Dear Friends,

For my pieces on Inner Life, I’d like to explore a few ‘classic,’ ‘famous’ essays - pieces that get referenced a lot, but which are easy enough to have missed. If nothing else, these are an opportunity to revisit the original essay - in this case Christopher Lasch’s ‘The Narcissist Society.’

Best wishes,

Sam Kahn

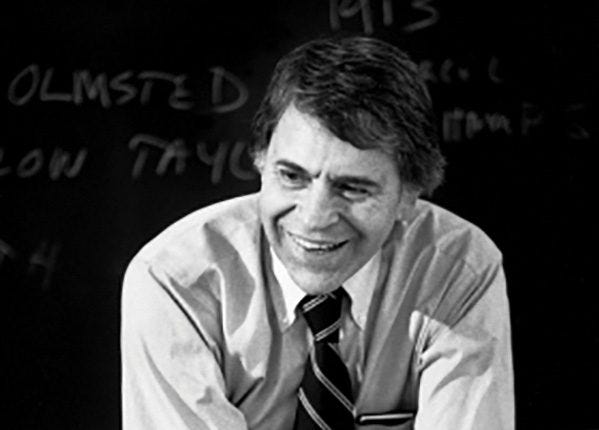

CHRISTOPHER LASCH’s ‘The Narcissist Society’

There are so many ways to feel stupid! There are the known unknowns — the books you’ve never gotten around to reading, the Ulysseses, the Magic Mountains — and then, worse than that, there are the unknown unknowns, when you come across a writer or thinker who really is wildly influential, who all these other people are in dialogue with, but whom, as it happens, you’ve never heard of.

Christopher Lasch was one of these figures for me, and then, in a row, I came across a series of references to him, articles reevaluating him, etc — and all with this weary tone, like sick of him we may be, but here’s one more discussion of Lasch. “Why do we keep coming back to Christopher Lasch?” queried Christian Lorentzen, for instance, in Jacobin.

It turns out that the idea most associated with Lasch — who, however, cut a wide swath, attacking various liberal orthodoxies, ripping into the deep heart of late-century American life — is ‘narcissism,’ the idea that narcissism isn’t just a clinical term but applies to the fundamental psychological structure of the culture-at-large.

Lasch expressed this idea in his 1979 book, The Culture of Narcissism, but it’s distilled in article form in his 1976 essay, ‘The Narcissist Society’ in The New York Review of Books — and accessible (pro tip here) via the wonderfully Inspector Gadget-y website removepaywall.com.

The essay, largely, is Lasch’s complaints about the 1970s — he is particularly livid about the New Age movement and about therapy. The point is that the end of the ‘60s marked a certain loss of faith in collective, outwardly-directed action. The move from there was all inward — into the self and into a particularly pious form of hedonism. This was sanctified, above all, in reigning therapeutic practices, of which Lasch writes:

Therapy is the modern successor to religion; but this does not imply that the “triumph of the therapeutic” constitutes a new religion in its own right. Therapy constitutes instead an antireligion, not always to be sure because it adheres to rational explanation or scientific methods of healing, as its practitioners would have us believe, but because modern society “has no future” and therefore gives no thought to anything beyond its immediate needs.

So, in other words, the ‘70s represented the onset of a new kind of nihilism. It wasn’t really a religious yearning — there was no millenarian sensibility, no turn either to the distant past or the eschatological future — so much as a vast sense of resignation, an acknowledgment of the triumph of behaviorism. And, within the framework of therapeutic discourse — actually emerging from the clinical literature — was a new ‘type,’ “superficially relaxed and tolerant,” well-sexed, smooth in their facility with clinical language, but fundamentally amoral, purposeless, and guided (thanks largely to the therapeutic regimes of the time) by an ethic of extreme self-centeredness.

The rise of the narcissists was, in Lasch’s view, not some dataset anomaly or a rectifiable matter of cause-and-effect. It was the deep truth of the era — its sociological and philosophical essence manifesting in an acute psychological form. “Every age develops its own peculiar forms of pathology, which express in exaggerated form its underlying character structure,” writes Lasch. “In Freud’s time, hysteria and obsessional neurosis carried to extremes the personality traits associated with the capitalist order at an earlier stage in its development — acquisitiveness, fanatical devotion to work, and a fierce repression of sexuality.” The therapeutic work of the half-century succeeding Freud had, to a surprising extent, cured the West of its repressions, but, within openness and sensuality, a different sort of demon had materialized —with no real identitarian roots and locked in the hall of mirrors of self-regard.

If Lasch’s fury against gestalt therapy, as well as health foods, can seem over-the-top, it’s hard to look at the last 45 years as a whole and not feel that Lasch was onto something. There’s, most obviously, the slide in political life — the certified narcissism of Trump but also the evident narcissism of a figure like Bill Clinton, the shift from a conception of the politician as humble public servant to a conception of the politician as the emotionally-redolent prism of the collective psyche. And then, almost as obviously, there’s the emphasis on atomization and individuality — ‘bowling alone’ as the descriptor of American life in the 1990s, just as the perfectly-named, era-defining ‘iPhone’ encapsulated the decades succeeding it. And then there’s the suspicion of any sort of public life — the widespread belief that collectivity is a sort of lie, that truth is to be found, if found anywhere, in radical selfhood. As Martin Gurri, Isaiah of the 2010s as Lasch was the Jeremiah of the 1970s, writes, “At the point where democratic governments are burdened with failure, democratic politics far removed from reality, and democratic programs drained of creative energy and thus of hope, the nihilist makes his appearance.” And Lasch, although he has a bit of a family values, conservative streak, isn’t so much advocating for rebuilding the white picket fence or getting back together with one’s estranged partner — for him, this set of developments is more seismic and inevitable. Discussing ‘the pervasive distrust of those in power,’ Lasch writes, “What looks to political scientists like voter apathy may represent a healthy skepticism about a political system in which lying has become endemic and routine.” In other words, the narcissist — or nihilist — emerges because fundamental social conditions are themselves nihilistic. “Narcissism appears realistically to represent the best way of coping with a dangerous world, and the prevailing social conditions therefore tend to bring out narcissistic traits that are present, in varying degrees, in everyone,” Lasch writes.

Lasch’s critique, by the way, closely mirrors that of Michel Houellebecq. Houellebecq, writing in 1998, lands on almost exactly the same chronology as Lasch and attaches the same importance to the New Age’s ersatz spirituality and cult of hedonism. In his novel Atomised, he writes, “A subtle but definitive change had occurred in Western society during 1974 or 1975, Western society had tipped towards something dark and dangerous. In the summer of 1976 it was already apparent that it would all end badly.” In Atomised, the narcissistic tendencies of the era are fulfilled in a minor character David di Meola, considered to be a well-adapted, more or less typical figure of his era, highly-sexed, semi-famous, but utterly without purpose, suspended, as Lasch would put it, between “inner emptiness” and “fantasies of omnipotence.” Di Meola ends up, sort of inevitably, becoming a producer of snuff films — his decadence, Houellebecq writes, “mirroring the progressive destruction of moral values in the sixties, seventies, eighties, and nineties as a logical, linear process.” In Lasch’s conception, those tendencies manifest, all these decades later, in Trump — that peculiar combination of self-regard and self-pity, the ability to make the public sphere entirely a reflection of his own brittle ego.

Lasch’s critique, like Houellebecq’s, is in many ways nihilistic. Atomised concludes with the — cheerful enough — extinction of the human race (which is understood, in the context of the novel, to be a necessary recourse). Lasch, meanwhile, contends that the West saved itself from the self-destructive ‘live for the moment’ myopia of the 1970s by reattaching itself to a vision of tech-driven futurism. Taking Lasch at his word of the state of things in the 1970s — all the disciplines bereft of solutions, “the natural sciences hastening to announce that science offers no cure for social problems” — the next decades essentially place all their faith in the microprocessor and in the ability of inexorably-advancing technology to solve the social problems that we couldn’t deal with on our own. Lasch spent much of the rest of his career assailing that belief in progress, but he must have recognized that that techno-faith, however naive, at least resolved the aporia of the 1970s and moved the West from the ‘anti-religion’ he discusses in ‘The Narcissist Society’ back to something closer to (inane) religion.

But, reading Lasch’s work of the 1970s, it becomes clear that what Lasch really was hoping for wasn’t some desperate clinging to the future but a reattachment to the past. “I see the past as a political and psychological treasury from which we draw the reserves that we need to cope with the future,” he writes in The Culture of Narcissism. “Our culture’s indifference to the past — which easily shades over into active hostility and rejection — furnishes the most telling proof of that culture’s bankruptcy.” And here I part company from Lasch slightly. I’m with him in his critique of the everybody-chant-OM-and-then-exit-through-the-gift-shop corruptions of spirituality — as egregious in our era as in his — but I sense that he may be underestimating the power of spirituality and of New Age movements. If nothing else, these movements tend to be rooted in the past — to believe that various cultures around the world, ancient, indigenous, etc, worked out techniques of self-actualization and of communal well-being that the materialist, ‘progress’-saturated West can stand to learn from. I’ve had my own run-arounds with the New Age, am fully cognizant of how permeable these movements are to charismatic narcissism, but at the heart of any sort of spirituality is a doctrine of self-work, a rigorous sense of personal responsibility, a belief that it is possible to be a better version of oneself. I’ve been very moved, for instance, by the practice of the metta prayer in vipassana meditation — the hours and hours that a person spends ‘watching’ their breath, their thoughts, every last pulsation of their body, which would seem to be the height of self-indulgence, except that that the session concludes ultimately (when one is ready for it) in radiating compassion outwards. In the practice it’s understood that this is not to be done lightly — that energy directed out into the world tends to be counter-productive if one has not worked diligently on oneself first; and so an activity that seems so solitary, so inward-focused, is intended to be fundamentally social.

I’m not sure that Lasch, at least in his apoplectic, apocalyptic writing of the 1970s, was interested in solutions. (Solutions being beneath the pay grade of a prophet.) But I had kind of a stray thought that — more than the metta meditation in vipassana — may be along the lines of what Lasch had in mind for how to internally orient oneself in opposition to ‘the narcissist society.’ The thought had to do with the first season of The Young Pope and the moment in which the Jude Law character, something of an arch-conservative, declares, “The past is a treasure house with all sorts of things inside. The present is a narrow slit with room for only one pair of eyes. My eyes.” In a sense, the present itself is embedded in narcissism — subject always to the dictates of power. To have a stable sense of identity, an inner fortitude, it’s necessary to delve deeply into the past. In many cultures around the world, this is done through some form of ancestor-worship, some proactive preservation of cultural heritage. In the future-oriented, disposability-minded West, therapy and spirituality fill a gap. Therapy — the Freudian version, not the derivatives that Lasch took such issue with — is rooted in the past, in the belief that certain formative events determine the psyche; and that the proper understanding of them is the key to health. And spirituality, as silly as it can get, is basically a method of reconstructing mythology — of attempting to reach beyond the Western, Baconian tradition to something that is, in the magical phrase, a little more ‘holistic.’ What both therapy and spirituality aim at is — the same goal as in vipassana meditation — removal from attachments, distance from psychological blocks, inner freedom. There’s a beautiful glimpse of what this can look like over the course of the first season of The Young Pope — the titular character distancing himself from virtually all the obligations of his office, from all the usual compromises with his era, relying entirely on intuition and charisma. And something peculiar begins to happen — that, as far as I can tell, even took the show’s creators by surprise. An inner freedom opens up around him. A visiting prime minister finds herself dancing to pop music in the halls of the Vatican. A sedentary priest finds the ability to live in the outside world. A cynical bureaucrat recovers his faith. Within the context of the show, all of this is a very delicate dance — the fine line between ‘healthy narcissism’ and the other kind — but that’s sort of where I think the antidote to society-wide narcissism is to be found, in healthy self-love, buoyed by the past and animated by spirit. It’s not really in a Charles Murray-esque return to the nuclear family and the white picket fence. As Lasch helpfully reminds about the ‘70s, all eras — not just ours! — are sucky in their own way. Narcissism is a very difficult, and virtually untreatable, energy. The way to deal with it has to do with boundaries and inner bulwarks, an understanding of what one’s own values really are — without getting pulled into some narcissistic whirlwind — and an ability to cultivate self-love while delicately, maturely realizing that the self is not all there is.

Sam Kahn writes Castalia.

Sam, I did read the full Lasch essay on NYRB—fascinating—and long. I'm particularly taken with your view of meditation and of knowing oneself to express compassion. That insight provides a powerful close to your essay. Maybe you're our new Christopher Lasch despite Josh's ghost reference on twitter :).

I admit it: I didn't know who Christopher Lasch was until you just told me. Interesting enough: I also wrote about narcissism this past week. Have you read this yet? https://ponytail.substack.com/p/jupiter-juno-io-teiresias-narcissus