June 16th was Bloomsday1! Hurrah!

Goodness in Leopold Bloom and how to read Ulysses

In this brief essay, I focus on James Joyce’s Ulysses—even in the face of the seeming impossibility of doing that with this tome of a novel: A good story, a compelling story, full of humor and life that captures the heart and imagination.

I’m gonna tell you how to conquer it and why you’ll be glad you did.

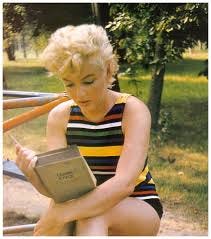

Ulysses has an imposing reputation and a difficult narrative style. Those of us, like me who read it in undergraduate and graduate school, read it along with a book that was longer than the novel—Ulysses Annotated. That book is the key to the allusions that pepper every page. I’ve done it that way twice.

But as someone who reads deeply—and someone who reads to save my life—I suggest another way to attack this biggy.

The novel should be read for the powerful story that it is.

Read it through and skim anything you don’t get. Here’s why: When you get caught up in trying to understand every allusion—and Joyce did something incredibly complex on that score—you lose the story, the life of the book.

I argue that this book has lasted not because it’s so complicated but because it really does live and breathe.

The writer Anthony Burgess in a terrific little book in size ReJoyce, but large in ease of reading, says about Ulysses: “Let it join the beside library along with Shakespeare and the Bible.”

Joyce’s Ulysses is a big book. Joyce is imposingly erudite, but the novel is no solemn text. Joyce was a great humorist and humanist.

His style changed the modern world of literature. He recreates what thought might be like if written down. We get jolting shifts in style and a disjointed narrative that makes sense.

I’ve come to understand what the critic Hugh Kenner meant when he called Joyce “The Arranger.” He plays games with us and it’s well worth playing along.

By the second half of the book, where the chapters get longer and longer, it’s almost as if he’s recreating what someone is saying in real time. The book has the quality of great cinema—it engulfs you in its world.

I focus my camera here on the remarkable main character Leopold Bloom, who journeys through that one day June 16th on a parallel latitude in Dublin with the young man, Stephen Dedalus, until their paths inevitably cross.

Joyce has created in Leopold Bloom a character who embodies goodness—not the spiritual goodness of a saint, but that of a man confronted with his own sensuality, his own failures and the world as it is, not as one might wish it to be.

Leopold Bloom is the most human, flawed, forgivable and forgiving character ever to appear in literature.

Okay, yep, I’m over the top on this one, but stick with me.

You can hear me on XM Sirius radio discussing the book along with an audible.com short excerpt read by Irish actor Jim Norton here after a 20-second Father’s Day intro:

Bloom becomes our hero, our fallible Ulysses, who, like us, is confronted with his own failures. Bloom, an outsider, a Jew, shunned by others, the object of derision and anti-Semitism is an ordinary man, cuckolded by his wife, the woman he loves.

The power of the story comes from his simple nobility and unfailing inability to pass judgment. We see him unfold before us moving inevitably and surprisingly toward the high-browed intellectual, self-important Stephen Dedalus, a sad much younger man in need of the simple wisdom and humanity of Bloom.

More anti-hero than hero, Bloom gives us bunches about his own bodily functions and plenty of sensuality. He’s even got a rather perverse obsession with women’s bloomers.

The pun on his name and his obsession is comically intended as we see in Molly’s soliloquy that closes the novel: Oft-quoted and likely more often read than the novel itself.

It’s Bloom who will capture your heart, bloomers and all.

Here’s one example from Chapter 18, the last chapter “Penelope”: In the midst of Molly’s soliloquy that begins with “Yes” and ends with that oft quoted “yes I said yes I will Yes” and with no punctuation in the intervening 1,610 lines

Molly says,

… and the new woman bloomers God send him sense and me more money I suppose theyre called after him I never thought that would be my name …

Hardly the picture of the Homeric hero.

And yet, I’m left by novel’s end with a pervasive sense of Bloom’s nobility, based on his actions, his opposition to violence, his sense of his own guilt and responsibility.

He tell us, “It is hard to lay down any hard and fast rules as to right and wrong ...”.

This unwillingness to pass judgment is the source of Bloom’s nobility, evidence of Joyce’s embrace of humanity with all its flaws, and one of the reasons this novel—with all its difficulties and challenges to analytical thought—touches the heart.

Bloom’s deeds, though hardly broad and sweeping, define him, as actions define each of us. The seed of Bloom’s actions lies in his sympathy for others.

Some examples that make me love him:

In Chapter 6, “Hades,” where Bloom crosses paths with Stephen’s father Simon, a character named Martin Cunningham appears. Cunningham also appears in the short story “Grace,” in Dubliners, and there too, he’s a man of mixed qualities, though his intentions seem good. Cunningham interrupts Bloom: “Martin Cunningham thwarted his speech rudely.” Yet Bloom recognizes goodness in Cunningham: “Sympathetic human man he is. Intelligent. Like Shakespeare’s face. Always a good word to say.”

It’s Bloom who remembers Mrs. Sinico, “Last time I was here was Mrs Sinico’s funeral”. Mrs Sinico also appears in the short story “A Painful Case,” in Dubliners and is portrayed there sympathetically, lost to love and ultimately to drink.

It’s Bloom whose “heavy pitying gaze absorbed her [Mrs Breen’s] news” in Chapter 8 “Lestrygonians” of Mina Purefoy’s “very stiff birth” and it’s Bloom who subsequently goes to visit Mina.

It’s Bloom who helps the blind man “tapping the curbstone with his slender cane,” careful not to condescend to him.

And it’s Bloom who “put his name down for five shillings” to help the widow Dignam. That mission of mercy lands him in the midst of the vicious attack by the citizen and the derision of others in Barney Kiernan’s pub, for he’s come “about this insurance of poor Dignam’s” who has died and left his wife penniless.

By the measure of others, Bloom, the butt of much derision, nonetheless fares well: Davy Berne says, “Decent quiet man he is ... He’s a safe man, I’d say.” And of course that oft quoted line, “There’s a touch of the artist about old Bloom.”

That “touch of the artist” is Joyce’s recognition of the artist’s sensitive nature, the artist’s inability to avoid seeing, to avoid hearing, to avoid the bombardment that is life in Dublin, Ireland.

In perhaps one of the the most powerful chapters of the book, “Cyclops”, Bloom expresses his opposition to capital punishment. “So they started talking about capital punishment and of course Bloom comes out with the why and wherefore...”.

What follows is a humorous discussion of what happens to the “poor bugger’s tool that’s being hanged”.

Bloom is the one who thought about the issues involved in the killing of the guilty.

Bloom’s opposition to violence doesn’t arise from a submissive nature. I say that because arguably Bloom behaves in a subservient manner in the novel. His opposition arises from conviction.

We get his strong verbal attack against the citizen: “Ireland, says Bloom. I was born here. Ireland ... . And I belong to a race too, says Bloom that is hated and persecuted ... I’m talking about injustice, says Bloom.”

Bloom understands, confronts, and deflates the arrogance and pomposity of both prejudice and nationalism that lead to violence in word and deed.

And he preaches all caps LOVE: “Love, says Bloom. I mean the opposite of hatred”.

When the citizen, or Polyphemous, blinded by sun, not by violence, hurls a biscuit box at Bloom, it’s to no avail. And we’re on Bloom’s side big time.

All this occurs amidst much jocularity and a striking parody of pompous language.

The serious point cannot be missed. Bloom makes clear in his retelling of the event to Stephen Dedalus that his views arise from his conviction: “I resent violence and intolerance in any shape or form”.

This is a gentle soul.

No wonder then that Bloom shall be the one to lead another, Stephen Dedalus, with a slender stick, the ashplant, to safety late in the novel. And we have the gentleness Bloom offers to Stephen when he rescues him in Nighttown: “Come home. You’ll get into trouble.” . . . “Face reminds me of his poor mother”.

No question he’s helped in his personal journey by meeting Stephen, a personal journey, layered with his relationship with his wife Molly and the loss of his son Rudy.

Honesty characterizes this imperfect man: It’s Bloom who makes us aware of his role in Molly’s betrayal. We learn from him that he’s not slept with Molly for eleven years since their son Rudy died only eleven days after his birth: “Could never like it again after Rudy”.

Bloom’s love of Molly is clear throughout. Even with his awareness of her tryst with Boylan, the man who’s her lover, he thinks of her wit and her beauty, as when he purchases the orange flower water for her: “Brings out the darkness of her eyes”.

In the “Circe” chapter that Molly haunts, Bloom says, “Last of my race. ... Well, my fault perhaps. No son. Rudy. Too late now. Or if not? If not? If still?” and our narrator comments, “He bore no hate”.

Cuckolded by Molly with Blazes Boylan, his love of Molly persists as does an awareness of his own responsibility.

Chapter 13, “Nausicaa” ends with nine cuckoos.

Meanwhile, Bloom has ejaculated to the sight of Gerty MacDowell, a young woman on the beach. He writes in the sand with a stick. “Mr Bloom with his stick gently vexed the thick sand at his foot. Write a message for her. Might remain. What?” and then “I” and then “AM. A.” — First letter of the alphabet and Alpha, sign of the fish, traditional symbol of Christ.

But you don’t need these notes to get what Joyce is doing.

The ”I AM” echoes Stephen early in the novel: “And the blame? As I am. As I am.” A reference to his guilt, his search and we hear the echo of Jesus in The New Testament, John, 8:58: “Before Abraham was, I am.”

Bloom’s surrealistic trial in Nighttown confirms for me his sense of guilt. “A fife and drum band is heard in the distance playing Kol Nidre”. Kol Nidre, the solemn prayer that opens the service on the eve of Yom Kippur, the Jewish day of atonement.

Throughout the story, Joyce gives us a man examining his life.

In that search, in his kindness to others, in his commitment to tolerance and forgiveness, we find goodness and nobility.

In Joyce’s use of stream of consciousness, the jolting shifts in style, the disjointed narrative, we find the chaos of existence and moral ambiguity. We find this in the way he tells the story, the technique that can seem off-putting.

But keep reading. Attack the novel as a story. Read it straight through, skip as you need to.

I’m betting you’ll marvel at Joyce’s embrace of humanity that emerges out of it all.

The writer John Berger in his essay “The First and Last Recipe: Ulysses” said “Ulysses is like an ocean. You don’t read it, you navigate it.”

I argue the best ways to do that, after reading it in academia with all the tomes and references written about it, is simply to read it. You’ll get one helluva story with simple, raw, erotic humanity.

Here’s John Berger, seven minutes that will be worth your time:

Mary Tabor writes

Here’s Colm Tóibín, one of my beloved authors, and other’s discussing the novel from The Morgan Library and Museum in Manhattan:

Bloomsday: A celebration that takes place every June 16th. This over 700-page novel takes place on a single day: Beginning at sunrise Thursday June 16, 1904 and ending in the pre-dawn hours of June 17. No matter how complex the telling, Joyce makes sure we know where we are and what time of day it is. I refer to this feat as a superb example of establishing “the now” – or the present action of the tale—another reason you will be able to navigate the story.

Late to this part, but want to say that I love how Substack allows for this kind of literary criticism. Like Carol, I feel more receptive to this book than I have been in the past because of your essay. This is perhaps moot now, but I think there was an interesting confluence between modernism and the rise of the public university that enabled writers like Joyce to produce "difficult" texts. This has been making the rounds, so I'm not the first to say it, but Cormac McCarthy would likely hit a brick wall if he were trying to catch an agent's eye today. I think even something like Silko's Ceremony or Almanac of the Dead would not appeal to the consolidated publishing market today. So, as much as I appreciate the value of wrestling with these literary classics, I'm also troubled by the fact that few of us can write like this today with any hope of being read. That's why I prefer Cather's approach to modernism (not that it's a competition :) -- I feel I can still grow as a writer and be received by readers today by emulating her aesthetic sensibility, which tends toward the accessible and the spare. As Cather said, the higher levels of art are all about simplification.

There was so much I considered as commentary while I was reading this, Mary -- until I got to the Berger, with which I was unfamiliar. Oh, my goodness, is it deep and moving (and how he reads it, with that voice), a period larger than a word on all you were saying. How can anyone who hasn't read Ulysses, or read it as you advise, not do it now?