Why? in the face of moral ambiguity?

Before I begin, I introduce my next guest Elizabeth Bobrick who writes

Why Make Art?

Why make art, something “other” when faced with the dilemmas of existence, with, as I’ve said in one of my short stories, “all the ways that life betrays the living”?

I ask this not from the perspective of a philosopher, but from that of a writer of fiction and literary memoir and my own search for a moral framework—for a narrative of hope.

In my memoir (Re)Making Love, for better or worse, I found myself turning again and again to Friedrich Nietzsche’s works—along paradoxically and laughably too! with a bunch of rom-coms—believe it or not.

The draw to him was inexorable.

He questioned the foundation of the moral thought that preceded him. He did it big-time with his oft-quoted assertion, given to the madman: “‘Whither is God,’ he cried. ‘I shall tell you. We have killed him—you and I. … God is dead.’”[i]

I quote him, not as a non-believer, but as a searcher.

Nietzsche again: “‘[W]ill to truth’ does not mean ‘I will not let myself be deceived’ but—there is no choice—‘I will not deceive, not even myself’: and with this we are on the ground of morality.”

Nietzsche’s questioning resonates for me because he asks, Is a coherent narrative for our lives possible? And if we’ve got no clear answer, what then?

Just for the heck of it, let’s go back to the “royalty” of the canon: Kafka, Woolf, Joyce.

All reflect on the philosophical struggle that comprises the loss of coherence.

They write and, in doing so, perhaps they answer.

As to what I call ‘moral ambiguity’, here’s some critics who argue the modernist writer (Woolf, Joyce) moved inward and away from society. Yep, here I go with some research (bear with me):

The critic Peter Faulkner argues that “modernist writers fail to see man socially and historically, and so make his alienation, which is a social process, into an absolute.”[ii]

The critic Randall Stevenson argues, “Once narrative places ‘everything in the mind’, a sense of significance can be restored to individuals: it becomes once again possible to consider ‘what a terrific thing a person is’—regardless of how diminished … their actual lives in the modern industrial world may be.”[iii]

The critic Stephen Spender starkly expresses the issue: “In the works of the most characteristically modern writers contemporary civilization was represented as chaotic, decadent, on the point of collapse, anarchic, absurd, the desert of non-values.”[iv]

I don’t agree with Spender’s view as it relates to Woolf and Joyce, but I think he’s right about where Kafka leads us, as I cast back to him. Kafka, most certainly was an adherent of Nietzsche.

The critic Gerhard Kurz notes the importance of Nietzsche to Kafka: “The study of Kafka’s relation to Nietzsche was long obstructed by Max Brod’s [friend, biographer and literary executor of Kafka’s body of work] denial of such an influence. The relation first came to light in 1954, when Erich Heller named Nietzsche as Kafka’s ‘intellectual predecessor.’ [Kurz explains that Kafka met Nietzsche through his friend Oskar Pollak.].” Kurz asserts, “Kafka remained faithful to Nietzsche’s thinking until death.”[v]

Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathrustra is referenced three times by Joyce in Ulysses, showing, at the very least, that Joyce had read Nietzsche.

We know that Woolf read Joyce, with mixed commentary.

The dilemma you and I face and that Woolf, Joyce—and Kafka address is: How to decide what we ought to do when alone, separated from society, and believe society may not offer a set of shared values that work.

Virginia Woolf in her essay “On Being Ill,” said, “Human beings do not go hand in hand the whole stretch of the way. … Here we go alone, and like it better so.”[vi]

In To the Lighthouse, Mrs. Ramsay looks out on the constant stroke of the Lighthouse and says inside her head, “It will end, it will end.” She addresses the question of existence and asks herself, “What did it all mean? To this day she had no notion.” The novel’s middle section, “Time Passes,” separates the action of the novel and all the characters from society. The inexorable power of time and nature rule in “this silence, this indifference, this integrity, the thud of something falling”, and, in this context, three deaths occur in brackets: Mrs. Ramsay, rather suddenly; her daughter Prue Ramsay, in childbirth; her son Andrew, in the war.

In Ulysses, both Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus are exiles. Bloom is an outsider, a Jew, cuckolded by his wife, shunned by others, the object of derision and anti-Semitism. Stephen, recently returned from Paris, is the loner, struggling with refusal to take the sacraments, with his art, with his dissatisfaction with the politics of Ireland. It’s Stephen who says, “That is God. ... A shout in the street.”

K. in The Trial is the most cut off from the world. The novel opens with K. excluded from society by the accusation of guilt. We find no actual events in the novel. The Trial takes place devoid of time or place.

The movement to the self was perhaps inevitable and technique followed: Interior monologue and what came to be known in Joyce’s work as stream of consciousness that arose from a philosophic need to move narrative inside the domain of the “self.”

Ulysses intimidates readers because of its lack of clear narrative thread—though I argue we always know what day it is and what time it is. Those who dismiss the novel argue fairly, I think, that Joyce purposely impedes a clear linear narrative thread.

I argue that Joyce questions how one finds the narrative of one’s own life.

This question is bleakly explored in Kafka’s The Trial, where the move to the interior is extreme. Kafka doesn’t allow the reader to know for sure we are inside someone’s consciousness. K.’s seemingly impossible world could be the “real” world.

What faces us is the struggle to find meaning in the face of Nietzsche’s “undeceived” morality, a nothingness, if you will.

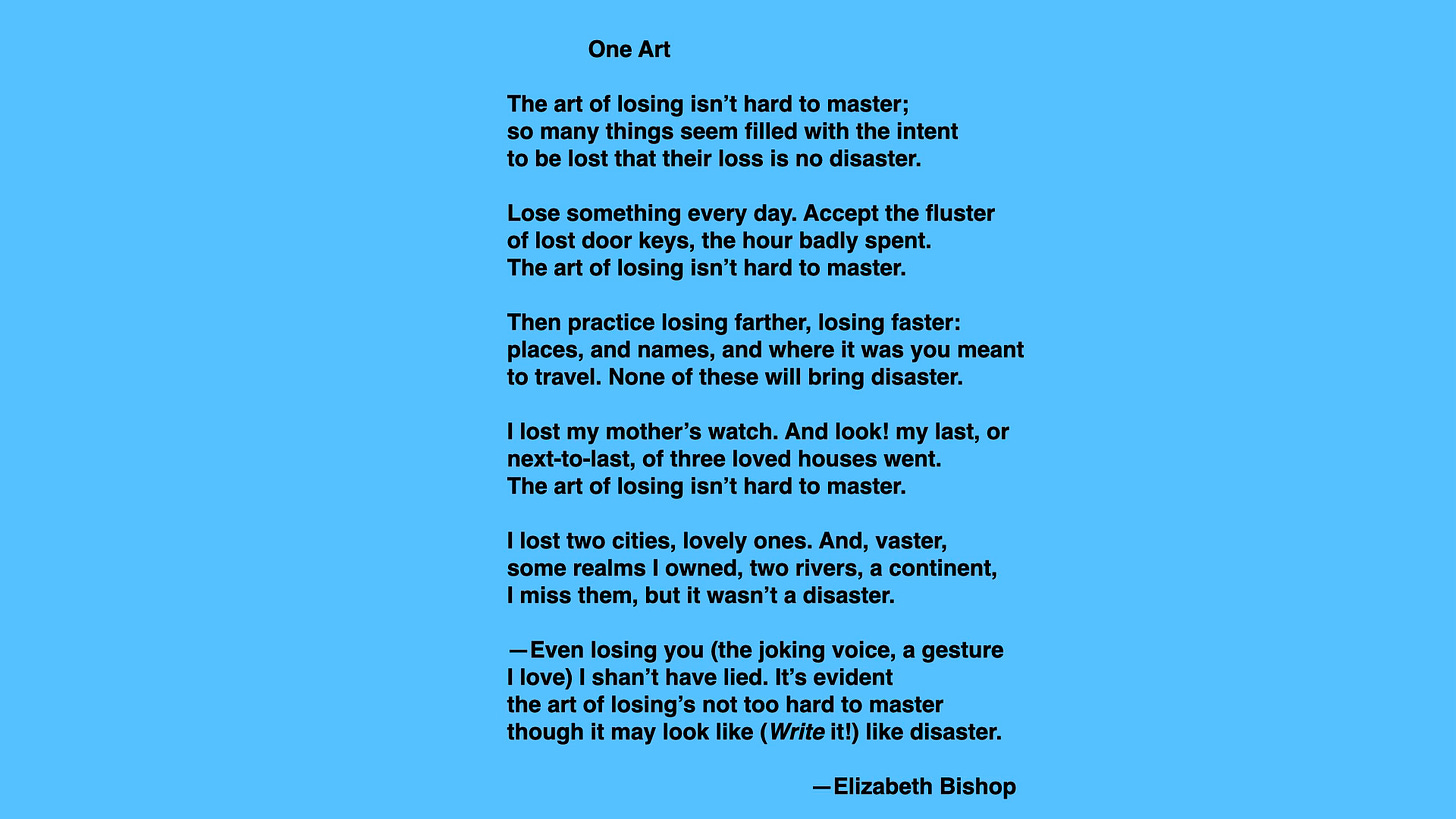

Here’s Elizabeth Bishop to close.

Mary Tabor writes

[i] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Portable Nietzsche, The Gay Science, “The Madman,” ed. and trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: The Penguin Group, paperbound edition, 1976).

[ii] Peter Faulkner, Modernism (London: Methuen & Co Ltd, 1977).

[iii] Randall Stevenson, Modernist Fiction: An Introduction (Hertfordshire, England: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1992).

[iv] Stephen Spender, The Struggle of the Modern (California: University of California Press, 1963)

[v] Gerhard Kurz, “Nietzsche, Freud, and Kafka,” trans. Neil Donahue, Reading Kafka, ed. Mark Anderson (New York: Schocken Books Inc., 1989).

[vi] Virginia Woolf, Collected Essays, Volume IV (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., 1967).

A compelling argument. Art can also be a way of shaping chaotic experiences, giving them order, and thereby gaining control over those memories.

I also wonder if sometimes art can just be a celebration of wonder or a form of play. Our own lives might end, but does that imply nothingness? All around us there are children playing, flowers blooming, bees doing their thing. I'm starting to question the nothingness premise. Even as a humanist, I think it's possible to reject the notion that there's no inherent meaning in the world.

Lovely, thought provoking essay. Of the three works you discuss, I’m most familiar with “To the Lighthouse.” I try to read it once a year, without much success. (October, already!) I read “The Trial” and “Ulysses” many years ago; willing to go back to the latter. I find Woolf’s interiority more compelling, and accessible. I think it’s brilliant that you’ve grouped these three books and writers together.

As to your invitation to join you as a guest in 2025: YES! This is a great honor. Thank you for your invitation. I’m working my way through the incredible posts here. Woolf can wait.😊