“Everybody is a book of blood; wherever we're opened, we're red.”

― Clive Barker, Books of Blood: Volumes One to Three

Origins

It started with a DNA test.

The human body contains approximately 30,000 genes composed of three billion pairs of DNA molecules. All of the diversity and richness of our species flows from slightly different combinations of the nucleotides we’ve named “A,” “C,” “G,” and “T.” While the vast majority of Homo sapiens have the same core genes—our DNA is 98.8% identical to chimpanzees—slight sequence changes account for huge variations in height, weight, appearance, intelligence, talents, and disease susceptibility. For some people, the bad luck of a single mutation changing one “letter” in their genetic “book” can result in a potentially fatal blood disorder like sickle cell anemia or hemophilia.

Tiny differences in DNA, spread across many chromosomes, can be used to pinpoint a person’s identity with near perfect accuracy. Notorious cold case murders like the Golden State Killer have been solved through DNA testing. DNA can also reveal other truths, like tracing the immigration history and ethnic origins of families.

In 2017, my wife and I decided to take commercial DNA tests through 23andMe for fun. As a vet and PhD student in cancer biology, I was interested in the health implications, and we were curious how much it could tell us about our distant ancestry. We were also getting married the following year, so we half-kiddingly told people we wanted to make sure we weren’t related (such things have happened before). I even joked with my family before sending off the kits:

“So now would be a good time to let us know if there’s any sketchy weird family secrets about ancestry or relatives lol”

Their answer: Nope, not that we know of.

***

When I got the ethnicity results back months later, some of them fit with what I knew from my parents—I had big chunks of heritage from Germany and the British Isles. However, the two largest region matches were Italy and Eastern Europe (Poland):

Those two regions came out of left field. My maternal grandfather was 100% German and my maternal grandmother was from the southeastern US, tracing her roots back to colonists in the 18th century (before major waves of immigration from Italy or Eastern Europe). My dad’s family was entirely from Britain and Ireland.

In terms of relative matches, there were thousands of people who shared tiny amounts of DNA with me, mostly 4th and 5th cousins. I recognized a few surnames from my mom’s side, but nobody close popped up.

When I shared these results with my family, they were just as confused. They said they didn’t know the complete story on their family trees, so maybe some hidden backstory explained it. They also questioned how accurate those consumer DNA tests were…

You Have A Match!

After the initial excitement and investigation, I forgot about those results and went about my life. Then, one day in 2018 when I was being treated for hyperthyroidism—a heritable disease that runs in my family—at the University of Alabama at Birmingham teaching hospital, some nice folks asked if I wanted to give a little extra blood during my regular lab-work draw to help a large genomics research project at the NIH called All of Us. Part of the sweetener was additional medical information about heart disease and cancer risks, and they would also provide an ethnicity estimate. I knew how difficult it could be to get patient samples from my own research, so I was happy to help.

As with everything in academia, the results took forever. I ultimately got the ethnicity results back years later, during the middle of the covid-19 pandemic. These results were a little more crude:

40% Northern and Central Europe (Ireland, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Scandinavia, and parts of eastern Europe)

33% Southern Europe and the Mediterranean (the Balkans, Italy, and Greece)

27% Eastern Europe (Poland, Ukraine, and Russia)

Ok, now I was paying attention. I could write-off those first weird results from 23andMe as noise or a bad algorithm. But this was a respected university lab that got very similar results from a blood test (instead of spitting into a tube).

I wanted—no, needed—answers.

Doing genealogy research online, I found that many DNA detectives recommended testing through Ancestry.com because their database is many times larger than 23andMe and it is easier to find relatives. I sent the test off in late 2022 and waited for the results to come back. While I stewed anxiously, I pursued any avenue that might give me clues.

I uploaded my raw DNA to GEDmatch, FamilyTree DNA, and other open-source sites that allow cross-comparison between platforms. Much to my shock, one of these popped up with a close male relative I had never heard of before:

A quick aside on how commercial DNA test matches work: The amount of genetic material shared between any two individuals is measured in units called centimorgans (cM). While you can’t always determine the precise nature of a relationship from that score alone (see the different suggestions above), the higher the cM, the closer the familial relationship, as you can see from this chart:

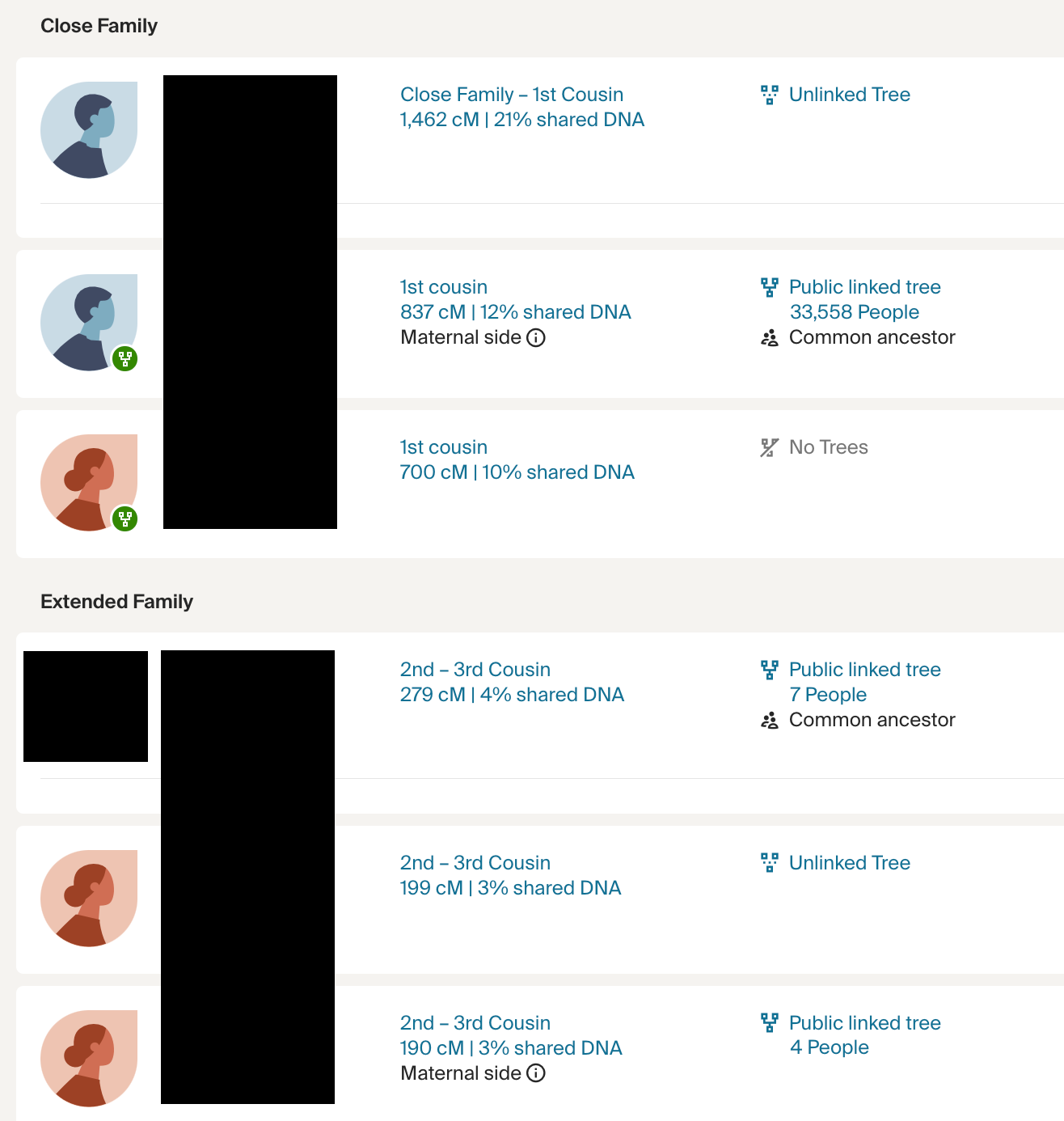

At 1,499 cM (roughly 21% shared DNA), they were outside the range for possibilities like a cousin or more distant relative. Different sites predicted relationships including uncle, grandfather, half-sibling, or nephew as the most likely possibilities. Whoever this person was, they were a very close relative that I never knew existed.

Triangulating further requires knowing a person’s age (for example, someone who is 25 years old couldn’t be my grandfather, and a nephew couldn’t be older than my brother), shared relative matches, whether they are on your paternal or mother’s side, and ideally some portion of a family tree.

There was little information to go on beyond a name, gender, and a Yahoo email address I feared was old and no longer active. I drafted an email anyway and sent it off.

Weeks passed.

Then months.

No response.

NPE

At this point, things weren’t adding up, and I had a few theories about what might be going on; unfortunately, many of the possibilities could be explosive for my family…

Was there an affair? A secret adoption? A sperm or egg donor? Switched at birth at the hospital? Some other weird explanation?

As luck would have it, my dad’s brother is a genealogy buff who posts about it all the time (his Ancestry.com results came back 83% British/Irish, FYI) and he had uploaded his results to GEDMatch, too.

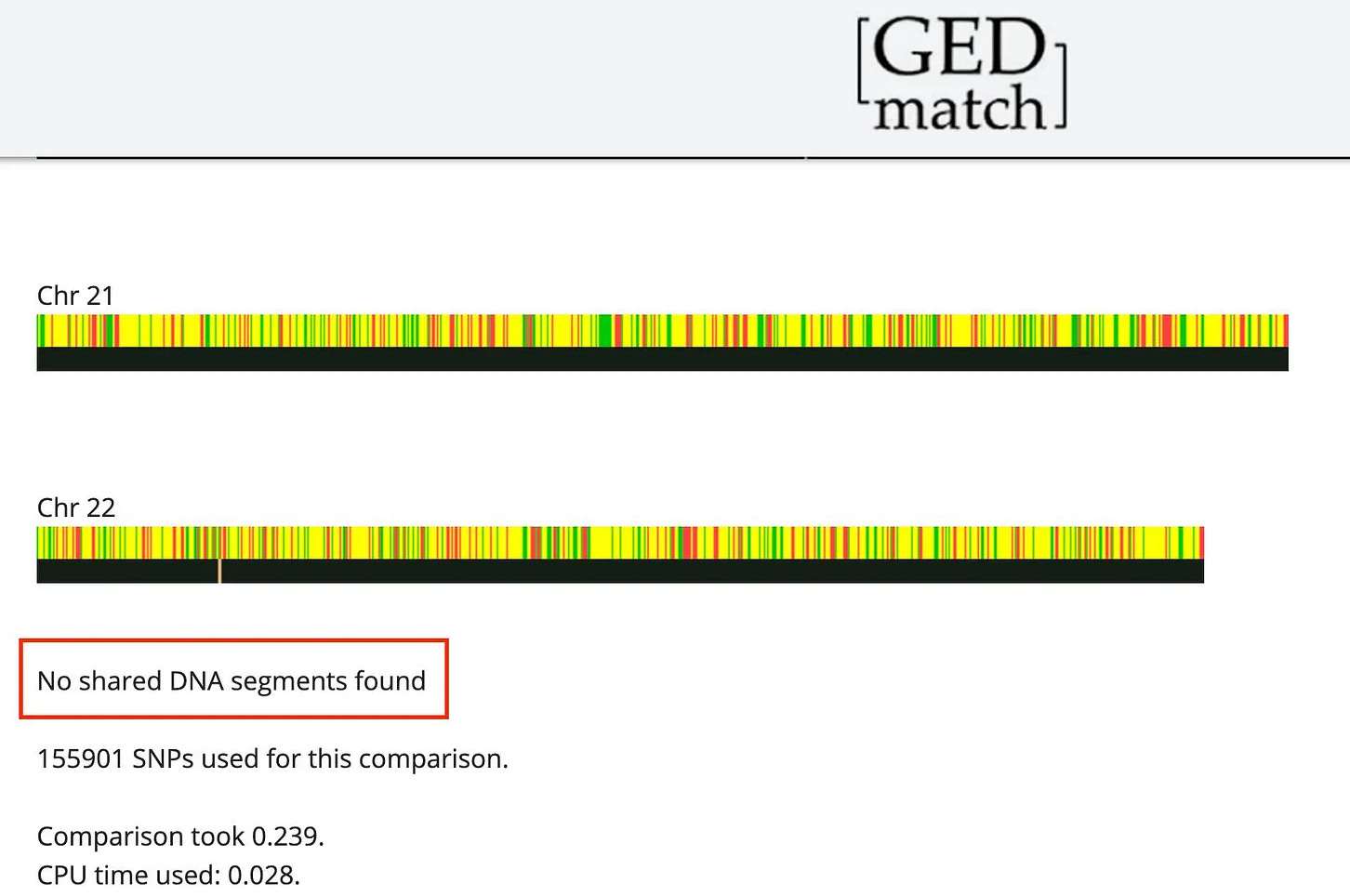

I selected both of our genomes and clicked the “One-to-One” comparison tool. The analysis came back in less than a second:

My uncle and I were not a match.

I felt a lump in my throat and a sense of vertigo.

This confirmed my worst suspicion: At the age of 38, I found out that the man who raised me was not my biological father.

***

The DNA test had revealed I was an NPE: a “Non-Paternity Event” or “Not Parent Expected.” NPE is the term used when ancestry records or genetic testing reveals one or both biological parents are different than who is on a person’s birth certificate.

These are the stories you read about online, but never think would happen to you. While concrete numbers on the prevalence of NPEs are hard to come by, some estimate that the rate may be 5% or higher. This means there are millions of people in the US alone who are NPEs, and since only a small minority of people take DNA tests, many are likely walking around completely unaware.

This revelation turned my world upside down.

It is hard to put the feelings into words unless you have experienced it yourself. The closest way I can describe it is similar to the dysphoria my transgender friends talk about, a visceral sense that you are in the wrong body, that your physical features are somehow off.

When I looked in the mirror, I wondered where half of my face came from.

Did my biological father share the same prominent nose, which I had been teased about all my life?

Is that where my thick curly brown hair—that is thankfully not thinning yet—came from?

Was he also short?

Did he have a similar voice?

Sense of humor?

How alike were our personalities?

What did they do for a living?

There were more questions than ever, but I was no closer to an answer.

Breakthrough

My initial shock was followed by determination to get to the bottom of this situation.

By now I had gotten the Ancestry.com results back. The heritage predictions were almost identical to 23andMe and UAB/NIH, so I was three-for-three. Sorry skeptics, the DNA results weren’t a fluke.

Unlike 23andMe, Ancestry was a treasure-trove of matches and the unknown relative above was my closest. Two known first cousins on my mom’s side were on there. And there were a handful of second and third cousins; people that closely related can usually be traced to find great-grandparents, if not grandparents as well.

I set to work, digging through historical records and constructing family trees with the help of “search angels,” genealogy sleuths that help connect adoptees and other NPEs with long lost family. I messaged a handful of close matches across the platform. Most never replied, which is sadly all too common. I was frustrated to continually find promising leads only to hit dead ends when messages were ignored or the paper trail went cold.

One day in April 2023, my highest match in the extended family range wrote me back a nice message that they were interested in helping. This person had previously met up with some distant relatives and passed on the name and email of a 91 year old gentleman who was the family genealogy buff and record keeper. They also passed on a detailed family tree that lined up with one I was constructing and filled in some gaps. A light bulb went off: that family genealogist was closely related to several of my candidates for biological father.

I sent off an email with low expectations, given how many other people ignored my messages.

The Truth

I got a reply on May 24th, 2023.

We had a few emails back and forth where I shared my background and the results of my ancestry sleuthing. I discussed that I knew my parents had struggled to have kids and had consulted some fertility clinics in the area. I was pretty sure I had been born through IVF.

I proposed my theory: I was born not only via IVF, but through the use of either a sperm donor or “sperm mixing” (a dubious practice from the 1970s to early 90s), and he was related to that person in some way. I provided the name of the hospital, fertility doctor, and my birthday.

“BINGO!!!!!!” was the first line of his next email.

His son was a graduate student in that exact fertility clinic working for the same doctor and was asked to be a donor during his time there, which lined up with my conception. He had since gone on to become a physician himself. I was talking to my biological grandfather.

He was clearly very excited to meet me and proceeded to share a lot of family history. His parents were both 100% Polish, with his father born in Poland and emigrating to the US as a young child in the early 20th century, while his mother was a 2nd generation Pole born in Western New York to immigrant parents. His wife is 100% Italian, with both her parents born in the same small village in Sicily.

Incidentally, 23andMe’s predicted timeline of ancestors and location were both close in years and within a handful of miles to where I now know those biological forebears to be from.

He shared photos of his son along with stories and personality quirks. One of the images of him as a young child is eerily similar to one of me hanging in my parents’ house. He even mailed me some records and passed on an email address of my donor, who I contacted shortly thereafter.

My excitement was short-lived. I never got a direct response back from him. A few weeks later, his father sent me a follow-up email that after considering sending me a letter, he changed his mind and did not want any contact. I was hurt, but told them I would respect his privacy.

***

That fall, after months of working through these events and complicated emotions in therapy, I decided to confront my parents. I was so nervous. Part of me wondered if this news would be a complete shock to them, and I would be destroying the world of two people in their 70s.

Another possibility was one parent knew, but kept it secret from the other (as well as me), which would result in a catastrophic rupture of trust between them.

As I got involved in the donor conceived community, I had even heard horror stories about parents who had a heart attack when the truth came out.

I called them on Wednesday night in October when I was out of town working a university job. Popping in my AirPods, I paced throughout the conversation. We made small talk for a while, almost half hour, before I found an opening to broach the subject.

Hey, do you remember me telling you about those DNA tests a while back?

I started gently, asking open-ended questions about their fertility journey that I had asked in the past year to try and provide them a natural opportunity to tell their side of the story. I brought up the weird ethnicity results, the unknown close relative, even the non-match with my uncle. At each turn, they feigned surprise and replied with a denial or a deflection.

Eventually, I told them the full story, including that I had received confirmation from the donor’s family. The walls dropped and they started telling the truth.

***

We kept the conversation going over several weeks. I explained to them how shocking this discovery was and how the lies of both omission and commission had been so damaging. They apologized and told me they never meant to hurt me and that they were told to keep the whole situation secret.

I believe them. As shocking as it may seem in 2024, for decades doctors in the fertility industry counseled patients to cover this up and never tell anyone, long after this was considered bad practice in the adoption community. Some of this may have been to protect the anonymity of donors. Some of it was probably linked to concerns about legal rights and inheritance—laws discriminating against children born out of wedlock in various ways were still on the books in the US until the Supreme Court struck them down in the 1970s.

However, I believe the biggest driver at that time was infertility trauma and shame. Many couples who can’t conceive naturally feel a sense of failure and guilt that they were not able to do what so many people are able to do, often without even trying. This was compounded by how new the technology was—the first baby born via IVF worldwide was only in 1978, a few years before I was conceived.

I’m sure nobody at that time foresaw a world where low-cost, direct-to-consumer genetic testing would be available, but that is the case today. The truth will eventually come out; the main question is whether you want it to be a controlled release, coming from a place of love, or an accidental, traumatic discovery from a third party. I’m reminded of this line from the HBO dramatization Chernobyl:

I have empathy for my parents’ pain and struggles, I really do. That doesn’t change mine. Some wounds can only be healed by time, and honest discussion is the first step.

What would I tell any other parents in this situation? The best time to tell your kids was yesterday, the second best time is today.

Aftermath

Over the past six months, everything has changed, and nothing has changed.

The unknown relative I matched with earlier returned my email late in the summer of 2023. It turned out he is my half-brother. They are one year older than me and were born through IVF with a sperm donor at the same clinic my parents used. Their parents had always been open with them about the situation and they had joined the DNA testing sites to try and find any other half-siblings. What’s more, they were raised with a brother who is a year younger than me and was also donor-conceived in the same facility. His brother did not take their own DNA test, but their face is nearly a photocopy of the donor’s. So I have at least two half-brothers, and in all likelihood, there are a few more out there, since my donor was active for years and most people never take DNA tests.

After a few emails back and forth, we agreed to meet up in person when it coincided with a work trip of mine. We met for Mexican food at Taqueria Dos Hermanos (I kid you not, though they claim they didn’t even think about the translation when picking a venue). Over several hours, we caught up on more than three decades of missed time. It was amazing to see the ways in which we were similar (aspects of appearance, hobbies, some personality traits) and different (jobs, families, interests).

We’ve had a few texts back and forth since, but no other get-togethers. We live far apart and have different lives. While I’m open to building a relationship, that depends on their interest, and it will innately be harder as adults with our own families. Part of me grieves not having the opportunity to know them when I was younger when it may have been more practical to bond. In fact, they live just down the road from a place I used to work years ago. Life is full of odd coincidences.

***

It will take a while for me to completely process the implications of being donor conceived.

For most of my life I’ve felt like an outsider, the black sheep of my family. They obviously love and care for me, but they often seemed like they couldn’t relate to me. My politics and interests are 180 different from them, and as it turns out, actually pretty similar to my donor. I was often teased as being the “Lisa Simpson” of the family, for being a “smarty pants” and sometimes accused of thinking I was better than them.

On top of that, it always bothered me that I didn’t resemble my dad. In college and graduate school, many people doubted I was Irish and insisted I had to be Jewish, Italian, or another ethnicity. Turns out they were on to something.

I didn’t have the vocabulary to even articulate that concern and it felt like a forbidden taboo. This cognitive dissonance was compounded by everyone in my family, including those who knew the full story, saying things like:

“Why are you like this? Your father isn’t like this!”

“You look/act so much like your cousin”

Even at the beginning of the call when I first confronted them, during the small talk they made an offhand comment “You were tall as a child like your dad.”

Now, I find myself caught in the liminal space between two fathers: one who raised me but often didn’t “get” me, and one who contributed the genes that make up half of my body, yet has no interest in even returning an email to me.

People in my family repeated the phrase “Blood is thicker than water” a lot growing up. Those words have taken on new layers of nuance and complexity in light of these revelations. If this journey has shown me anything, it is the value of chosen family, and that blood relation is not everything.

On the other hand, it’s also not nothing. For those who are all-in on the importance of family environment over genes in the “nature vs nurture” debate, it’s hard to argue the former isn’t important when my life trajectory has in many ways mirrored that of a stranger I’ve never met. I find it ironic that virtually anyone would consider a child whose biological father left or died before they were born to have experienced trauma, but so many donor-conceived people are told those feelings aren’t valid, just get over it already, it shouldn’t matter because “your father is the one who raised you.”

***

Some people ask me:

Are you glad you know the truth? If you could go back in time, would you choose not to take this test which has radically upended your life?

To me, those are non-sensical questions. This is the truth flowing in my veins and it is true whether I was aware of it or not. Half of my physical and personality attributes are carbon copies of a person thousands of miles away I only “know” through pictures and secondhand anecdotes. The secret of my origins for almost four decades shaped who I am as a person, even if I was not in on that knowledge.

Along with all of the discomfort, I have found some measure of relief in the explanatory power those tests had. Many confusing things in my life that never made sense clicked into place afterwards. Where I used to feel guilt at being so different, I now understand much of it was out of my control. You could call it “cellular kismet.” I wouldn’t take that back.

I’ve spent my life trying to explore the world and better understand myself through tireless study. There is a video of me as a two-year-old stomping around demanding “I. NEED. DETAILS!!!” It turns out that affinity for biology and a curiosity for the unknown runs in the family. I am a scientist and veterinarian who received advanced training in genetics and hematology. In retrospect, me doing this detective work into my own roots feels almost inevitable. You could say it is, after all, in my blood.

If you or anyone you know is going through donor conception or just discovered you are donor conceived, I would encourage you to visit this organization for helpful resources:

https://www.wearedonorconceived.com/

Eric Fish writes All Science Great & Small

![Every lie we tell incurs a debt to the truth. Sooner or later that debt is paid." - Valery Legasov (quoted in the Chernobyl series) - [1260x662] : r/QuotesPorn Every lie we tell incurs a debt to the truth. Sooner or later that debt is paid." - Valery Legasov (quoted in the Chernobyl series) - [1260x662] : r/QuotesPorn](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!kpGe!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6747fa93-3f37-4192-905a-4e9a370083da_1260x662.jpeg)

Lovely, Eric -- and great questions about the ethics of these situations. As you say, it does seem like full transparency is the best policy with kids. Knowing our roots is important. It's why I turned to genealogy after leaving academia, searching for a deeper foundation for rebuilding my identity. I hope those conversations continue to unfold with openness and compassion in your family.

I also like your phrase "cellular kismet." It's so strange that many of us experience that even within our own families. During my own genealogical research, I discovered that DNA isn't split equally among one's children. For instance, my ex-wife's Italian genes might be overrepresented in one of our kids, whereas another child might have a disproportionate share of my Czech genes. There are probably limits to how deterministic those gene sets are -- how "baked-in" certain traits might be. But even as the biological child of my parents, I often experienced a kind of dysphoria, thinking I was breaking from family tradition by going to college. When I discovered that one of my great grandfathers had been a professor, I had an awakening similar to yours -- a homecoming to the self, you might say.

We're all hungry for answers to the mystery of self. I think this is why almost everyone who does an ancestry DNA analysis ends up saying "That explains a lot."

Thanks again for sharing your story!

Thank you for sharing your story. I, too, am an NPE and the memoir I’ve written is all about this discovery, its aftermath, and the psychological underpinnings that complicated it all. I was struck by a word you used describing the moment if your discovery—vertigo. Dani Shapiro had that same experience. As do I…though my unmooring was lasting. It’s so hard to understand why something that “changes everything but changes nothing” can feel so destabilizing. I so relate to your experiences and am glad you kept pursuing in order to know the truth.