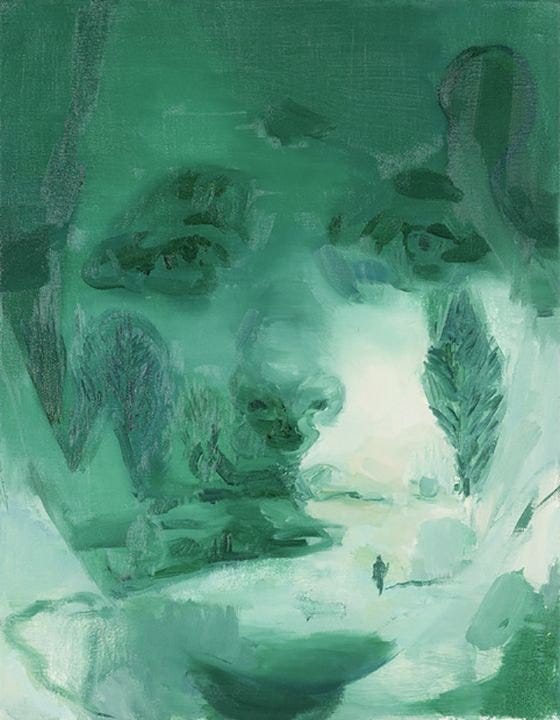

This is how your pain manifests.

I am 13, standing in front of an x-ray machine, drinking a chalky liquid filled with Barium. I’m doing this so they can look for problems in my upper digestive tract. When the results come back, my family doctor tells us nothing is wrong with me, despite the pain I feel after nearly every meal.

A few months later is a motility test. This involves putting a catheter the size of a spaghetti noodle up my nose, down my esophagus, and into my stomach while I take small sips of water.

Finally, after years of misdiagnoses, prescriptions that cause more pain, and tests that turn up nothing, I find myself undergoing an endoscopy. This time, a massive tube with a camera on its end is inserted down my throat, through my esophagus, and into my stomach and duodenum.

Lying on the examination bed in the sterile room makes me think of the sick bay in Star Trek. Over the doctor’s shoulder is a screen that displays the insides of my digestive tract, which looks to be a wormy, pink mess. The doctor smiles. “Beautiful! Beautiful!” he exclaims, as though we’re at photoshoot, while I gag away before him.

It has to be worth it. This doctor is the top of the mountain, the end of the road. If he can’t figure out what the matter is with me, no one can. And so I try not to react to the strange bedside manner, not to twitch uncomfortably, not to vomit bile on his table.

In the consultation room afterward, I sit as demurely as a I can, hoping to regain some dignity. “There’s nothing wrong,” he says. “Are you a people pleaser?” and I nod, flooded with shame, disappointed at one more thing I shouldn’t be.

“You put this stress on yourself. Try to do yoga. Or pray. You look like you pray.” He pauses for a moment before finishing with a flourish. “It’s all in your head”.

At the time, it feels like a cop-out, like the man with the many degrees not doing his job. But what do you tell someone who complains of constant pain and discomfort when you can’t find a physical reason for their suffering? How else do you explain these outward manifestations of inner agony?

“Do you feel anxious?” my family doctor asks me years later. I’m sitting in her clinic, hands in my lap like a scolded child, trying to understand why my blood pressure is so high that she’s forbidden me from strenuous exercise. Just until we get to the bottom of things.

No! I don’t just say it. I declare it. I’m not anxious, I’m not anything that can be mistaken for a mental illness.

But over the next few weeks — as I go to test after test, sit in brightly lit waiting rooms, extend my arm to draw the blood and take measurements and fill out forms — I remember.

My heart pounding in my chest as though a furious prisoner.

My stomach clenching and twisting.

The inability to eat for days before a test, a presentation, a hard conversation with a friend or a sister or a parent.

The panic that overtook me for 48 hours in the 8th grade, at the thought of my mother seeing my score of 28 out of 31 on a math test1.

My whole body, vibrating against my bed when I should be asleep. A shiver that can’t be stilled with the piles of blankets I’ve burrowed beneath. The shaking so severe I think I might float off the bed and out the window.

Once I finally accept it, I wear my anxiety like a badge, if not of honour, than of recognition. I allow it to subsume me, become my entire being, as though to compensate for all the years I forced it to a back corner of my self where no one would see it.

I am Noha, and I am anxious. For a time, I introduce myself as this person, not realizing how I let the anxiety get comfortable, settle in, take the best seat on the couch, grab snacks. Get bigger and bigger until it is a balloon, choking me from the inside out. Still, I read post after post about stress and anxiety and the end of the world on Twitter as I doom-scroll, pressing the little heart underneath, a declaration of my ardent agreement.

And then one day, I hear someone say the story you tell yourself about yourself is who you become.

And I look back at my anxiety, at the fact that it’s grown instead of diminishing. Realize that the relief I felt at recognition has been replaced with a constant presence, heavy and hovering. For years I have said I am Noha, and I am anxious. And that is true, but I am also grateful, also happy and silly and loving and fun, and I haven’t said these things in so long that my soul hasn’t heard them.

I try it. I say I am grateful. I am blessed. I am loving and I am loved. I am open to growth. I can learn to be calm.

At first, I hardly believe the words, but I repeat them. And repeat them. And repeat them again. With gaps of course. Of forgetting and crying and breaking down and vibrating and panicking. When the panic has passed, I say them again. I am grateful. I am blessed. I look up the names of God to do with gratitude, Shukr. God is Al-Shakur - The Appreciative. And I learn to appreciate. I uninstall the Twitter app on my phone, and notice my vibrations diminishing. There can still be memes, but now they are schmoopy and saccharine, filled with hope and possibility. I consider the benefits of embracing the corny and the optimistic, counter to my cynical outer shell though it is.

I come across a meme that says, you can eat the kale, drink the alkaline water, take the supplements, do pilates or hit the gym, but if you don’t deal with the the stuff going on in your heart and mind - you are still unhealthy.

I press the heart, a declaration of my ardent agreement.

writesWhenever I share this story, people assume my parents, specifically my mother, had impossibly high standards. But it wasn’t her, it was me. When I showed her the test, I was ready with my explanations for my low low score of 90% - I was used to getting 100%, plus the bonus question. But she just smiled, said her customary, “masha Allah habibty, you did so well”, and went back to cutting up the chicken she was prepping for dinner.

Noha, I am laughing at your ardent agreement and teary for the anxious girl with the report card all at once. I love the footnote about your mother. You’re right, I did go straight to suspicion of your parents, though as a parent I should know better. You tell this beautifully.

Beautiful writing Noha, as always. I heard Dr. Susan Davis make this distinction between, “I am (anxious)” and “ I FEEL (anxious)”. I think this distinction is incredibly helpful. “I am” suggests that your (anxiety) defines you. “I feel” puts the necessary distance between what you currently feel and your more permanent being. I would also add that in the Spanish language there is a distinction between a more permanent being (ser) and temporary being (estar). Hope this helps!