The Footnote

When did you first meet the footnote and did it lead to love?

I’m not betting on love between you and the footnote.*

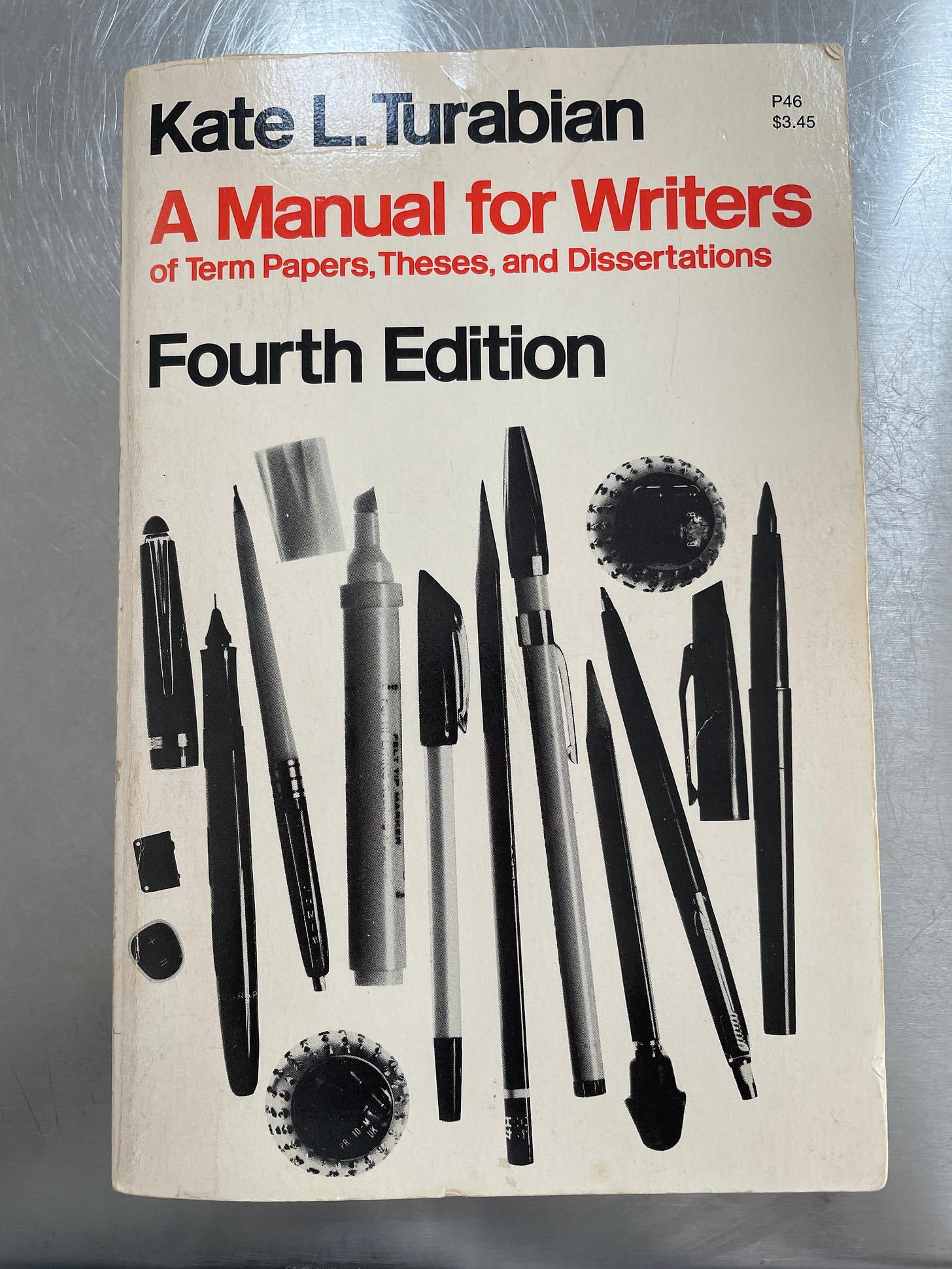

As to when, I’m betting it was in high school or college when some good teacher handed you A Manual for Writers by Kate L. Turabian, sent you off to write your first term paper and learn to hate the footnote.** Some of you at the thought of ever having to write another footnote, or worse, read one! may want to scream “the horror! the horror!”, Kurtz’s last words in The Heart of Darkness and have that be the end of it. I don’t blame you.

But I have a different story to tell you:

I love the footnote, not because I’m so good at writing one, but because the not-so-important tag at the bottom of the page, the back of the chapter, the end of the book has always been a beginning for me.

I first encountered the footnote at my father’s side in synagogue. While he davened, the Hebrew word for prayed, I read footnotes. He wasn’t big on prayer. He was reciting Hebrew prayers he knew by heart, could read but not translate: the way he was taught. I was about eight years old and would be reading the big blue book I’d pulled from the book slot in front of me: The Torah, the first five books of the Bible. The rabbis’ comments are in the footnotes. This is where I learned what to take literally, what to read differently. The rabbis’ questions after questions about passages discussed endlessly and read all year long and then started over once again the following year landed in the footnote. I read about skins and feathers in Leviticus, about Miriam, my Hebrew name, in Exodus and Rabbi Rashi’s view that she was a prophet before Moses’s birth. My parents named me after someone that important? I got scared. My father consoled.

My father admired. And my love of the footnote got hooked to my love for him. He’s the shadow behind the man I love.

He loved that answer-a-question-with-a-question stuff. He died more than a decade ago and I miss him.

And then I found him in a footnote. I was reading Auden’s essays Forewards & Afterwords and got stopped in my tracks by his footnote that compared the Socratic dialectic, aka answer-a-question-with-a-question, to free association in psychoanalysis. He’s talking about curiosity, inquiry and asserting, yes, in a footnote, that we gotta, as in Nike’s logo, Just do it! ourselves.

And there I was on the metaphorical couch: Recalling my father. His questions. Here’s one he asked me when I was ten: So, Mary, you’re ten. Would it be enough if Moses wrote the famous ten? He meant, Instead of the miracle atop the mountain.

He was asking me to think. I was learning about love: the love a parent gives a child, the love that forms our ability to love another.

Oh, let’s digress back to Moses. I’m still thinking about my father’s question after all these years. Here’s my answer: Moses did have to go up that mountain twice. He smashed the tablets the first time he came down. Did he really go back up and say, Hey, big guy, could you do it again for me?

My father’s love for me was like music. Leonard Bernstein said about music, “It doesn’t have to pass through the censor of the brain before it can reach the heart … An F-sharp doesn’t have to be considered in the mind; it is a direct hit.”

I grew up in a Baltimore row house with stairs to the second floor and stairs to the basement and a view from the front door to the back door and the clothes tree outside the door. My childhood house didn’t have hallways or a foyer. There was no place to hide anything or to hide. I could hear the neighbors when they argued and everything that everyone said inside my narrow house was fair game for anyone in the back, the front, up or down the stairs.

In that narrow house my father listened to opera on 78 RPMs in the basement. He never saw an opera live when he was young and vigorous. When he was old, after my mother died—she was not a fan of the music from the bottom of the stairs and he wouldn’t have gone without her—I could afford good seats to Madam Butterfly and took him.

When I lived in D.C., I went to the Kennedy Center to see and hear Puccini’s Tosca. When Tenor Frank Poretta sang the famous aria “E lucevan le stelle” in the last act, I heard the footnote of my father’s music rise up from our basement stairs.

The tenor sings of love.

Here's Placido Domingo singing the aria and who directed and was the conductor for the performance I saw:

The love of my life was at my side at the opera. I met him writing footnotes for what we termed “The Red Book.”

Not Carl Jung’s tome that I do own, but a treatise on energy from a think tank where I once worked. The man I loved was in charge of “The Red Book.” I was the editor assigned to write the footnotes, all 164 of them. He made me feel worthy while I did a task that was anything but central.

I was the footnote who mattered to him.

The tenor in Tosca sings of love in that final stirring aria in Act III. But it is not the words that move, it’s the melody that strikes the heart, brought me to tears, and reminded me that love and logic and worth were intertwined in my youth — and reminded me of this:

My father’s love was a direct hit.**

Be sure to read the footnotes:

________________________

*For haters of the footnote, David Shields wrote Reality Hunger, a marvelous book about his notes and notes of others about creativity and the making of fiction that hits the heart. He chose initially to use no footnotes for his quotes. The publisher said essentially, ‘No way’—so what he did was annotate with only the author’s name, occasionally the title of the work, but no exact citation, and he chose not annotate any of his own notes. After the book was published he went on—click to watch ➡️ The Colbert Report —to talk about what he did.

After reading the book and using it while teaching creative writing at GWU, I wrote Shields and here is our exchange:

“This book is breakthrough prose of the highest order. If you write (or if you read!) and haven't bought Reality Hunger, do! It's brilliant—the best work I've read on the writing process, on the nature of invention, on art and on the torturous permissions process that any writer who simply chooses to acknowledge and quote her influences—the writers who have been part and parcel of her thinking—that I have read in a lifetime of reading.”

And here is his reply:

“Thank you --for your post, which captures the book for me better than a hundred reviews. Yours, David”

**Mark R. DeLong, who restacked on Substack Notes my Dana Gioia interview with a comment about footnotes and then wrote me a personal email, I quote here with his permission: “I recall using footnotes as shields and swords myself when I was in grad school, and from what I can tell they do often seem like a defense among scholars. I'd even say they are almost a barometer of scholarly insecurity sometimes -- an insecurity betrayed by a pile of items. ‘Things I read, so you know I know.’ That's a feeling called up by the torments of study.

“I recall one time meeting with a professor who told me that a paper looked like it needed to be read with bifocals -- the text itself (dry and dismal, I admit) and the footnotes with my thoughts and sometimes snide remarks. She wanted me to bulldoze the footnotes into the body of the piece, and she was probably right.”

***Ibid in a footnote means the same source. I love my husband: Ibid to my father.

Mary Tabor writes

Two memories. One from the Best American Poetry anthology (forget which year) of a poem written entirely AS footnotes. Struck me as silly and experimental for the sake of looking audacious, but I should have read it more closely and now wish I had.

I first became aware of footnotes, however, in a less-than-positive way after my father received an annotated collection of Doyle's Sherlock Holmes. He read aloud to the family some evenings and started to do so from the new volume. But I suspect that he had/has an undiagnosed case of OCD, because he intended to interrupt the story by reading every footnote when it appeared, until we howled in protest. I suppose I've always had it in for footnotes as a result, but you've given good reasons to think again.

First fell in love with footnotes while reading Infinite Jest. (Yes, I am THAT lit-bro.) House of Leaves used them creatively too. Those two books wouldn't've been nearly as entertaining to read without them.