Grapes, Grit, and Grandeur: My Year with John Steinbeck

Thoughts on reading Steinbeck's complete works over the course of one year

Throughout the years, I have relied on books to help me explore and examine the complex thoughts and deep emotions that make up my inner life. Writers transform the sublime into words, allowing us to discover hidden depths in stories and ourselves. The best writers transport us in time and place so we become a part of the story, embodying the things we discover and making them a part of us.

Each fall, I sit down to plan out my reading for the following year. This is a special day as I think critically about which books to read. Time is finite, and so are the books in one's life. I look carefully through my unread shelves and the list of books I keep close at hand. Where will the new year take me? What will I learn about the world and myself? Who will I become?

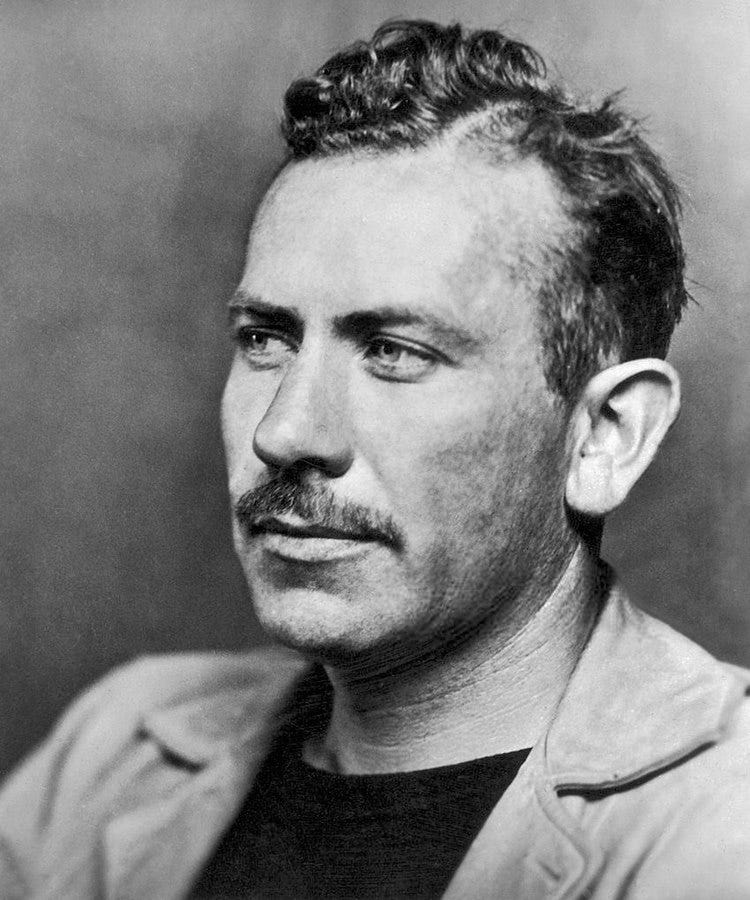

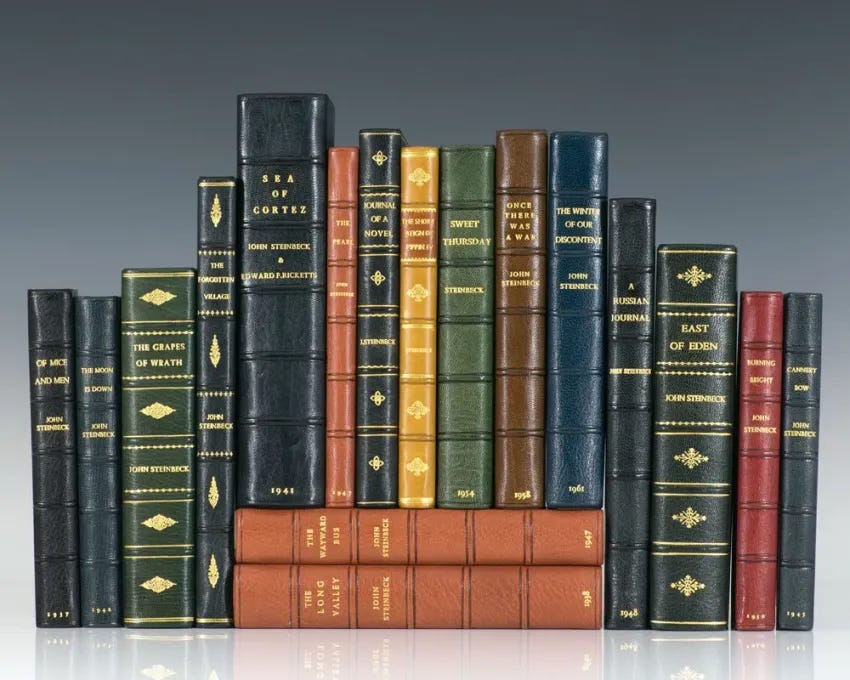

This past year, I embarked on a project to read John Steinbeck's complete works in publication order. I love East of Eden and was interested in discovering how Steinbeck developed as a writer throughout his career. I wondered if consistent themes were present in his works and if his early books stood up to his later masterpieces. I was also curious about the man himself. What drove him to write in a manner so seldom seen today? What was his inner life like?

I had no preconceived notions of what I would learn or if I would even enjoy his other writing in the same particular way East of Eden had moved me. Having completed this journey through his books, including reading three biographies and a book of his letters, I have greater insight into the man who felt so passionately about his work. He put his heart on paper for the world to read. Some of his works resonated with me. Others could have been more impactful. Taken as a whole, they provide a picture of the author and America in the early to mid-20th century. The America Steinbeck knew was already receding when he died and is almost unrecognizable today. However, his work lives on as a lasting piece of the canon of American literature.

John Ernst Steinbeck was born in 1902 in Salinas, California, into a comfortable, middle-class home, the only son of John Sr. and Olive. He was spoiled by his older sisters, Esther and Beth, but was closest with his younger sister, Mary. Other children liked him but considered him a loner who was friendly but serious, often preoccupied with his thoughts. In school, he was shy and indifferent. He did not care much for academics other than English, which he loved. His favorite author was Sir Thomas Malory, who wrote Le Morte d’Arthur. His fascination with King Arthur would influence his storytelling throughout his life.

Steinbeck loved dogs, enjoyed being outdoors, and developed a love for growing things. He was fascinated by the mountains surrounding the valley and regularly ventured out to explore, often with Mary in tow. They loved riding a pony named Jill, a gift for his fourth birthday, which inspired his book, The Red Pony.

“Good writing depends on the writer having something to say.” - Edith Mirrielees

Steinbeck chose Stanford for college, although he was uninterested in any class unrelated to writing. Edith Mirrielees, a professor of English, was a central figure in Steinbeck’s education. He loved her short-story class so much that he took it twice, and while her impact on him was significant, Steinbeck couldn’t be convinced to stay in school. Dropping out, he moved to New York City, working odd jobs, including a short stint as a reporter.

Returning to California, he became the caretaker of a remote lake property. The solitude was needed to commit himself to writing. Lacking confidence as a writer, a trait that would remain even after he had found fame, he persisted and completed his first manuscript. Steinbeck felt drained after finishing this work and wondered if he would ever find the “Sharp agony of words…” compelling him to write again. Like many writers, he believed writing did not make one a writer. Instead, true writers did so because they could not help themselves; it was something ingrained within. He was frustrated with his inability to find a publisher and became sullen and self-absorbed. For a short time, he considered moving to Europe, where many of the best writers of the day were living and working.

His first book was published in August 1929, a few months before the stock market crash. Steinbeck had been dating a woman named Carol, and in January 1930, they were married. After a short stint in Los Angeles, they made their home at the Steinbeck vacation house in Pacific Grove near Monterey. While there, a life-long friendship began when Steinbeck met Ed Ricketts. Ricketts owned a research laboratory on the waterfront in an area known as Cannery Row. This lab became the gathering place for the young, artistic crowd, a bohemian group of friends who held wild parties, including an eclectic mix of drinking, cheap eats, strip poker, and deep conversations.

Steinbeck was working on several projects during the early 1930s. When his mother became ill, he remained at her bedside for months, taking care of her. He used this time of relative solitude to think and write. After his mother died in 1934, Steinbeck’s career took off when several works were accepted for publication in rapid succession. His father then died in 1935, leaving him some money. Combined with the success of his recent books, he could focus on writing. However, as he grew in fame and fortune, he constantly struggled to manage his finances. The more money he made, the more he spent.

The 1929 stock market crash brought thousands of people west. Steinbeck had a front-row seat to the mass of migrant workers following the harvest in California’s agricultural valley. Referred to as “Okies,” regardless of their state of origin, these desperate individuals would find a place in Steinbeck’s heart. He had struggled to see anyone suffer, a trait that remained consistent throughout his life. The plight of those seeking employment, food, and hope would inspire some of his greatest works.

Steinbeck’s career took off after he published two successful novels, Of Mice & Men and The Grapes of Wrath. However, his personal life was in shambles. When he and Carol separated, he moved to New York City with his girlfriend, Gwyn. He and Gwyn would marry and have two sons, Thomas and John. This marriage lasted barely five years, and the divorce led to severe depression. In 1950, he married Elayne, with whom he would remain until his death.

The second half of Steinbeck’s career was filled with success and relative stability. East of Eden, often considered his magnum opus, was published in 1952. A decade later, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, becoming a living icon of the literary world.

“Try to understand men, if you understand each other you will be kind to each other. Knowing a man well never leads to hate and nearly always leads to love.” - John Steinbeck

This brief biographical sketch barely touches the surface of a deep and complicated individual. A deeper examination such as the one I undertook this past year allows for a fuller understanding of how his life influenced his writing. The themes of his writing often stemmed from personal experience or observation.

Since childhood, Steinbeck had adventure stories filling his imagination. The Tales of King Arthur left a lasting impression, and he longed to share the exploits rolling around in his head. Isolated in a remote mountain cabin, he put pen to paper, writing his first manuscript, an adventure tale loosely based on the life and times of Henry Morgan, pirate and buccaneer. Correlations exist between this story and Steinbeck’s life. His father had made almost nothing of himself but supported his son’s dreams, as Henry Morgan’s father did. In what seems prescient looking back, Steinbeck continually searched for love and companionship that eluded him. His life was filled with success, fortune, friends, and women, but he struggled to make any of it last.

Throughout his life, the Salinas Valley remained central to who he was. The valley called to him. It demanded the work of his pen. As he explored themes of physical, mental, and spiritual journeys, the vast agricultural mecca of Salinas Valley was a common destination. Steinbeck was compelled to return home time and again in his life, writing, and death.

Early in his career, he developed the Phalanx theme – the idea that a group operates like a single biological unit. In writing about Steinbeck’s body of work, Critic Edmund Wilson remarked that “biological realism was Steinbeck’s ‘natural habit of mind’ and it translated in his books to an ‘irreducible faith in life’ which Wilson admired.” Ecology, biology, and the interconnectedness of the human condition with these forces all provided a framework for Steinbeck that influenced his works.

In a review of Steinbeck’s writing, literary scholar James Gray wrote that his anger set him apart from all other writers. “All his work steams with indignation at injustice, with contempt for false piety, with scorn for the cunning and self-righteousness of an economic system that encourages exploitation, greed, and brutality.” Steinbeck’s inability to tolerate suffering in others was a theme that continued from childhood onward.

The best testimony of his philosophy comes in his voice as narrator, given to us within his masterpiece, East of Eden, speaking to the importance of freedom of thought.

“And I believe this: that the free, exploring mind of the individual human is the most valuable thing in the world. And this I would fight for: the freedom of the mind to take any direction it wishes, undirected. And this I must fight against: any idea, religion, or government which limits or destroys the individual. This is what I am and what I am about. I can understand why a system built on a pattern must try to destroy the free mind, for that is one thing which can by inspection destroy such a system. Surely I can understand this, and I hate it and I will fight against it to preserve the one thing that separates us from the uncreative beasts. If the glory can be killed, we are lost.”

Steinbeck continually draws attention to the inherent value of people, particularly those at the margins of society. He builds on his Phalanx philosophy, examining “group think” and how reactionary behavior impacts the individual who is powerless against the herd. Does an individual's dream have value? Do dreams give our lives meaning? What obstacles does society place in the path of the personal dream? These are all questions posed to us in the context of these stories.

While many of Steinbeck’s themes were outwardly focused, they reflected the man's complexity, deep thinking, and intense emotions. Writing was, for Steinbeck, the pathway to expressing himself on issues he believed strongly about, such as human dignity, social justice, ecology, the natural world, connectedness to the land, isolation, community, the heroic, the ordinary, moral ambiguity, and personal responsibility. Over and over again in his works, we see these ideas spring forth in his unique storytelling voice.

Steinbeck was a prolific writer, but his two most significant works are undisputed. The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden showcase his immense talent while drawing the reader into the critical themes of his work. These masterpieces are also excellent examples of place writing where the locations take on a life of their own and become characters in the story.

Everything Steinbeck had written before The Grapes of Wrath was a training ground for the ideas, philosophies, and themes that found life in this work. More than any other he ever wrote, this intensely human story took a stand on issues important in his day and throughout history. He passionately expounds on the plight of people experiencing poverty and the undeniable truth of human dignity. In a compelling portrait of the conflict between the powerful and powerless, Steinbeck shows how land-owning corporate farmers colluded with government agencies and law enforcement to exploit workers, exploiting their rights in the self-serving pursuit of riches. The writing evokes the harshness of the suffering caused by fellow human beings - man’s inhumanity towards man. Our sympathy for the Joads and all like them is aroused, yet their innate goodness and unbreakable pride inspire us. They overcome powerlessness through family, friendship, and community. Steinbeck’s Phalanx theory takes center stage when the migrants persevere, resist, and come together to form a unified whole.

Steinbeck viewed East of Eden, a sprawling and intense novel, as his most significant achievement. It was the story he always wanted to tell, with the idea germinating in his mind for over a decade. An ambitious work exploring the human condition, Steinbeck believed the book contained all he knew about good and evil. Set in California’s Salinas Valley and deeply rooted in the author's family history, it serves as a broader allegory for the human condition. The novel follows two interweaving storylines, depicting the fortunes of two families, the Trasks and the Hamiltons, from the Civil War to World War I. It explores themes of good and evil, sibling rivalry, and inherited sin. Steinbeck wrote East of Eden as a modern reimagining of the fall from grace, examining humanity's free will and the possibility of redemption. The novel grapples with human complexity and reflects the truth that people are not wholly good or evil but rather nuanced and flawed. Throughout this story, Steinbeck uses the theme of transformative journeys to explore the physical, spiritual, and mental changes many characters undergo. These journeys are pivotal in shaping their identities, moral understanding, and relationships with others. The characters' transformations often reflect their inner struggles with good and evil, self-discovery, and the quest for redemption.

“Men do change, and change comes like a little wind that ruffles the curtains at dawn, and it comes like the stealthy perfume of wildflowers hidden in the grass.” - John Steinbeck

Steinbeck faced many personal struggles during his lifetime, many of them of his own making. Early in his career, Steinbeck struggled financially, working odd jobs while writing. He worked as a laborer, bricklayer, and fruit picker, gaining firsthand experience of the working-class life he would later depict. He faced periods of poverty, often relying on his parents for support while trying to establish himself as a writer. He experienced several turbulent relationships, marrying three times and enduring emotional challenges in each marriage. He had a complicated relationship with his sons, particularly later in life, as he struggled with balancing his work and personal life. His strained family life influenced his writing, where themes of disconnection and troubled relationships sometimes emerge.

Despite his later success, Steinbeck was often met with harsh criticism. Many critics felt his style was too direct or sentimental, and his focus on social issues made some uncomfortable. When The Grapes of Wrath was published in 1939, it was banned in some areas and denounced as socialist propaganda. Even his Nobel Prize win in 1962 was met with skepticism, with some critics questioning if he deserved such an honor. Steinbeck grappled with this criticism, expressing frustration that he was often misunderstood or undervalued. He was not a fan of critics and complained about them regardless of whether they liked his work or not. At times, he referred to them as “lice and bewildered bastards.”

Though celebrated for his contributions to American literature, Steinbeck often doubted his abilities. He was intensely self-critical, frequently revising his work and agonizing over whether he was doing justice to the stories he wanted to tell. This insecurity was particularly evident as he worked on East of Eden, which he saw as his magnum opus. He questioned whether he could live up to his high expectations and often feared that his best work was behind him. At the same time, Steinbeck yearned for critical recognition and a literary reputation matching peers like Hemingway and Faulkner. Despite his popularity with readers, he often felt he wasn’t taken seriously by the literary establishment. This drove him to experiment with different forms, such as nonfiction in Travels with Charley and adaptation with The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights, in a quest for acceptance and acknowledgment.

These struggles reveal Steinbeck as someone who was not only sensitive to social issues but also deeply reflective and committed to his craft, even when it took a toll on his personal life and health. His resilience in the face of these obstacles added a deeper authenticity to his portrayals of characters struggling to survive and find meaning in their lives.

“No man really knows about other human beings. The best he can do is to suppose that they are like himself.” - John Steinbeck

Steinbeck is celebrated for his focus on the lives of marginalized people, particularly workers and the poor. His novels give voice to those struggling within the socioeconomic turmoil of his time. His characters' resilience, humanity, and hardships resonated powerfully with readers during the Great Depression and still resonate today. Because of this, Steinbeck is often seen as a champion of social justice, and his works have contributed to discussions on human rights and dignity. His work also explores moral ambiguity. His interest in human flaws and his refusal to oversimplify morality add depth to his stories. This complexity has given him a reputation as a serious, probing novelist who tackles universal human issues, making him a staple in American literature.

Some critics argue that Steinbeck’s writing can be overly sentimental or moralizing, particularly in works that deal with clear social issues. They contend that he sometimes sacrifices subtlety for impact. However, his straightforward style and his willingness to take a stance are also part of what endears him to many readers. Steinbeck’s style has been both praised and criticized. He’s known for his descriptive prose, particularly in his portrayals of the Salinas Valley. Still, some critics have found his language and structure too plain or unrefined compared to contemporaries like William Faulkner or Ernest Hemingway. Despite this, his accessible, direct style has kept his works popular across generations.

Steinbeck’s politics were sometimes polarizing. His sympathy for workers and critiques of capitalism led some to label him a socialist, and his works were occasionally banned or criticized for their perceived radicalism. This controversy only grew when he won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1962, with some critics feeling his works didn’t measure up to those of other laureates. Steinbeck’s supporters, however, saw the prize as a long-overdue recognition of his ability to capture the spirit of America’s working class.

Despite the critiques, Steinbeck’s novels have left an indelible mark on American literature. His focus on empathy, social justice, and humanity’s connection to the land continues to inspire readers and writers alike. His works have retained their relevance, addressing issues of inequality, environmental stewardship, and the resilience of the human spirit—topics still widely discussed today. Ultimately, Steinbeck’s reputation balances between admiration for his social conscience and accessible storytelling and occasional critique of his stylistic simplicity and moral directness. His work remains powerful, memorable, and profoundly influential, an enduring portrait of the American experience.

Steinbeck died in December 1968 in New York City from congestive heart failure. His ashes were interred at the family gravesite in Salinas, California, next to his parents and grandparents. In a final missive to his doctor as he neared death, Steinbeck said he would not survive this life and that when he died, that was the end; nothing else remained. Fortunately for us, he was wrong. His spirit remains a vital part of our culture through the ongoing influence of his literary works.

“It's so much darker when a light goes out than it would have been if it had never shone.” - John Steinbeck, The Winter of Our Discontent

Some questions to consider as you reflect on Steinbeck’s body of work:

How do Steinbeck’s characters reflect or challenge your understanding of resilience?

How does Steinbeck depict isolation and loneliness, and how do these experiences affect his characters?

How does Steinbeck portray moral ambiguity? Are there characters whose actions seem both justified and problematic?

Matthew Long writes Beyond the Bookshelf.