl von Eckartshausen’s Cloud Upon the Sanctuary and dreaming of joining “a secret community of saints in possession of every spiritual grace, of the keys to the treasures of nature, and of moral emancipation such that there was no intolerance or unkindness.” This joyful aspiration stood in contrast to Pollitt’s typically Decadent “acquiescence in despair of the universe.”

Crowley felt he had to make a choice. Finally, he went off without telling Pollitt. The latter discovered where he was and turned up at the inn. There was an ugly scene in which, in Crowley’s words, “I told him frankly and firmly that I had given my life to religion and that he did not fit into the scheme.” They never spoke again.

Later that summer, while mountaineering in the Alps, Crowley met a man named Julian Baker, an analytical chemist living in London who in his spare time experimented in alchemy. When Crowley told him of his hope to find a “Secret Sanctuary of the Saints,” Baker, a member of the Golden Dawn, hinted that he knew of such an assembly. He promised when they met again in London to introduce Crowley to a man who was “more of a Magician” than himself.

Having abandoned Cambridge without a degree, Crowley went on to London, where he composed Jephthah, a verse tragedy with lines like these:

“Now let me die, at last desired, At last beloved of thee my queen. Now let me die, with blood attired, Thy servant naked and obscene; To thy white skull, thy palms, thy feet, Clinging, dead, infamous, complete.”

Jephthah, and Other Mysteries Lyrical and Dramatic came out the following year. Crowley brought the printer’s proof with him one evening when he went to call on Yeats, perhaps at one of the poet’s regular Mondays at home. The latter, ten years his senior, had lately published his third collection, The Wind Among the Reeds. Crowley showed him his own book and, as he tells it, Yeats

forced himself to utter a few polite conventionalities, but I could see what the truth of the matter was. It would have been a very dull person indeed who failed to recognize the black, bilious rage that shook him to the soul. What hurt him was the knowledge of his own incomparable inferiority.

It would indeed be a very dull person who failed to detect Crowley’s own distress on the occasion or recognize its source. Yeats was not just a genuine poet but a genuine Irishman, while Crowley was left to self-publish his Swinburnian pastiches and vainly speculate he descended from the O’Crowleys.

Baker, back in London, kept his promise. Crowley was invited to meet the man Baker considered a superior magician—fellow Golden Dawn member George Cecil Jones—and in time to join the order himself. He took the affair, as he writes, with “absolute seriousness,” even asking Baker on the eve of his initiation “whether people often died during the ceremony.”

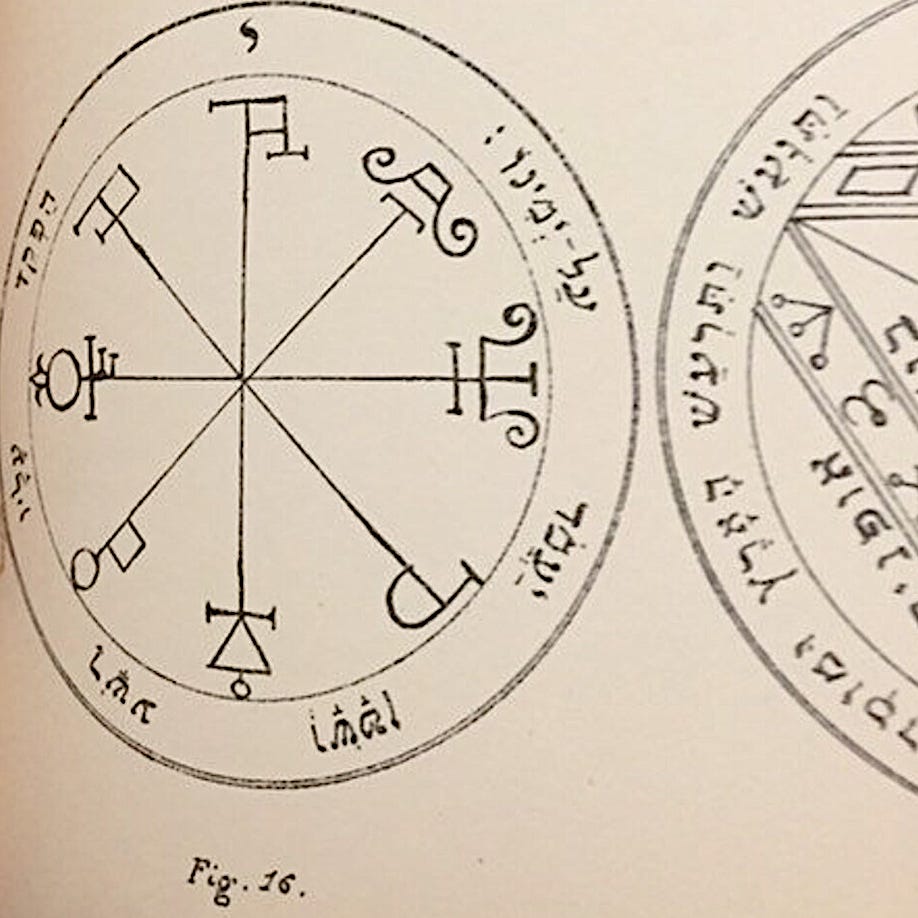

These hopes and fears would prove excessive. Having taken a solemn oath not to reveal what he was shown at pain of receiving “a deadly and hostile current of will,” he discovered that the dread secrets he was vouchsafed “consisted of the Hebrew alphabet, the names of the planets with their attribution to the days of the week, and the ten Sephiroth of the Cabbala,” information already familiar to him and moreover readily available in published sources. He confided his doubts in Baker and Jones, who, as he writes, “insisted, rightly enough, that I was not in a position to judge the circumstances. I must first reach the Second Order.” It was in the elite Second—or Inner—Order, whose proceedings were veiled from those below, that members were entrusted with the most prized secrets in the society’s possession, including instructions for performing magical operations.

So Crowley determined to reach the Second Order. His path was clear. The Golden Dawn resembled a school of occultism. In the course of their studies, members passed examinations and progressed through a series of grades. Crowley, a trained scholar, advanced with ease. By the following May, he had taken all four grades of the society’s First Order. He was required to wait seven months before he would be eligible to apply to the Second Order, and then only if invited.

In the meantime, he went to visit the Chief Adept of the order, who was living in Paris. He was eager to do so, having read with great interest Mathers’ translations of little-known medieval occult works. His host received him warmly. While it was only to be expected that the vain and impecunious Mathers would take a liking to this rich young admirer, the affinity between the two men was real enough. Like Crowley, Mathers had changed his name out of a fanciful sense of kinship with the Celtic peoples. Born in Hackney to a family with no connection to Scotland, he had nevertheless adopted the surname MacGregor and even assumed the noble title Count of Glenstrae.

Crowley—who then happened to be renting a London flat under the name Count Vladimir Svareff—started signing letters Aleister MacGregor in imitation of his chief. That fall, he took a vacation to the Highlands and wound up buying himself a manor on the shore of Loch Ness, where he started dressing in a kilt of MacGregor tartan and calling himself the Laird of Boleskine.

Once settled, he applied to the Second Order on Mathers’ invitation. The London temple declined to admit him without saying why. He wrote to Mathers, who told him to come to Paris, where on January 24, 1900, Crowley was initiated into the Second Order by the Chief Adept himself.

At the time, Crowley had other things on his mind than spiritual advancement. On his way to Paris, he had stopped in London for a few days and there received a warning from a woman he knew: he and some friends living at his former address in town—with whom he may have been sexually involved—were being watched by police, a state of affairs said to be “connected with ‘the brother of an old college chum.’” “No doubt can be entertained of the meaning of her hints,” Crowley noted in his diary. He had, in other words, reason to believe himself under official surveillance on suspicion of criminal sodomy due to a complaint filed by Pollitt’s family. Before the day was over, he caught the night boat to Paris.

After his initiation, Crowley asked Mathers for guidance concerning his trouble with the law. The chief looked at Crowley’s astrological chart for the hour at which the information had reached him and declared, “The news is true but you are very strong and the end of the matter is good.” Crowley was nevertheless advised to avoid London. On his way home, he stopped in Cambridge, where another associate confirmed he was “wanted.”

Once back in Scotland, Crowley wrote to ask the London temple for the teachings to which, as a member of the Second Order, he was now entitled. At the end of March, he got word that the leadership did not recognize his initiation by Mathers. Realizing this amounted to a revolt against the Chief Adept, he sent a message to Mathers “offering to place [himself] and [his] fortunes unreservedly at [Mathers’s] disposal.” The sequel has been told above.

Crowley was never given any official justification for his refusal by the Second Order. He did, however, get an explanation from an ally within the organization, a Mrs. Alice Simpson. She informed him, as he recorded in his diary, that he stood accused of “sex intemperance in order to gain magical power—both sexes are here connoted!” In fact, it would be some years before Crowley took up sex magic, but the gravamen here, in any case, is surely the “both sexes” part.

Rumors about Crowley’s sexuality had reached the Second Order. Yeats alludes to such suspicions in the letter quoted above. The line “Mathers like all despots must have a favorite and this is the lad,” for example, evokes relationships like those between Edward II and Piers Gaveston or Charles I and Buckingham to hint at Crowley’s deviant tendencies. Just as telling is the fact that no fewer than five times in three letters sent that week does Yeats make use with reference to Crowley of the contemptuous epithet “unspeakable,” calling him in one instance “a person of unspeakable life.” In the period, the innuendo would be no more liable to be missed than that of Lord Alfred Douglas’s well-known phrase “the love that dare not speak its name,” and the remark about Crowley’s belonging in a reformatory bears the same implication.

While homosexual activity was almost certainly the principal charge against Crowley, it was not, to be fair, the only one. Aside from his encounters with men, there were his probably more numerous ones with women (though Yeats himself had his liaisons). And then there was his drug use (though Yeats wrote an essay on the visionary effects of hashish and experimented with mescaline), not to mention his false names and some bad debts.

Mathers, for his part, was willing to overlook all that, and not merely out of a taste for flattery or the hope of financial support. He had long insisted his followers abide by a precept of fraternal love and mutual acceptance—the very “moral emancipation” Crowley had been seeking. Back in 1896, in reaction to a spate of challenges to his authority over similar questions, Mathers had issued a formal manifesto in which he avowed:

What I discountenance and will check and punish whenever I find it in the Order is any attempt to criticise and interfere with the private life of Members of the Order; neither will I give the Wisdom of the Gods to those who endeavour to use it as a means of justifying intolerance, intermeddling, and malicious self conceit. The private Life of a Person is a matter between himself or herself, and his, or her God.

In the temples of the order where initiates to the mysteries invoked the divine light, he added, “the petty criticisms and uncharitableness of social clubs and drawing rooms” had no place.

Nor was Mathers alone in holding such principles. They were, in fact, Golden Dawn orthodoxy. A series of papers setting forth the order’s higher doctrines included one titled “Secrecy and Hermetic Love,” whose author—the high-ranking member Florence Farr—advocated tolerance of others and questioning of social conventions:

Free yourselves from your environments. Believe nothing without weighing and considering it for yourselves; what is true for one of us, may be utterly false for another. The god who will judge you at the day of reckoning is the God who is within us now; the man or woman who would lead you this way or that, will not be there to take the responsibility off your shoulders….

Therefore brotherly love does not imply seeking, or remaining in the society of those to whom we have an involuntary natural repulsion. But it does mean this, that we should learn to look at people’s actions from their point of view, that we should sympathise with and make allowances for their temptations. I would then define Hermetic or Brotherly Love as the capacity of understanding another’s motives and sympathising with his weaknesses, and remember—that it is generally the unhappy who sin.

Farr herself knew what it meant to face social judgment. A divorced, freethinking, sexually liberated actress living independently on a modest private income, she was a turn-of the-century “New Woman” par excellence. She was, moreover, a friend of Wilde’s and in 1905 staged the first performance in England of his infamous play Salomé. Her advanced opinions found expression in a popular series of essays for The New Age, a leading socialist weekly to which Shaw, Wells, Bennett, and even Chesterton regularly contributed. In one especially controversial article, she argued that “until women have as good a chance of making independent incomes as men, we must divide women into two classes: those whom men pay to raise them heirs and those whom men pay to give them pleasure.” Things being so arranged, she concluded, it would be better to emulate the ancient East, where prostitutes were not made a degraded class but carried out their occupation as a sacred institution.

That Mathers practiced the permissiveness he taught is shown by the fact that, at the time of the events related above, Farr was—after himself—the order’s top leader, holding the title Chief Adept in Anglia. As such, she was in charge of the Second Order in London when Crowley was turned down. It is worth asking, then, how well she applied her own principles with regard to his case.

If Farr was to blame for Crowley’s rejection, it is curious that Crowley himself does not seem to have held her responsible. In his autobiography, he describes her as a “charming and intelligent woman… for whom I always felt an affectionate respect tempered by a feeling of compassion that her abilities were so inferior to her aspirations.” A somewhat backhanded compliment, to be sure, but one that nevertheless stands in contrast to his assessment of the great majority of Golden Dawn members, who are dismissed in his autobiography as “muddled middle-class mediocrities” or worse. Crowley was not one to turn the other cheek. Had she been an enemy, Farr would have been treated no better than his arch-nemesis in the order, Yeats, who is called “a lank dishevelled demonologist who might have taken more pains with his personal appearance without incurring the reproach of dandyism.”

In fact, Farr was one of a handful of friends Crowley made in his time in the First Order (and if gossip is to be credited, the two were more than just friends). Along with Jones and Baker, she was one of three intimates whose counsel he went to London to seek while waiting to hear back from Mathers about his offer to help put down the insurrection. Crowley writes that Farr, “the nominal representative of the Chief, was trying to find a diplomatic solution” to the crisis, adding, “Her attitude was most serious and earnest and she was greatly distressed by her dilemma.”

Though they found themselves on opposite sides of the rebellion against Mathers, which Farr co-led with Yeats, neither seems to have lost respect for the other. Farr’s sympathy for Crowley is shown beyond doubt in a review of his work that appeared in The New Age some seven years later. “It requires a certain amount of serious purpose to stir Public Opinion into active opposition,” she wrote,

and the only question is, has Mr. Crowley a serious purpose? Our first instinctive feeling is that “It is damned clever, but it won’t do.” That is succeeded by the certainty that “It is raving madness”; and a final judgment that the young man is a remarkable product of an unremarkable age.

Though her praise is not unqualified and the review was unsigned, Crowley was nonetheless moved by the support. “I was enormously encouraged by this article,” he recalled in his Confessions, where he quoted the more laudatory passages at length. “She had reassured me on the point where my faith wavered.”

For many years after his first warning of sodomy charges, Crowley remained in serious jeopardy. On at least two occasions, the allegations against him had real legal consequences. The lawsuit filed by Crowley (in the name of Edward Aleister) over the properties of the London temple was put a stop to, according to the little-known account of a key witness, by raising threats of a criminal prosecution: “He withdrew his case by the advice of his solicitor who was informed that the police had matters against Crowley, whom he advised to leave the country at once.” Crowley was forced to settle and pay £5 (£500 today) in costs, after which he in fact went abroad, not to return for nearly two years.

And in 1911, his old friend Jones brought a libel suit against a newspaper that had linked him to Crowley, who in turn was accused of unnatural vice. Crowley himself did not sue—thus avoiding the fate of Wilde, who had been arrested on criminal charges after losing a suit intended to clear his name. He did, however, voluntarily attend both days of the trial despite the danger to his freedom should he be called to the witness stand. Though Crowley was not a party to the case, all the testimony concerned him and his scandals. The defense’s closing argument was simple: “Were we not justified in saying that you must judge this man’s character by his association with this creature?” In the end, Jones, whose own behavior was not directly at issue, lost the case and was made liable for court costs.

In the aftermath, Crowley was deserted by many longtime friends and followers, including Jones and Capt. J.F.C. Fuller, his last and most influential supporter within the British establishment. The process, begun at Cambridge, of his radical alienation from respectable society—in which his sexuality played a decisive and often forgotten role—was complete. By this time, the Edwardian age was over, and Crowley was proclaiming the Aeon of Horus.

Alan Horn writes The Invisible Head.

Fascinating read. I feel like this ended on a cliff hanger. Is there going to be a part 2?

Didn't know any of this: a story of unfairness. Thank you for joining us here, Alan.