I really recommend to everyone living outside of your home country for a bit — not just for travel but actually for some time. The experience isn’t just about whatever your country you happen to be in, it’s also a very complicated, fraught dialogue with where you come from.

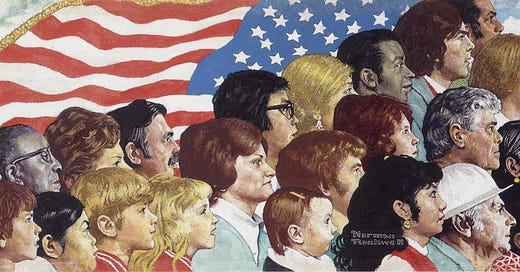

In my case, the way this internal dialogue has played out is becoming very aware of the ‘positive propaganda’ of my upbringing. I came across this term a few years ago — I think I heard it from a Russian — and I’ve really found it to be very useful. The idea is that propaganda is not just the two minute hate, the railing against enemies, or the buttering up of the Dear Leader. Propaganda is also the air you breathe, it’s some of the most cherished memories you have. It’s the way that your experience is landscaped for you, very often — maybe especially — from early childhood and done so with the intention of building a sense of loyalty to where you’re from. There’s nothing necessarily wrong with ‘positive propaganda’ — it’s very difficult to distinguish between it and ‘community’ — but what happens as you spend more time in a place that’s not your home is that much of the positive propaganda starts to lose its spell, or at least you see the outlines of it in a way that is very hard to do when you’re steeped in the culture.

Here’s what I have noticed is the positive propaganda of the US:

America is the greatest country in the world. Everybody sort of believes this — it’s a cornerstone of human vanity — but Americans really seriously believe it about themselves. In America, it takes a curious form — that sort of as Mohammad is the last prophet, that America is the last country i.e. that the future rests with America. That seemed to be unequivocally true in the relationship between Europe and the U.S. — even just in the terminology of ‘old world’ and ‘new world’ — but it’s clearly no longer the case. America has been around for a while, it’s clearly established what it is, Gertrude Stein’s quip that “America is the oldest country in the world” (i.e. the country that went through modernity first) is becoming obviously truer by, like, the day, and it’s already becoming clear that there are other societies that more clearly stand for what we might think of as the future — China, Singapore, Dubai, etc. That’s not to say that those other societies will necessarily win out in the war of ideas — Fascism and Marxist-Leninism once seemed like ‘the future’ — but to the rest of the world the U.S.’ smug conviction that it’s the ‘greatest country in the world,’ the behemoth, already looks, if not exactly wrong, then outdated.

America has a higher living standard than anywhere else. This was an article of faith the entire time I was growing up. I believed that not only was America the ‘richest country in the world’ but that its wealth rested on an unassailably solid middle class — and that no country in the world had anything like what America had or was likely to have anytime soon. And that turns out to simply not be true. Economic inequality means not only high rates of poverty in the midst of ‘the richest country in the world’ but a vast prevaricate of people who give the appearance of being middle class but, unless they are in a handful of super-solid sectors, are really just scraping by. In living standard, the United States is somewhere around 25th in the world, on par with Poland or Slovenia. We can argue for a long time about why that’s the case. The U.S. really does generate the most wealth in the world — the corporate sector and tech are more developed than anywhere else — but it just doesn’t necessarily translate to better lives for Americans. Capitalism certainly comes in for discussion here, as does widening inequality. The failure of the U.S. to provide effective health care is certainly noteworthy. Left and right alike would question the expenditure of so much money on defense — and on a security blanket for far-flung allies — and a new discourse has emerged, notably in the catchphrase ‘abundance’ asking ‘why nothing works’ and pinning the blame on an overabundance of red tape within government.

The rest of the world is mired in the dark. It always surprises me talking to Americans — even older Americans, people who should be worldly — the extent to which they assume that the rest of the world is trapped in intractable cycles of poverty, beset by civil wars and autocracy. My sense is that this is the famous American provincialism — Americans simply don’t travel that much, and don’t travel beyond a few choice destinations — and so they let media create a picture of the rest of the world for them, and media, through its inner logic, depicts a sea of problems: crime, terrorism, environmental catastrophe, you name it. Americans tend to have retained Cold War propaganda, to feel that they are the citadel of the free world — that “this is the light and all around its margins is the gulf” — or that, as John Updike put it, “America is absolutely it.” It just hasn’t really occurred to a lot of Americans that the rest of the world is doing alright — different countries evolving in their own ways, and that it’s not all backwards peoples dodging terrorist attacks and waiting for the release of the next Arnold Schwarzenegger film.

America has a unique destiny. I’m not sure that any other country has quite the same messianic sense of its own destiny that the U.S. does. What that’s based on is being new, and throughout American history astonishingly self-serving narratives (manifest destiny, American triumphalism, etc) have been put forward with straight faces. Now that the wind has clearly gone out of the U.S.’ sails, and we’re no longer in the American Century, a real crisis of faith has emerged among Americans: if the U.S.’ mission isn’t to be “the world’s last best hope” or “the leader of the free world,” then it feels necessary to reshuffle the decks completely, to create new narratives about the “original sin” of the U.S. on race, about the U.S. as a victim of its own hubris. It seems very difficult for everyone to simply step outside that narrative, to see the U.S. as a country like any other — with a uniquely well-protected geographical configuration (this was the geography lesson that Zelensky was trying to give Trump in the White House before he was so rudely interrupted) — but just as subject to the volatility of history as anyone else.

Democracy is a shield against everything. I remember being very struck by a documentary I saw about Al Jazeera in the 2000s when an Al Jazeera reporter said something to the effect of “I have total faith in the U.S. Constitution and in U.S. government.” It was surprising to hear somebody outside the U.S. say that, but most Americans probably believe something similar. What everybody except high school smart alecks has struggled to grasp is how far the American political system really has wandered from true democracy — very little actual power is at the local level, and power has consolidated in pockets of big business, an entrenched bureaucracy, and party machines locked into competition with each other and with very little accountability to the public. What Trump is showing us, more than anything else, is that government institutions are vulnerable — just as all government institutions are vulnerable in any country the world over. Other countries have coups, and strongmen, and tumult — why not the U.S.? The belief in the U.S. is that the Constitution is unique, something like holy writ, the very most perfect jenga-set of checks and balances. And, in spite of my occasional ribbing, the Constitution, I have to concede, is definitely ok, a well-designed structure of government that took into account a surprising number of difficulties stretching far into the future. But we shouldn’t kid ourselves that the Constitution is perfect. The presidency has an inherently unstable relationship to the other branches, and it’s sort of inevitable — as per any fall of Rome book you are likely to pick up — that Congress would gradually weaken over time while the presidency strengthened. Meanwhile, the Constitution had very little prescience when it came to political parties, or the role of money in politics, or the civil service — and the atrophy with time is to a bloated administrative regime of lobbyists, or bureaucrats, or think tankers, or one isn’t even sure what, but none of whom seem to be directly accountable to the majority rule of the people.

America is fundamentally an innocent but also a force for good in the world. This is one of my pet peeves — and a direct result, I think, of Americans’ reluctance to travel. Americans really do kind of think that America ends at the oceans, and have very little sense of how deeply enmeshed American power is with the rest of the world. It’s a complicated story — I’m far from able to understand it fully — but American power extends to a security blanket stretched across Europe and the Pacific Rim; to the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency; to the ubiquity of English; to the cultural capital of Hollywood and the music industry. I remember a Russian once saying to me, “We all have two nationalities: our own and American.” America is an immense cultural totem for just about everybody — symbolizing capitalism, a kind of silly, stumbly optimism, and a curious buoyancy that’s connected to democracy. Americans, I think, have very little sense of how just about everything we do has two lives — the action itself and then the way it ripples out to the rest of the world. Americans tend to start and end their analysis of themselves with a kind of eternal innocence, but America hasn’t been innocent for some time. It’s time to grow up and to at least be able to see ourselves as others do.

Sam Kahn writes

and edits .

Two things I've noticed while living abroad: 1) being an intellectual or artist is not seen as childish in quite the way that Americans make it seem; and 2) knowledge of history is equated with sophistication and maturity.

In those ways I think I belong more in international spaces. I've never had to make a living abroad (other than for a brief stint as a teacher in Uruguay) or raise a family there or contend with the full scale of costs and sacrifices that factor into quality of life. But my default is communal, not solitary, when I start a conversation with someone I expect it will last more than a few beats, and I'm always eager to look beneath the hood of a place -- all of which are more or less welcomed in most of the countries I've visited (Canada maybe less so).

The thing to add to your list is that America is perhaps the country with the vastest amounts of wilderness. Perhaps South America still has more, but it's not developed to the point of being able to easily backpack and "disappear" into the wild. Perhaps I'm wrong about that?

I was born in 1942 in the US and therefore my particularly formative years were the 1950s. This resonates with me completely - I have lived in London since 1968 and still swing from seeing the US as "us" or "them" but it is more and more "them".