1

On the plane to Hanoi earlier this year, I was visited by the dead. I know that may sound a little dramatic. What actually happened was I opened a book to read during my flight and a letter fell out. What made the matter a bit chilling to me was that the book was Seamus Heaney’s verse translation of Book VI of Virgil’s Aeneid, in which Aeneas visits the Underworld to visit a dead parent. And the letter that fell into my hands was actually one from my mother, who’d been dead for over a year at that time. To add another layer to this, Heaney’s translation was a posthumous publication (published in 2016, with the poet having died in 2013), giving it the slightly uncanny feel of a communication coming from another realm.

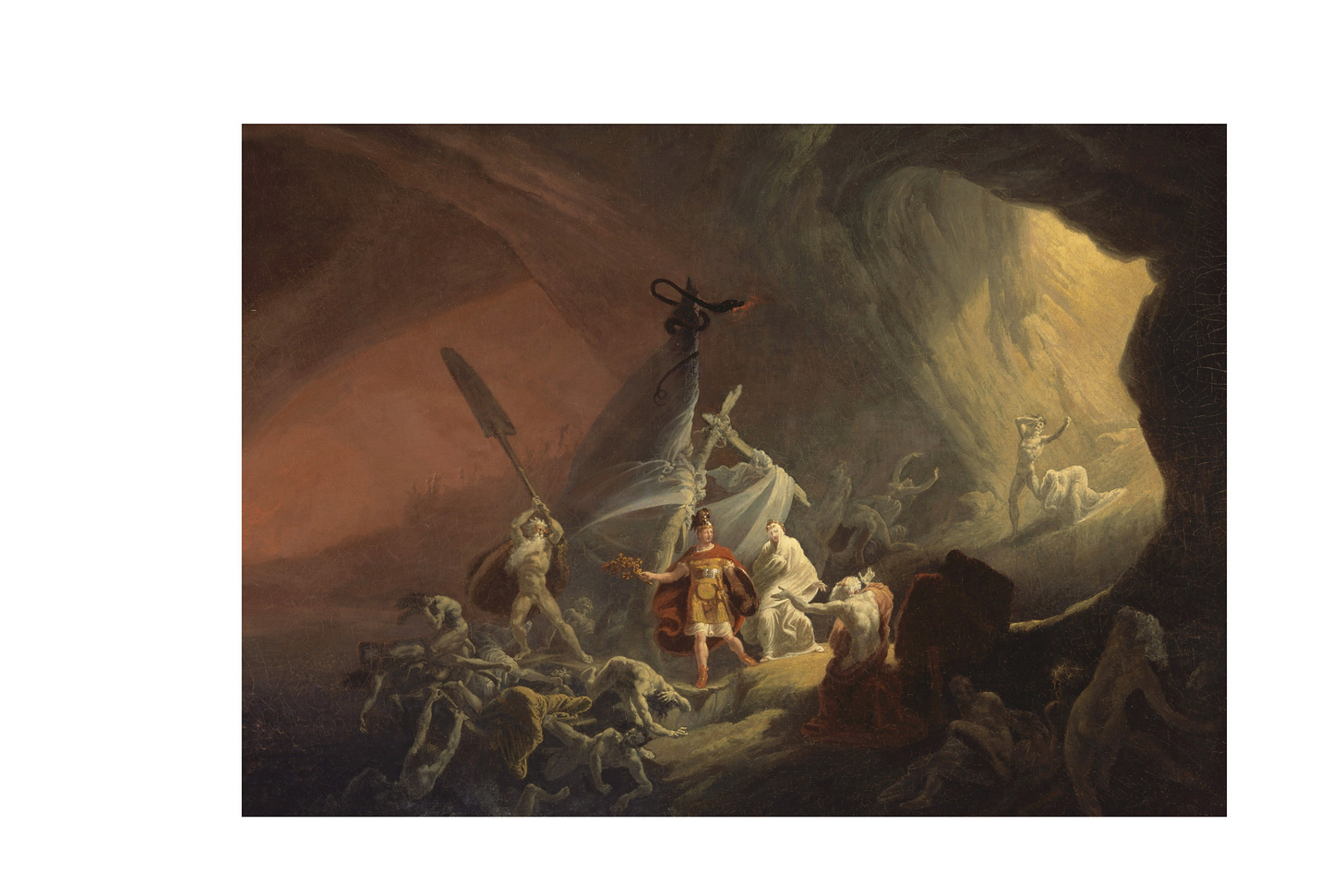

To the ancients, access to the world of the dead was usually a one-way trip. Though a lucky few (or, in the case of Hercules, a heroically strong individual) managed to enter and then make it back. Aeneas visits his dead father with the guidance of the Cumaean Sibyl, a prophetess. Book VI also explores some of Aeneas’ other unfinished business. In a long passage, the Sybil tells Aeneas that his loyal companion Misenus has drowned and lies unburied on a beach. To be denied burial rites was a dreadful fate for the ancients, and the Sybil, at length, makes it clear to Aeneas that he has to deal with this before he can visit his dead father.

The letter from my mother contained no dramatic news, no stunning insight from the past, no prophetic utterances, or any forgotten revelations. It was a regular letter from the days when email didn’t exist and international phone calls—I was usually in a different country from my mother—were prohibitively expensive. It did, however, mention “warm winds from Africa” (my parents had been on holiday in the Canaries), and this made me think of the “sudden gale” that had been the downfall of Aeneas’ helmsman Palinurus “as he held course/From Africa.”

According to the editors of the published translation, Heaney left an unfinished note, perhaps a draft of an afterword. In it, he describes one of the richest aspects of Book VI as the pathos of encounters of “the living Aeneas with his familiar dead.” 1

Familiar dead. Those two words have reverberated in my mind since I came across them.

And so my mother’s letter heightened my interest in the theme of Book VI as I relished Heaney’s fluent, rich, and beautiful translation. But if there was some secret sign to glean, I realised I had no gift for the interpretation of occult clues. I had no prophetess to guide me. And though Aeneas makes frequent use of auguries to chart his way in life, I have no such skill.

The way to the Underworld for the Romans lay through Avernus, which is located in a volcanic part of southern Italy with a “fuming gorge.” Avernus means “without birds”. I thought of how my mother had loved to watch the birds in her garden during the last years of her life. With her loss fresh in my mind, thanks to this hidden letter, I felt I, too, was now on a journey without birds.

2.

After we touched down in Hanoi, I found myself finally reaching the immigration counter after waiting two and a half hours. Watching it then take 90 seconds to let me into the country, I couldn’t help feeling that Charon, the ferryman to the Underworld, was also speaking to me when he says to Aeneas, “You, whoever you are... stop there.” We were all a little like the unburied dead in the poem, approaching the river Acheron to cross into the Underworld but unable to do so until buried:

Their doom instead to wander

And haunt about the banks for a hundred years.

But instead of burial, all we needed was a passport stamp, and so after my brief moment of nervous smiling through the Perspex screen at the weary immigration official, I was free and, luggage in hand, making my way to a vehicle that would take me to my hotel. On the way, I craned my neck to catch a better sight of the Long Bien Bridge as we crossed it. It reminded me of a bridge I’d seen in Cairo, but this one was heavily bombed during the Vietnam War (known locally as the “Resistance War against America” or simply “American War").

As I stepped into the busy hotel, I picked up the sound of chattering American accents. And judging from their ages — about 15 to 20 years older than me, on average — they might have been war veterans and their partners.

Fresh from my reading of Book VI of the Aeneid and its obsession with burial rites, I found myself wondering about the unburied war dead in Vietnam. It seems 1,600 Americans are still unaccounted for from the Vietnam War, though joint Vietnamese-American action to search for American MIAs has resulted in over 1,000 Americans being repatriated and identified. The numbers are much greater on the Vietnamese side, of course, with the remains of 180,000 fallen soldiers not yet recovered. Regardless of their allegiances while alive, the unburied dead lie where they fell all over the country—the mourned and the unmourned, the familiar and the unfamiliar.

3

Later that night in my hotel room, my mind went back to the start of 2020, when I was living in Hong Kong.

My family in the UK told me via WhatsApp that my father had been hospitalised. That had happened before, so I was worried, but not overly alarmed. Days later, when more messages revealed that he was not getting any better, I began to see such communication as some kind of sinister oracle—not just a bringer of bad news but an ill omen in itself. After 24 hours more of consulting with my family via this electronic Sybyl, I took a plane to England to visit my father. After I landed, I switched on my phone and found several missed calls from my family. I knew what that must mean. I was too late. I later found out that my father had died when I was somewhere over eastern Europe.

The day after I arrived, I went with one of my brothers to see my father’s body in the hospital mortuary, my first encounter with a dead human.

In Book VI of the Aeneid, when the dead Anchises sees his son Aeneas arrive from the world of the living to see him, he cries excitedly:

At last! Are you here at last?

In the sterile quiet of the mortuary, there was, of course, no such greeting for me. Just a body on a rack, one amongst many. But here amongst the gleaming metal surfaces, my father, who’d always had a strong presence while alive, overwhelmed me with his silence. It turns out he had a strong absence, too.

When Anchises greeted his son, Aeneas, he also told him that he had feared for him during his time in Carthage with Queen Dido: “I was afraid that Africa/Might be your undoing.” I don’t know whether my father had thought the same while I was in Egypt, which I’d left about 20 months before he died. But now there was no way to find out.

Within days, the gods of bureaucracy were propitiated. I presented the necessary documents to a kind, efficient woman at Torbay Council (she was no Sibyl), and she assuaged the mute computer deity on her desk enough to make it issue the death certificate—all while I was sitting, dazed and still jet-lagged, in her office. The burial rites were organised according to the laws and customs of England. In short, we held a simple ceremony to celebrate his life at the local crematorium and came away with his ashes.

The day I planned to fly back to Hong Kong was one of very heavy rain.2 With all the force of one of Virgil’s epic similes, by the time I had boarded a train to the airport, the River Exe had burst its banks. My train was stopped at Exeter, where the worst flooding occurred, and we were told to take a bus to Taunton, further up the line, to pick up a train from there.

Outside Exeter’s St Davids Station, the forecourt was filled with chaos. As the rain continued to pour down, stranded travellers seemed to grow in their panic. At one point, a bus left a huge queue of frustrated passengers behind with no information about when the next one might arrive. There was no electronic screen with calming information. Just a rattled, overwhelmed driver shouting to the stranded passengers that his bus was full, it was time to leave, and there would be another bus "later.”

*

Heaney had long been fascinated by Book VI of the Aeneid, and in the final collection of his own poetry, immediately before this epic translation, he wrote an autobiographical sequence of twelve sections called “Route 110.” In it, Heaney plotted moments in his life against episodes from Book VI.

In the third sequence, Heaney depicts the bus inspector organising the passengers into the right bus by using the route numbers—110 was the one Heaney used to take. It’s based on the scene in book VI where Charon, the ferryman, is in charge of deciding who gets to cross the river Styx to their destination in the Underworld.

There they stood, those souls,

Begging to be the first allowed across 3

*

As I gazed at the scene outside the station, I knew I was witnessing an unsurprising failure in the management of a UK rail company. There was nobody in charge. But I had a plane to catch and a border to cross before it closed indefinitely. I couldn’t help but wonder, “Where was my Charon?”

I spied him across the rain-swept station forecourt. A youngish man slumped over the wheel of a pale blue salon car marked "taxi”. With my bags in hand, I rushed through the deep puddles of water that had formed outside the station. The fee I negotiated—if you can really “negotiate” with a look of desperation on your face—was almost as swollen as the nearby river. But the driver, whom I took for East European based on his accent, was friendly enough. And almost immediately, we were off. It was here, as I drove away from my fellow scurrying travellers, that I recalled that my father had driven taxis for his father in his teens. I’m sure he never had a passenger as grateful as I was to be safely in that cab and underway.

4

In his preface to Book VI of the Aeneid, Heaney writes of his Latin teacher at school and his experience studying the Aeneid. He studied Book IX, but the teacher often expressed the wish it had been Book VI, whetting the future poet’s appetite for a text he would translate so magnificently at the end of his career.

I also studied the Aeneid at school, about twenty years later than Heaney. My set text was from Book II, which deals with the fall of Troy. I won’t deny that there were some exquisitely boring moments in Latin classes, as the afternoon lapsed rather than passed and the classroom echoed to the dull declension of nouns:

Filius

Filii

Filio...4

But there were also memorable passages that earned our grudging teenage attention, such as the description of Priam’s death, slain just after his son and dragged through his son’s blood by the son of Achilles, Pyrrhus. There are so many sons and fathers in the poem, and the slaughter of a number of them preceded the end of Troy and formed the background to Priam and the city’s grim fate:

A once mighty body lies on the shore, the head

shorn from its shoulders, a corpse without a name.

Our teacher, who seemed as ancient as Troy to us, had a nickname, Ghosty. I remember that when he retired, he quipped to the assembled school with typical dry wit about his departure from our school.

“Ghosty goes west,” he said.

5

On the plane back from Hanoi to Tokyo, I chose what I thought was very different reading material: Banana Yoshimoto’s 1987 novella, Moonlight Shadow. However, I soon found that in this story, the narrator sees her dead boyfriend as a ghost on the other side of the river: “The border between my country and Hitoshi’s—that’s what the river was to me.”

I smiled at the coincidental recurrence of the image of the river separating the dead from the living and of the dialogue with ghosts.

I thought again of my father’s body laid out in the mortuary, proud as Anchises but silent to his mourning son.

I thought of the letter from my mother that had nestled within the pages of Book VI and found its own echo there.

I thought once more of the buried and the unburied lying on so many distant shores.

And above all, I thought of the need we feel to encounter, one last time, our own familiar dead.

Jeffrey Streeter writes

Note:

was a developmental editor on this essay.Aeneid Book VI, by Virgil, translated by Seamus Heaney, Faber, 2016. P. 51

Delay wasn’t an option. I was pretty sure that Hong Kong was about to close its borders to visitors from the UK due to the rapidly emerging pandemic. And I was right. They closed two days after I got back.

Aeneid, Book VI, p. 18

A lovely braided essay. So many poignant echoes of the text with your own memories, and I agree with others who have responded to that arresting phrase, "the familiar dead." A fine example of defamiliarization!

My daughter is fond of Greek mythology, and I sometimes read to her from Edith Hamilton at bedtime. Last night we were reading the story of Atalanta, and I read Hamilton's note on the text, where she claims that Apollonius offered by far the most reliable portrait of Atalanta, especially compared to Ovid, who was prone to exaggeration. It reminded me that the timeless appeal of the classical tradition, which was once the very trunk of the humanities tree, lies in its power of suggestion. We now demand that literature represent our identities to the letter, but everyone studying Greek texts is dealing with fragments, translations, partial truths that the translator, like Hamilton, must synthesize into a retelling. As you do so wonderfully here.

Which is to say that the familiar dead aren't waiting for us fully formed. We have to fan them from their ashes, which smolder on in us.

This is a beautiful essay, Jeffrey. It is as deftly woven as a fine silk veil and evocative as twilight. You summon your familiar dead, and we recognize them as our own. You ferry us from Africa to Hanoi to Hong Kong to England; bury the dead and resurrect an old schoolmaster; hijack a taxi, and get home just before they lock you out. What a journey. Thank you for this extraordinary, haunting story.